The recent Black Lives Matter protests place us in a particular global moment, variously described as a crisis, the end of times. A moment for some that brings disbelief, outrage, indignation, lifting the veil and exposing massive and widening social inequalities across nations. But also a time that for many others, brings grief and a deep weariness, as this moment is but one thread tying together many painful histories. As individuals, organisations and institutions gesture toward solidarity through admirable public statements condemning systemic racism and vowing to tackle white supremacy, we must be careful to not place racism as a distant artefact, apart from us, or on the outside, somewhere else, or belonging to those who are racialised.

Persistence of racialised violence

Since the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, there have been 432 Aboriginal deaths in custody. Yet not a single person has been convicted (Allam et al., 2020). The evidence mounts and yet the reports keep coming.

In Australia, 96 per cent of CEOs, 98 per cent of Federal Government Ministry, 99 per cent of the heads of government departments and 97 per cent of university vice chancellors have Anglo-Celtic backgrounds. However modelling from the 2016 Census tells us that 24 per cent of Australians have non-European or Indigenous backgrounds (Australian Human Rights Commission [AHRC], 2018).

Another report found that 21 per cent of people agreed that African refugees increase crime (Blair et al., 2017); 60–77 per cent of African migrants have reported experiences of discrimination (Markus, 2016); another found 57 per cent of media pieces were characterised as negative when reporting on race, with a particular focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Africans and Muslims (All Together Now, 2019).

In a similar vein, in 2018 a motion to acknowledge anti-white racism framed in the white supremacist phrase “It’s OK to be White” was only narrowly defeated in the Australian senate (Karp, 2018).These statistics are not shocking. These statistics are not abnormal. These statistics are not new. They are the lived and everyday reality for communities that have been racialised, marginalised and subjected to symbolic and structural violence. These statistics tell a story of a nation founded on the dispossession of people whose institutions, stories and symbols are predicated on valuing some lives over others.

These are the facts of a nation built on an ideology of white supremacy that is maintained through a spectrum of violence. Violence that ranges from explicit acts against non-white individuals, to the more subtle cultural, ontological and epistemological violence that maintains majoritarian stories about non-white people and reproduces white ways of knowing, doing and being.

In effect, they represent a supremacy of ideas, or ‘cultural imperialism’, which involves “the universalisation of a dominant group’s experience and culture, and its establishment as the norm” (Young, 1990, p. 59). This imperialism also manifests epistemic injustice which “refers to those forms of unfair treatment that relate to issues of knowledge, understanding and participation in communicative practices” (Kidd et al., 2017, p. 1). It is the ways in which communities and people are wronged in their capacity as knowers and/or that they do not have a voice that is recognised (Kessi, 2017).

In combating these injustices, we must not assume reflexivity, or that a mere declaration of our complicity entails anti-racist practice. We must instead find ways to enact meaningful, lasting solidarities and anti-racist activisms, that seek to uproot the pernicious tendrils of our racist past and its continuities in the present. We write together, we are raced, gendered, able-bodied and differently positioned subjects by virtue of biographies and locations within the history of Australia’s racial formation.

We are engaged with these social locations crossing borders in the flesh into communities and symbolically through and across areas of research, teaching and community engagement activities that use concepts, and methodsfor critical reflexive praxis that disrupts structural and epistemic violence. Ultimately we are trying to imagine alternative futures and different lived realities for these communities and society, for without these, as de Sousa Santos (2014, p. 24) suggests, “the current state of affairs, however violent and morally repugnant, will not generate any impulse for strong or radical opposition and rebellion”.

Black lives, white lives and unsettling coloniality

This moment has many people searching for new ways of doing, being and coexisting in the world. Old questions have resurfaced probing at the deep foundations of Eurocentric knowledge about how we think about being human and the disastrous consequences of binaried, supremacist conceptions for those deemed below the line of the human. Grosfoguel (2016) draws on Frantz Fanon’s “line of the human”, which divides those people above the line as “recognised socially in their humanity as human beings and, thus, [enjoying] access to rights (human rights, civil rights, women’s rights, and/or labour rights), material resources, and social recognition to their subjectivities, identities, epistemologies and spiritualities” (p. 10).

