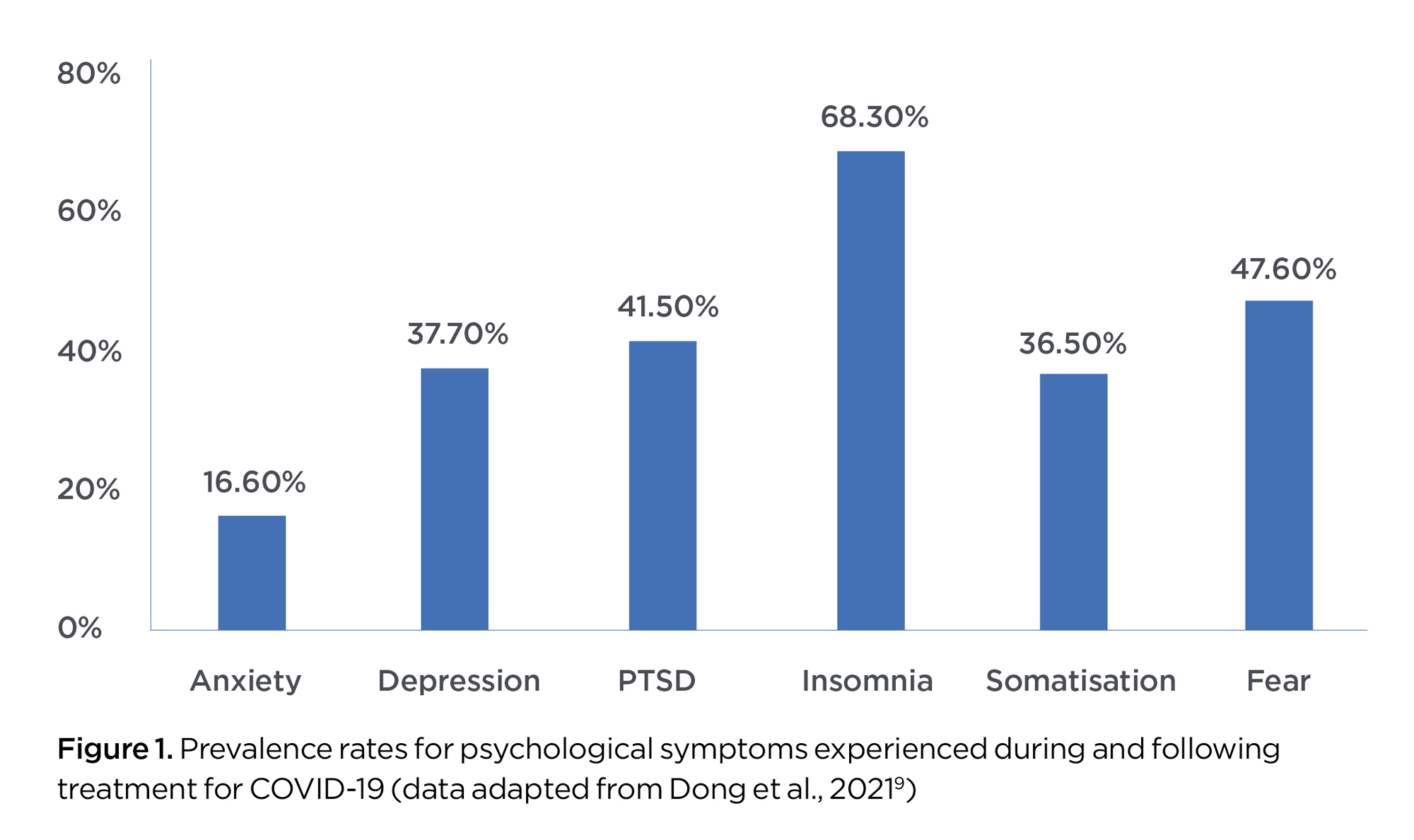

The COVID-19 pandemic has been long-term both in length and impact on the health of many Australians. Among the effects of long COVID are ongoing psychological needs. While close to 50% of people who have had COVID-19 may experience psychological distress during or following infection, and about one-third may experience prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, fewer than 14% have received follow-up psychological assistance. We need to talk about the symptoms of long COVID, along with risk factors and strategies for psychologists to use to help clients.

