Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed it is the only thing that ever has - Margaret Mead

Social protest movements are collective efforts to enact or prevent some form of social, political, economic or environmental change (Thompson et al., 2016). They are often initiated by those directly impacted by the issue, and then build to success through the engagement or approval of the majority of the population. They include traditional on-the-streets demonstrations, but can involve many other forms of activism such as hunger strikes and people chaining themselves to trees. Why do people do it? One answer to this question is – because it works!

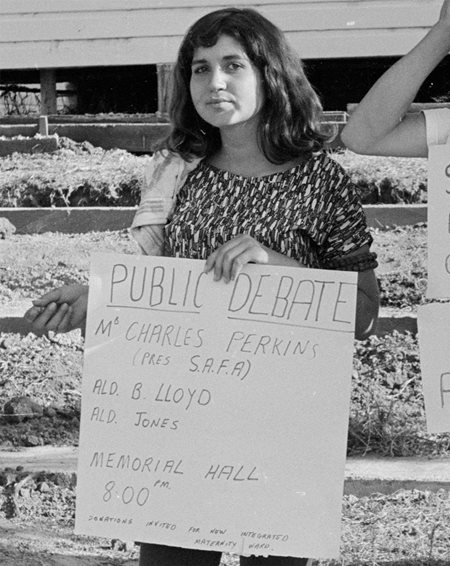

Protest movements have been instrumental in achieving major societal reforms. Among many examples are the women’s suffrage movement in the early 20th century resulting in women gaining the right to vote; the anti-apartheid movement led by Black South Africans from the 1960s to the 1990s which resulted in majority-rule; the Freedom Rides in the 1950s and 1960s in the US which advanced the rights of African Americans; the 1965 Freedom Ride in NSW (led by Charlie Perkins and his fellow students at the University of Sydney) which led to Aboriginal people being given the right to share public swimming pools and eventually becoming citizens; the Vietnam moratorium protests in the US and Australia which hastened the end of the Vietnam War; and the protests that led to the saving of the Franklin River in Tasmania.

Collective activism

Current examples of protest movements include the School Strikes for Climate, in which many millions of children and young people across the world participated, and Black Lives Matter, which was reignited by the horrendous death at police hands of George Floyd, and spread around the world, bringing stark attention to racism in many forms. Both these movements receive a lot of recognition currently and are already having an impact on policies and practices.

In the 21st century, social media has become the dominant platform for activism and socio-political change (Rotman et al., 2011), altering the nature and progression of social movements (Zhang et al., 2010). Social media has given visibility to social movements that may otherwise not have been seen – for example, the struggles of colonised people like West Papuans and the rights of minority groups like the LGTBIQ community.

Some research suggests that higher levels of activism on social networking sites (e.g., signing petitions) are associated with less conventional or higher-risk activism behaviour (Yankah et al., 2017). On the other hand, social media is an invaluable tool for information exchange amongst social activists, perhaps first demonstrated through the use of text messaging in the ‘People Power’ movement in the Philippines which overthrew President Marcos in the 1980s (Montiel, 2006).

Anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and protests outside Central Police Court, Liverpool St, Sydney, NSW. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

Protester with sign, from the ‘Student Action for Aborigines’ protest outside Moree Artesian Baths, February 1965 – The Tribune Image from the State Library of NSW

International Women’s Day March, 1965 from Bathurst St, Sydney NSW Image courtesy of the SEARCH Foundation, from the collections of the State Library of NSW

Who protests?

Even though the numbers involved in protests are sometimes in the millions, they still involve only a minority of the population. Why do some people but not all take an activist stance? Corning and Myers (2002) define an individual’s orientation toward engaging in social action as a “relatively stable, yet changeable orientation to engage in various collective, social-political, and problem-solving behaviors. These behaviors span a range from low risk, passive, and institutionalized acts to high-risk, active, and unconventional behaviors” (p. 703).

Historically, age has been one relevant factor, but is perhaps becoming less so. During the 20th century, protesters were typically young people of university age and often from educated backgrounds, but in the 21st century we have seen young people of secondary-school age and even younger become empowered to protest about issues that will impact seriously on them and on the world.

At the same time, social activism now occurs across the age spectrum, with groups like Grandmothers for Refugees (www.grandmothersforrefugees.com), the Knitting Nannas fighting against the use of fossil fuels (knitting-nannas.com) and Extinction Rebellion’s Grey Power groups for people over 50 working for action on the climate emergency (www.facebook.com/GreyPowerEarth/). Similarly, many voluntary groups of professionals with a predominantly middle-aged membership draw on their particular expertise to engage in social activism (e.g., Climate and Health Alliance www.caha.org.au for health professionals).

Factors that drive activism

Values are a salient factor in activism. For example, among young people, those with stronger ‘bigger than self’, or ‘self-transcending’ values like a belief in social justice, equality and environmental justice, and with a global perspective, appear more likely to be active on social issues (Sanson et al., 2019). In a study of 75 male clergy in Boston during the controversy over school desegregation, equality and freedom were the two values significantly correlated with social activism (Thomas, 1986).

