We all experience some level of attachment to our possessions. This can be for many reasons, whether it is about the enjoyment they provide, the social status they signify, the practicality of future use, or the memories that they inspire. It is normal for our possessions to reflect and inform our identity. However, for some individuals, attachment to material possessions can become problematic and impair their quality of life. This is when treatment for hoarding disorder may be helpful.

Hoarding disorder is defined by difficulty discarding material possessions, accompanied by frequent accumulation of possessions and cluttered, disorganised living spaces. As hoarding disorder is a new diagnosis, first presented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), working with clients with hoarding difficulties is an under-represented topic in many psychology training programs. It is important for psychologists to develop a working knowledge of hoarding disorder, because hoarding severely impacts individuals and the community, and may become a more frequent diagnosis due to broader sociocultural factors. This article aims to inform psychologists about our current understanding of hoarding disorder, and to introduce therapeutic techniques shown to be effective in treating hoarding.

Diagnosing hoarding disorder

The DSM-5 provides a framework for diagnosis. Specifications can be made regarding whether excessive acquisition of possessions is especially problematic, and also regarding the degree of insight that the client presents. Lack of insight is common in hoarding disorder, and instances exist where clients have refused to acknowledge a problem despite being physically unable to enter their home due to the build-up of possessions.

Another useful framework for thinking about hoarding symptoms is reflected in the Saving Inventory–Revised (Frost, Steketee, & Grisham, 2004), a questionnaire measure of hoarding. Symptoms measured by the inventory are divided into three dimensions: (i) accumulation of possessions; (ii) clutter and disorganisation; and (iii) difficulty discarding. These groupings are useful as they allow individual differences in client experience to be easily identified. For example, some clients may rate highly on clutter and disorganisation, whereas other clients might still have a problematic quantity of possessions, but attempt to be quite neat in the way that these possessions are stored. While the DSM-5 criteria prioritise difficulty discarding as a reliable distinguishing feature of hoarding disorder, the Saving Inventory–Revised presents a useful framework for informing individual client work.

The point prevalence of hoarding disorder is estimated to fall between two and six per cent in Western countries. Characteristic lack of insight and the recent formalisation of the hoarding disorder diagnosis suggest that prevalence is more likely to be underestimated than overestimated. There is some evidence that hoarding is more common in males, although females are more likely to be in treatment. Most individuals in clinical samples are aged 50 or older, however it is common for clients to report that hoarding-consistent cognitions, emotions and attitudes (e.g., aversion to waste) have characterised them since childhood. Cross-cultural prevalence figures appear to be similar to those of Western samples, although this is an area that requires further study.

Explanatory framework

The psychological causes of hoarding are broadly understood, with the leading cognitive-behavioural model suggesting that four major factors influence hoarding development: (i) dysregulated emotional attachment; (ii) information-processing deficits; (iii) unhelpful beliefs about possessions; and (iv) behavioural avoidance (Frost & Hartl, 1996).

Strong emotional attachment to possessions is the core characteristic of hoarding. Individuals with hoarding disorder tend towards poorer emotion regulation capacity, experience negative emotions acutely and perceive negative emotions as more threatening. Many clients report a background of emotional deprivation and experiences of sudden traumatic loss. An understandable explanation for hoarding disorder is that individuals whose early childhood attachment bonds have been disrupted in some manner refocus these attachment bonds on their material possessions. This acts as an emotional containment mechanism promoting feelings of safety, security, identity, and control, with the stability of material possessions an attractive counterpoint to the transience and unpredictability that can be associated with interpersonal relationships.

Information-processing deficits are also a key theme in individuals with hoarding disorder. These deficits include difficulties with concentration, categorisation, inhibitory control, flexibility of thought, planning, decision-making, and visuospatial memory. This cognitive profile of hoarding disorder is markedly similar to that of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and as many as 28 per cent of individuals with hoarding disorder may warrant a comorbid diagnosis of inattentive ADHD. Presently, it is believed that information-processing deficits constitute a shared vulnerability factor for ADHD and hoarding disorder.