Psychological symptoms of COVID-19

A range of psychological symptoms may be experienced with COVID-19, including:

- fear of infecting others and/or survival1, 2

- the experience of stigma or negative treatment by others due to having COVID-193

- extreme loneliness and isolation2, 4

- increased stress and trauma responses4

- treatment-induced psychotic symptoms5, 6

- potential for substance withdrawal effects or re-traumatisation during treatment7.

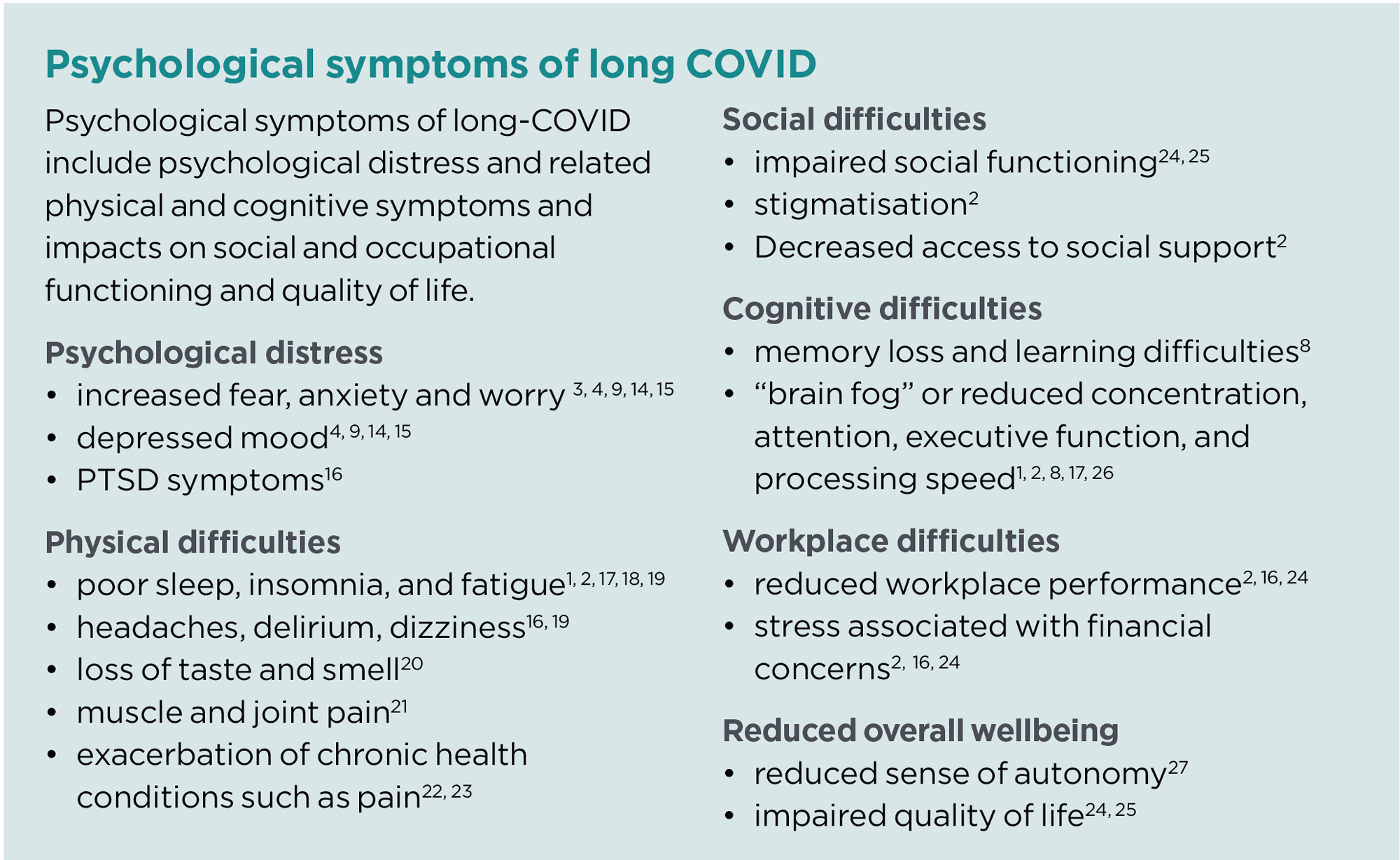

As more data becomes available, the true prevalence of these symptoms will be better understood. However, early results from meta-analyses suggest 35–46% of patients will experience psychological distress during or directly following treatment, with 17% to 22% of these individuals reporting moderate-to-severe distress2 and 67% of patients exhibiting one or more deficiencies across various cognitive assessments (e.g. working memory and processing speed)8. Figure 1 shows the prevalence rates for different psychological symptoms from one9 meta-analysis. Despite these findings, studies have reported that fewer than 14% of patients received follow-up psychological assistance10.

Long COVID, or post-COVID condition, refers to a range of physical, psychological and neurological symptoms shown to persist longer than four weeks11. The World Health Organization developed a clinical case definition of post-COVID conditions which states the symptoms last at least two months and cannot be explained by alternate diagnoses12.