Those below the line of the human are ‘The Nobodies’ as once described by Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano (1992).In his poem, he described the nobodies and nobodied, as those: “Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in the police blotter of the local paper. The nobodies, who are not worth the bullet that kills them” (p. 73). The Black Lives Movement in the USA and here in Australia (amongst other struggles globally) speaks to and seeks to redress this depressing reality.

For some a focus on Black Lives has been met with resistance invoking calls that ‘all lives matter’. Di Angelo (2011) has described these reactions using the notion of white fragility. For others, the current moment has generated feelings of uncertainty about what to do, how to do it and a fear that they will make mistakes, or that they will centre whiteness.

Yet, others have taken the opportunity to mobilise their anger, generated by the scenes of injustice beamed into their lives during lockdown via the news and social media. The current reality has meant that we can’t look away, we have to engage with the injustice that continues to constrain the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and other racialised people in Australia.

Australian contexts

Along with many others, we are deeply unsettled by this moment but we have also found hope in the long traditions of critical writing, scholarship and activism from the margins that point to ‘psychologies otherwise’. We don’t have to look very far to appreciate the struggle for survival and resistance against the effects of racialised and gendered domination.

Many have offered reading lists to help decentre, deconstruct and unlearn the social myths and forms of ignorance socialised through partial, distorted, and often omittedhistories in our schools, psychology programs and mainstream systems. In the Australian context, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, activists and academics across the country have led decolonising and anti-colonial work in Australia.

Engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and ways of knowing, doing and being, is central to the construction of psychologies that are diverse, inclusive, and are vital to unthinking how we have understood being human (see e.g., Dudgeon & Walker, 2015). These are calls for epistemic justice that are reverberating in many countries around the world.

In some of our own work and contexts, students, practitioners and researchers alike have called for and taken on the challenge of constructing applied psychologies in and outside the university to contribute to the empowerment and self-determination of the various communities who suffer the brunt of structural violence, poverty, racism, sexism, ableism and their interconnections that produce social suffering.

The parameters of these approaches are grounded in local contexts but connected through the global movements calling for liberation from various systems of oppression and domination, anti-Blackness, and the pernicious ideology and structure known as neoliberal capitalism driving extractivist economies, competition, consumerism, privatisation and human disconnectedness.

In recent work surveying researchers and practitioners about their experiences and meanings of the decolonial turn (colonialism as a fundamental problem in modern society), people highlighted several orientations that were reflective of their positioning and social location in a particular country (Fernandez, Sonn, Carolissen, & Stevens, accepted). For all those who responded, this longer history and the current spotlight on the crisis calls for what liberation psychologist, Martín-Baró referred to as a new horizon for psychology (Martín-Baró et al., 1994).

For the respondents, this horizon is based in an ethics of relationality, of working with and alongside people to address issues and strengthen resources. The new horizon means having a deep understanding of history and the intersections of race, gender and class that continues to shape intergroup and social relations in the present.

This means understanding the underside of modernity, that is,the side of colonialism, violence, and as our friend and colleague, the late Tod Sloan (2018) commented in his article On waking up to coloniality, that “taking the darkside fully into account requires a reversal of or surrendering of many assumptions of many about reason/knowledge, experience/subjectivity, and society/power”.

For the respondents in our project, the decolonial turn also entails mutual accountability which includes asking questions about to whom are our universities and professions accountable, and it means seriously wrestling with the concept of power, confronting inherited and unearned entitlements including those afforded by white supremacy and socialised ignorance produced within the dynamics of dispossession and advantage.

Power, dialogue and mutual accountability

So what does this moment mean for anti-racist psychological research and practice in the Australian context and can we sustain this beyond the current moment that has produced so many ruptures to everyday work and social lives?

Our aim is not to offer recipes, but based on our struggles to create spaces within and outside the university to develop forms of praxis, that is, the interlinked cycle of critical theory-action-theory, that disrupt forms of symbolic and structural violence, and fosters human development.

This orientation invites openness and the embrace of uncertainty. Brazilian educator Paolo Freire (1972) emphasised the importance of dialogue to praxis. He wrote: “Dialogue cannot exist, however, in the absence of profound love for the world and for women and men. The naming of the world, which is an act of creation and recreation, is not possible if it is not infused with love. Love is at the same time the foundation of dialogue and dialogue itself. It is thus necessarily the task of responsible subjects and cannot exist in a relation of domination” (Freire, 1998, p. 77).