A number of unhelpful, unrealistic and all too often rigorously defended beliefs are commonly linked to hoarding behaviour. Themes include identity (“Losing this would be like losing a part of myself”), overvalued responsibility (“It will be my fault if this ends up in landfill”), fear of information loss (“If I throw out the newspaper, how will I remember what happened today?”), and perceived future need (“If I get the same car in the future, then these parts will come in handy”).

A personality trait connecting many of these themes is perfectionism, with perfectionism in hoarding being associated with the fear of making mistakes, a need to have everything exactly right, and paralysing inaction when faced with uncertainty and the possibility of later regret.

Finally, negative reinforcement of avoidance is a core process driving and maintaining hoarding behaviour. Avoidant behaviour is pervasive across hoarding, present in the form of poor motivation, lack of insight, denial, slowness, tardiness and procrastination. This behaviour is reinforced, as it generates a barrier against the anxiety, grief, regret, and uncertainty that individuals would otherwise need to confront and manage were their hoarded possessions lost. Unfortunately, avoidance also limits the individual and perpetuates other problematic consequences of hoarding, and the breaking down of avoidance is a key goal of psychotherapy for hoarding.

Distinguishing hoarding from OCD

The DSM-5 places hoarding disorder in the ‘Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders’ section. The disorders in this chapter are characterised by problematic patterns of behaviour that are repetitive, preoccupied and driven in nature. In fact, prior to its appearance in DSM-5, hoarding was initially believed to be a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). This is now an outdated way of classifying hoarding, with modern understanding suggesting that hoarding disorder is more usefully thought of as separate and distinct from OCD.

What evidence differentiates hoarding from OCD? Hoarding symptoms are more common and do not always co-occur alongside OCD symptoms. Factor analysis has shown hoarding to be statistically distinct from traditional OCD symptoms (e.g., checking, counting, washing), and when hoarding behaviour warrants an OCD diagnosis, it is more likely to be highly stereotyped and bizarre in nature (e.g., feeling compelled to store bags of household waste within the home). Biologically, there is relatively low genetic overlap between hoarding disorder and OCD, and neuroimaging implicates differing neural pathways.

A key challenge in treating hoarding behaviour is that hoarding is ego-syntonic, and seen as an authentic (if not wholly desirable) characteristic of the client’s self. In contrast, OCD obsessions are predominantly ego-dystonic, and viewed as a distressing experience inconsistent with the self. Finally, traumatic past experiences are more common in hoarding disorder than in OCD, and best-practice OCD treatments have not been particularly effective in treating hoarding, adding to the weight of evidence suggesting that we should be thinking about hoarding as a distinct phenomenon.

Is it a hoard or a collection?