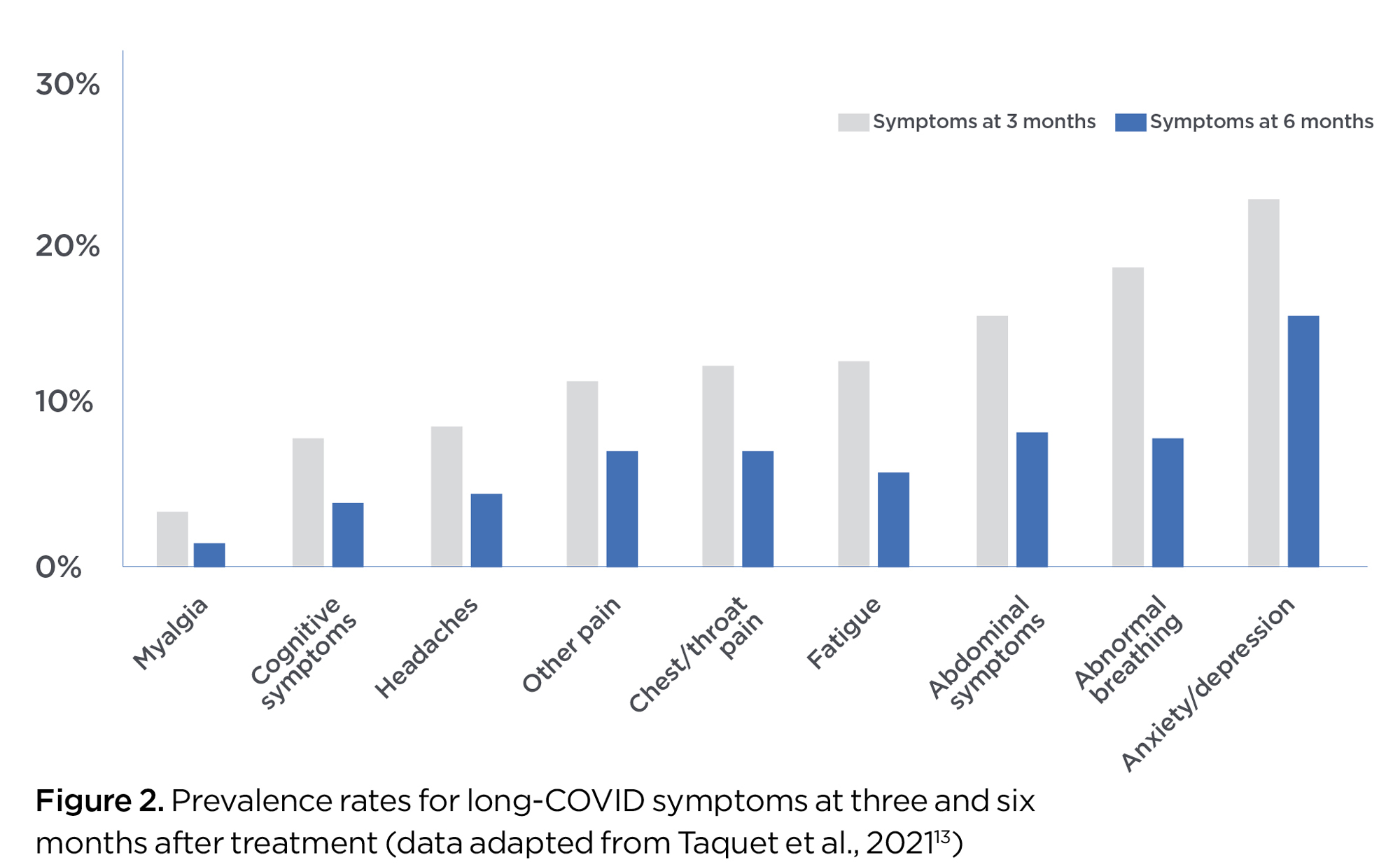

Psychological symptoms are one of a range of COVID-19 symptoms which may be long-lasting. Evidence from a large-scale analysis of medical records (collected from 273,000 COVID-19 survivors) suggests that of the persistent effects, psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression may be the most enduring (Figure 2)13.

Aggregating findings across multiple studies and different psychological outcomes, it is estimated that 38% of individuals will experience some form of long-term psychological distress (measured at three or more months post-treatment), with 18% of these exhibiting severe-to-moderate effects2.

Demand for psychological services

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, there has been an increased demand for psychological services. This is in part related to the psychological impact of COVID-19 infections as well as the impact of pandemic restrictions, such as lockdowns, on mental health.

In our own survey of more than 1400 APS members nationwide, 88% of psychologists reported increased demand for services. One in three (33%) of psychologists were unable to take new clients, whereas before the pandemic it was only 1 in 100 psychologists not taking new clients.

Medicare data indicates more than 21 million subsidised mental health sessions were conducted between March and September 2021, representing a 69% increase in service delivery from 2019-202028, 29. Lifeline has reported a 40% increase in service use compared to 201930. The World Health Organization suggests increased investment in services to avoid potential mental health crises31.

Risk factors for psychological effects

A range of risk factors have been found to be associated with increased prevalence of persistent psychological effects. Persistent physical symptoms of COVID-19 and identifying as female have been found to be associated with increased anxiety, depression and reduced concentration10,26 while younger patients have been found to be more likely to experience anxiety15. Previous history with mental health diagnoses and an absence of social support have also been related to more severe psychological responses9, 32, 33.