Along similar lines, Owens (2020) reflected on love and rage and noted that these emotions go hand-in-hand in the path to personal and social liberation. For him liberation – the idea of freedom – is not just an abstract ideal, but it means that one is able to live without systems of violence and to not enact systems of violence on others.

We want to encourage a deeper radical engagement with the challenges confronting us in the current moment, our history, and the present. We have resources available to do this (see InPsych, 2013 volume 35 issue 3), as well the wealth of material available online, but we can go further to centre the writing of First Nations people (see Australian Indigenous Psychology Education Project; www.indigenouspsyched.org.au), and other groups whose experiences, wisdom and knowledge remain at the margins of our discipline and profession.

More specifically, the current global context has presented us with significant challenges and opened up opportunities to think beyond the boundaries of our discipline to enact new horizons. Academic and activist Clare Land (2015) has provided some very useful critical tools for non-Aboriginal people who want to get involved in and conduct their everyday lives committed to anti-racism and decolonising action.

Recognising the complexity of the matter, the suggestions are based on the understanding that Indigenous people want sovereignty to be acknowledged, truth-telling about our history, safeguarding of country and heritage, recognition and respect for Aboriginal culture, representation at all levels of civil society and payment of reparations.

Psychology and change

The Black Lives Matter movement has reignited the need to address these issues and, for many, these questions have stirred a desire for action. Land (2015) has provided some guidance about actions that people can take in response to these various categories ranging from participation in learning circles to structural change to ensure Indigenous representation and active engagement in our institutions. Others (e.g., Dudgeon & Walker, 2015; de Sousa Santos, 2014, 2020) have suggested ways in which to decolonise universities, disciplines and professions more broadly.

The suggestions include that we recognise the plurality of knowledge systems and the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) roots of psychology; enact deep listening to learn from those outside our lifeworlds; learn and ask critical questions about our inherited knowledge systems (i.e. theories, methods, practices) and who they benefit; ask as others have – what does the world look like from where we stand outside Eurocentricism (see Ratele, 2019); to ask how colonial and patriarchal ‘mentality’ saturates ways of doing and being and find ways to disrupt these norms.

The work of Paola Balla (2020) Wemba-Wemba and Gundijmara woman provides powerful examples of how arts and arts practice can be utilised in community and counselling contexts as unsettling aesthetics. Through her visual arts practice Paola has documented the legacy of coloniality as well as the ways Aboriginal people have resisted, survived and thrived On Country. Art is a powerful medium that invokes various senses and can challenge the audience in deep and unsettling ways, opening spaces to bear witness. Art is a vehicle for healing, for politics, for resistance, and for personal and collective change.

As Fine (2018) noted, we need just methods in these contentious times, and we need to unsettle our psychology as a project of solidarity. Widening our scope of practice through justice-oriented methods rooted in a practice of unsettling is what we need because the status quo won’t suffice. We can get closer to this through critically interrogating our cultural roots and intersections with structures, nurturing rather than diminishing the ways of being of cultural groups, and embracing discomfort as an opportunity for growth and awareness raising in the process. We may also get closer by asking what are the costs to communities and people if we remain unchanged, if we continue to be complicit in epistemologies of ignorance?

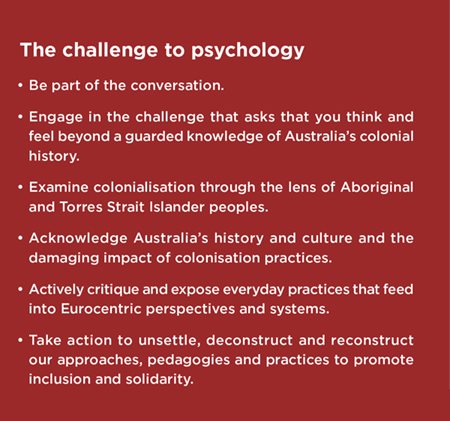

These are very useful questions and potential guidelines inviting us individually and collectively to begin the processes needed to unsettle, to deconstruct and reconstruct our approaches, pedagogies, and practices to serve all people to foster solidarities. We understand that the work of decolonising and enacting anti-racism in the everyday is not easy and will entail unique challenges and demands for different people, but there’s no time to stand on the sidelines. The challenge for us as critically minded community-oriented people is to make the commitment and together navigate the challenging, emotionally tough, discomforting, unsettling work of self, disciplinary, and social transformation.

The first author can be contacted at [email protected]