Throughout the various locations and dimensions of our workplaces, psychologists have the daily – at times hourly – privilege and responsibility of sharing in the lives of our clients, whether that is through assessment, therapy, research or test administration. Psychologists are frequently called upon to make risk assessments across a broad range of issues, from suicide risk to domestic violence. We undertake these risk assessments cognisant of the seriousness and weight of responsibility that comes with such tasks. At the same time, we have procedures and competencies that allow us to conduct those assessments with a level of confidence such that we are neither burdened by nor flippant about the process. We recognise warning signs and we can respond appropriately.

As psychologists, it is time to expand our skills into a new area of risk – understanding and assessing clients who may be at risk of radicalisation. There may be clients who come to us who may be particularly vulnerable in key areas of their lives, and simply by lack of awareness, we might fail to pick up on these early warning signs and therefore miss opportunities for intervention.

Extremism in context

Violent extremism presents a serious threat to our national and international peace and security, negatively affecting many members of our global family. Violent extremism is the belief that fear, terror or violence are justified tools to use in bringing about social, political, religious or ideological change (Living Safe Together). Close to home, the Christchurch attacks at the Al Noor Mosque and Linwood Islamic Centre in March this year resulted in 51 people killed and 50 injured. Australians are affected by these events and others like them because they can shatter the community’s sense of safety and cohesion. We are affected because, as a community, we share in the grief, anger, fear, and importantly, in the need to make sense of these horrific events. Beyond that, we share the responsibility to build societies that are safe, peaceful and harmonious for all. Without a concerted effort to fulfil this responsibility, there is potential for further alienation and marginalisation that can result in some people becoming psychologically vulnerable, isolated and at risk of radicalisation.

The pathways

The task of countering violent extremism (CVE) is complex and has captured global, national and statewide attention. There are controversies surrounding the approaches, measurement and success of CVE efforts, but the ultimate goal is universally shared: to prevent the use of violence as a means to achieve a political, religious or ideological end. Psychologists face the challenges associated with helping to build a cohesive society where those who are vulnerable to radicalisation receive support, treatment and interventions appropriate to their risk and needs, while balancing the safety of the community and the civil liberties of the client. We do this in keeping with our ethical standards.

Achieving this task requires an understanding of the radicalisation process. The pathway to radicalisation is different for every individual, comprised of highly complex and nuanced issues and motivations (Jensen, Atwell, Seate & James, 2018). At a broad level, there are three key domains of which to be aware:

- Social relations – withdrawal from friends and/or family and engagement with a group.

- Ideology – holding aggressive, hostile views that are ideologically founded.

- Criminal activity – engagement in low-level crime justified by political, religious or ideological views.

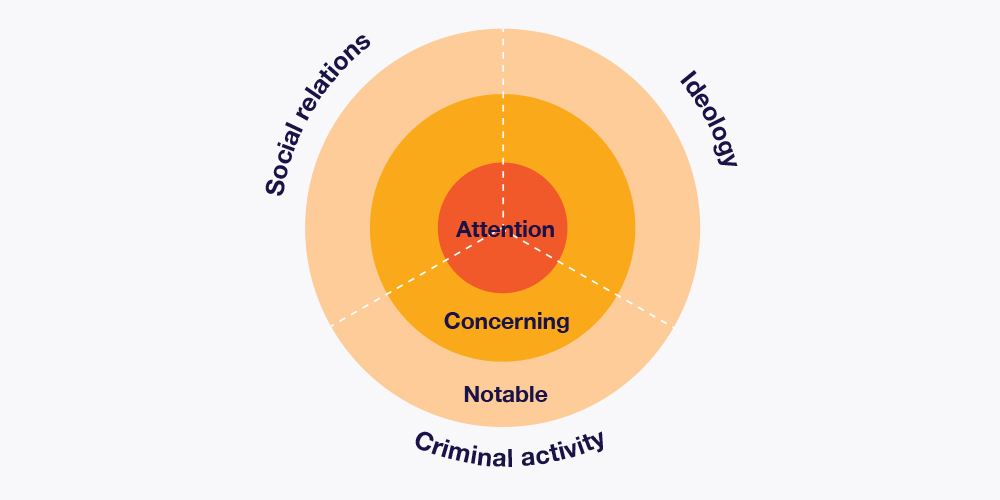

Client behaviours in each of these categories will inform the level of concern, treatment target and referral pathways. In identifying, understanding, assessing and responding to these domains, the Behavioural Indicators Model (Attorney-General’s Department, 2015) can provide guidance. The model, adapted from Barelle’s Pro-Integration Model (2015), identifies three levels of concern in each domain: notable, concerning and attention. An understanding of the types of behaviours a client might demonstrate at each of these levels is critical for adequate risk assessment and intervention.

Assess risk and take action

Interventions will vary depending on the domain (i.e., social relations, ideology, and/or criminal activity), level of concern and risk assessment outcomes. Adequate understanding and recognition of warning signs will facilitate psychologists in determining appropriate interventions and referrals. Equally, psychologists must be able to identify when it is necessary to take immediate action to prevent harm to others or self.

In undertaking a risk assessment and determining a course of action for clients who are at risk of radicalisation, it is critical to apply appropriate frameworks and theory, which will in turn, inform intervention type and referral needs. Competing ethical obligations can complicate this already difficult decision-making process, making a defensible decision-making framework imperative. Such a framework not only assists in navigating the complexities of such situations, but will also assist you to practise with confidence, knowing that if your decision in regard to the client were to be scrutinised, you would have sufficient evidence of its defensibility.

Online training

The Australian Psychological Society has received funding from the Queensland Police Service to develop an online training package to train psychologists in working with individuals at risk of violent extremism. This training package will provide an introduction to key concepts, issues and principles related to violent extremism and radicalisation.

In a stepped-learning process, the training will examine drivers of violent extremism and explore relevant individual factors and contextual issues that affect a person’s vulnerability and motivation. On successful completion of the training, psychologists will be able to:

- define violent extremism and radicalisation

- identify the issues, motivations and individual factors that are relevant to the radicalisation process

- recognise signs of radicalisation and identify level of concern using the Behavioural Indicators Model

- detail key theoretical frameworks that explain the radicalisation and de-radicalisation process

- delineate the role of the psychologist within the global, national and state efforts to counter violent extremism

- navigate the complex task of balancing ethical, legal and professional duties that may conflict with one another

- apply risk assessment approaches to clients who may be vulnerable

to risk of radicalisation to

determine appropriate treatment and referral responses

- implement decision-making frameworks that, regardless of client outcomes, will enable psychologists to provide sufficient evidence of defensibility, should the decisions made in relation to that client

be scrutinised.

The training will take approximately 10 hours to complete and will be freely available online to all psychologists. See bit.ly/2kqPoi7 for more information.

Enquiries can be sent to [email protected]