The intensity of treatment required (e.g. ICU admission) has been linked to heightened psychological and neurological symptoms,8, 9, 26 although an early analysis challenged this, finding no significant relationship between disease severity and anxious/depressive symptoms, suggesting even mild cases may potentially result in heightened long-term psychological distress20, 33.

Drawing on evidence from the previous SARS pandemic, self-perceptions of low disease impact and high-coping efficacy (i.e. positive primary and secondary appraisal) may be the strongest protective factors of psychological wellbeing34. Research has found that together these explained 39% of the individual differences observed across anxiety ratings, and 42% of differences on ratings of depressive symptoms34.

Although to our knowledge no studies have examined the added risks of Australia’s geographic dispersion, rural communities generally have limited access to medical treatment and support (compared to metropolitan areas)35. Furthermore, rural populations tend to be older, with higher incidence rates of COVID-19 risk factors such as renal and cardiovascular disease35, 36 whilst also exhibiting lower vaccine adoption37.

Increased access to specialist services, more vaccine availability, and expanded telehealth support are likely required given these additional risks for regional communities36, 37. Expanded telehealth access has been shown to improve cost-effectiveness as well as efficiency of healthcare provision in rural and remote settings38.

What can be done?

Psychologists have a critical role in providing support to patients following treatment for COVID-19 and in assisting them to adapt to and manage any long-term symptoms. Psychologists can also play a role in educating medical professionals on the potential post-treatment cognitive and emotional symptoms and the role of psychological treatments. Based on the feedback of psychologists from diverse areas of practice, there are several steps psychologists can follow to assist patients following medical/physical treatment for COVID-19.