Emotions are a strong factor in activism and are related to values, although the extent to which they actually drive engagement in protests is less clear (Stürmer & Simon, 2009). Awareness of injustice and inequality and moral indignation can lead to strong feelings of anger, which is often seen as the prototypical protest emotion, but contempt, shame, sympathy and outrage are also relatedto protest(van Stekelenburg, 2015). Deep feelings of grief have also been clear in recent protests relating to the climate crisis and to Black Lives Matter. Shared feelings or collective emotions within a group can enhance group identification, increase the magnitude and duration of emotions, and stimulate action (Goldenberg, et al., 2020).

Social connectedness and social norms are additional factors. In research conducted by members of Psychologists for Peace (then Psychologists for the Prevention of War) in the 1980s on the obstacles and motivators for taking action on the nuclear threat, two salient perceived obstacles to activism were “worry about what will other people think of me” and “I don’t have time/I have other obligations”, indicating the importance of activism being received as normative in one’s social group (Sanson et al., 1988). The more people identify with a group the more they are inclinedto protest onbehalf of that group, generating an inner obligation to behave as a ‘good’ group member (Klandermans, 1997; van Stekelenburg, 2015).

Activists also tend to have strong efficacy beliefs – both self-efficacy (my own ability to influence change) and collective efficacy (people together can instigate change), with collective efficacy being the stronger predictor (van Stekelenburg, 2015). They also tend to be oriented beyond themselves and their families to their community and the global environment (Sanson et al., 2019).

Anti Iraq War Demonstration In Melbourne, Photo by Regis Martin/Getty Images

Impact of protesting on the individual

Research on young people taking action on climate change indicates that it has considerable positive impacts. On the basis of a large body of research on youth participation, Hart et al. (2014) concluded, “Developing the skills and having opportunities to actively contribute to combating climate change can provide important psychological protection, helping young people to feel more in control, more hopeful and more resilient” (p. 93).

Anecdotal evidence from conversations with young people involved in the School Strikes for Climate, and self-reports from activists like Greta Thunberg, strongly indicate that taking action has helped them deal with their anxiety, grief and anger about the climate crisis – through action, they have channeled these feelings into determination, courage and optimism. They also describe the many skills and competencies they have developed through their activism – such as organisational skills, persistence, teamwork, leadership, conflict resolution, public speaking and learning to communicate effectively with the media, politicians and the police.

This is reinforced by psychologist and parenting expert Steve Biddulph (2019), who “was out among those young people.They struck me as the mature ones in the whole picture, their speeches were wonderful, their manner dignified and their demands… were moderate and thoughtful… The research says that when young people get involved in the things that worry them, then their mental health improves”.

Similarly, educationalist Nigel Coutts (2020) concluded, “A sense of agency can be the best defence against the potential to feel overwhelmed and disempowered by the scale of the [climate] crisis. Helping our students to realise and act upon their desire to make the world a better place, can result in powerful learning”(p. 20). As with many forms of anxiety, the best antidote to climate anxiety appears to be action (Sanson et al., 2019).

Psychologists for Peace have been interested in these issues since the height of the nuclear threat in the 1980s. More recently, members have worked with the APS to understand and address the obstacles to taking action on the climate crisis (see the Climate Change Empowerment Handbook and ACTIVATE model at bit.ly/3f4kQst).

This year, Psychologists for Peace have built on their pioneering work in developing a model of effective non-violent conflict resolution (the Wise Ways to Win model; Wertheim et al., 2006), the research on how communication needs to be carefully shaped for different audiences, and the research on the positive benefits for young people from working cooperatively in teams, and taking action on social issues they care deeply about to construct this year’s Youth for Peace Award.

We are aware that children and young people often feel there are few opportunities for them to get involved in meaningful ways on social issues (see bit.ly/2P0Vr8y) and this is particularly so during the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. We are therefore encouraging young people to work together on the Award in whatever ways are possible, including virtually. We aim to provide them with a fun, interesting and worthwhile project while building their sense of efficacy and hopefulness.

The first author can be contacted at [email protected]

About Psychologists for Peace

The Psychologists for Peace Interest Group is one of the oldest APS Interest Groups, having been established in 1984, initially as Psychologists for the Prevention of War, in response to the Cold War and threat of nuclear war. The group has been continuously active, with the focus of activities changing as the world and the issues it is facing have changed.

Among its many activities Psychologists for Peace have developed a model of non-violent conflict resolution which has been widely adopted, run various peace education projects, initiated four awards (children’s peace literature, peace art, peace research project and more recently Youth for Peace), and sold many thousands of wall calendars and posters on issues including conflict resolution, anger management, bullying and creating peaceful families.

Youth for Peace Award 2020

This new Award encourages innovative group projects that address current social issues around peace and conflict using psychological knowledge or strategies. The 2020 Award is focused on the climate crisis and aims to engage young people who we know are passionate about this issue.

The Award invites teams of young people aged 12–24 to work together cooperatively and, if necessary virtually, to develop a creative campaign or ‘pitch’ to promote messages about the need for climate action to influence the attitudes and/or behaviour of a specific audience.

A short video about the Award and creative ways to take part has been prepared (see vimeo.com/432689684) and by submitting a project for the Youth for Peace Award 2020 by 31 October, applicants could win a first prize of $1500 or one of two highly commended prizes of $750. Visit www.psychology.org.au/youthforpeace for more information.