Prior to discharge from hospital

- Monitor patients’ psychological health, wellbeing and functioning post-treatment, conducting regular follow-up assessments (especially for individuals who exhibit early symptoms of distress).

- Provide psychoeducation and information regarding potential post-treatment secondary effects and/or identify risk factors of subsequent psychological distress (i.e. increased risk of depression, anxiety, social isolation and/or neurological issues associated with recovery processes)9, 14,15, 39. Additionally, long-term effects or complications due to pre-existing health concerns (i.e. chronic liver, lung, kidney disease, or heart conditions) should be explored40.

- Discuss positive coping and cognitive reappraisal efforts33.

- Collaborate with patients and healthcare teams to develop reintegration plans, including scheduled follow-up appointments (especially with patients exhibiting early symptoms).

- Encourage patients to ask questions and discuss any concerns or worries prior to discharge39.

Post COVID-19-treatment follow-up

- Consider a biopsychosocial perspective to assessment and treatment, taking into account biological, neuropsychological, social and psychological factors that contribute to the long-term health condition41,42.

- A multidisciplinary approach to treatment is also recommended, including physical, psychological and psychiatric aspects of treatment21. For example, should there be symptoms such as fatigue, breathlessness and/or brain fog, these may need to be addressed by a medical practitioner alongside psychological treatment to ensure safe and effective client care21.

- Assess patients for potential symptoms of reduced cognitive functioning and psychological distress (i.e. depressive/anxious symptoms, fear, PTSD, fatigue/insomnia, cognitive functioning, disrupted daily routines and negative social impact or stigmatisation)9,14,15,39.

- Provide support and psychological treatment where appropriate (within a stepped care framework)43. Treatments such as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), Trauma Focused Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (TF-CBT), and Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) can be employed for patients suffering traumatic reactions or increased health anxiety and mood disorders39, 44, 45 although no improvements have been observed for fatigue symptoms46.

- Where daily routines, work or social functioning are impacted, explore graded return options and/or behavioural rehabilitation. Specifically, aspects of patients’ stress, fatigue, cognitive functioning and sleep management, and how these impact on individual functioning should be explored47.

- Broader use of behaviour change techniques, such as self-monitoring, problem solving and action planning, and techniques targeting health behaviours (e.g. diet, exercise, sleep, substance use) are also recommended42,48. The COVID-19 pandemic has had considerable impact on population behaviour and these behaviour changes are likely to impact on recovery from long COVID48.

- Refer patients experiencing prolonged or severe psychological distress to specialist treatment or trauma services where appropriate (particularly for enduring cognitive or neurological symptoms)20.

- Although prolonged symptoms are prevalent, not all patients experience these, and some may experience positive emotions such as a sense of gratitude, positive life changes or a willingness to help others39.

- Provide guidance on self-managing ongoing symptoms21, 42.

General community support

- Advocate for the provision of crisis support interventions, including counselling and other psychological services, to affected individuals4 with these processes supplemented with online access to psychological support2.

- Support awareness of the mental health aspects of the pandemic, including dissemination of psychological and psychoeducational services24, 49.

- Advocate for clear communications regarding COVID-19 specific information (i.e. rates of infection, vaccines and quarantine information), physical/mental health information2 and support for vaccine adoption.

- Encourage and advocate for increased access to social support, especially as individuals experiencing psychological distress may also be stigmatised within their support networks2.

- Support rural community access to mental health and medical support services36, 37.

Limitations and assumptions

Evidence is still emerging about the prevalence rates and risk factors which increase long-COVID symptomology. Early meta-analyses included studies from the initial phases of pandemic. These individual studies are likely to be characterised by heightened fear and uncertainty in the community, thus standard errors for fear ratings in meta-analysis may be skewed. It remains unclear when psychological distress symptoms may emerge, however it is currently assumed these emerge during/following acute stages. The risk and protective factors examined are not exhaustive and as more studies explore these effects more detailed information is likely to become available.

There remain unknown outcomes associated with different variants of the COVID-19 virus. However, the resource this article is based on will be periodically reviewed and updated as new evidence becomes available.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank and acknowledge the contributions made by the British Psychological Society, the American Psychological Association, the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, and input from the APS Colleges in developing the resource that this was adapted from.