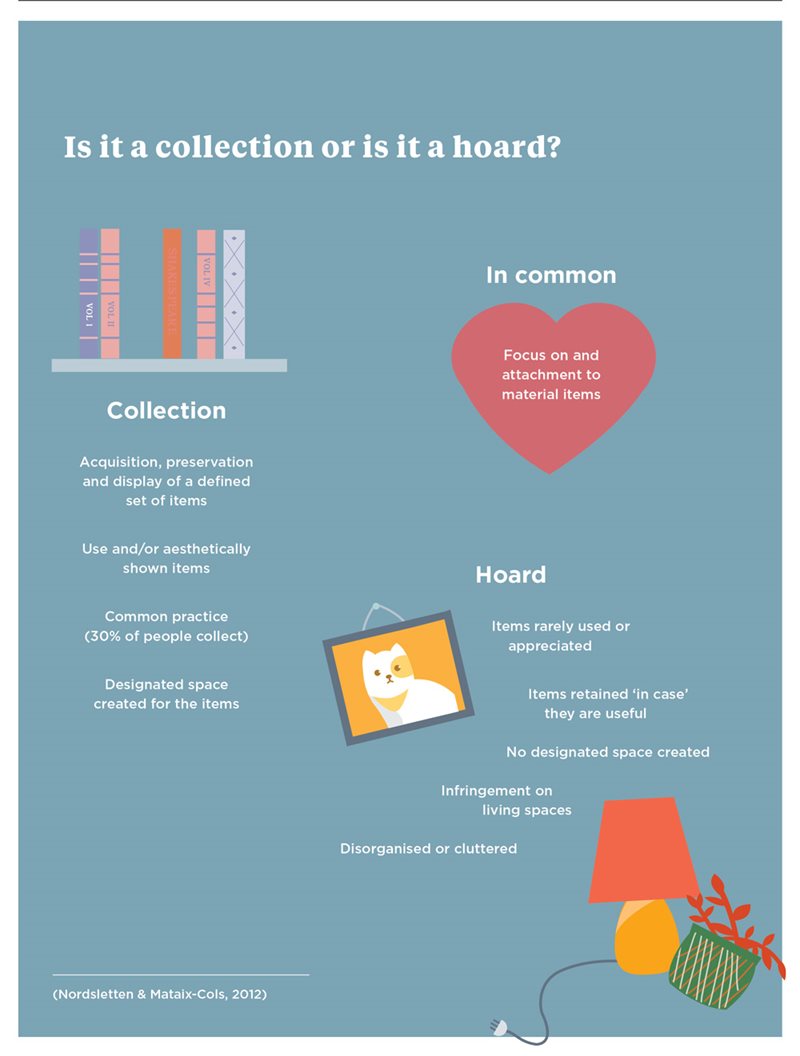

Collecting is a non-pathological hobby centred on the acquisition, preservation and display of a defined set of items. Hoarding and collecting share common features in terms of their focus on and attachment to material possessions. At present, few studies have been conducted attempting to differentiate hoarding and collecting. Nonetheless, three useful distinctions have been identified (Nordsletten & Mataix-Cols, 2012).

1. Collecting is a relatively common hobby, with approximately 30 per cent of people endorsing that they engage in collecting to some extent.

2. Collectors are more likely to use their collected items (with “use” in this sense also encompassing aesthetic display). In contrast, individuals with hoarding difficulties commonly assert that a possession is important as it has a use or will be used in the future, but paradoxically these possessions are rarely used or appreciated.

3. Collectors are more likely to organise a specific space within the home to contain their collection, rather than their collection spilling across rooms, over floor space, or compromising intended use of living areas.

Pilot data suggests little association between collecting behaviour and vulnerability to hoarding within a general community sample. As clients with hoarding difficulties may describe themselves as collectors to rationalise avoiding discarding, psychologists are advised to search collecting websites and forums, as well as sold listings on online auction sites, to inform their thinking around whether normative collecting behaviour is occurring.

Contents and consequences

Hoarding is a multi-level problem, and psychotherapy must address not just individual thoughts, feelings, and behaviour but also the physical manifestation of the hoard. Although virtually anything can be hoarded, common themes occur across clients. While terms such as ‘junk’ might seem pejorative, the reality is that possessions in a hoard usually fit this description, tending to be of low financial value, in poor condition or outright disrepair, relatively easy to reacquire if needed, and unlikely to be perceived as meaningful by others.

Clothing, kitchenware, haberdashery, ornaments, toys, hardware and automotive parts are all common items to find in a hoard. Books, magazines, newspapers, catalogues, brochures and documentation such as old bills are usually present, speaking to a fear of information loss. Food can be hoarded, likely accompanied by squalor. Possessions inherited from deceased estates can be especially problematic, due to both their quantity and their association with grief and loss.

Animal hoarding is a particularly problematic subtype of hoarding. Rabbits, dogs, birds, and horses have all been observed in animal hoarding cases, but the most commonly hoarded animals are cats. Animal food and waste elevate squalor concerns, and humans in the home are at risk of parasite infestation and zoonotic transfer of disease. Hoarded animals face deteriorating living conditions and their own health concerns, and accordingly, animal hoarding is often brought to the attention of health professionals by veterinarians.

Animal hoarding is especially difficult to treat, because clients are motivated by wanting to care for animals, but lack insight into their lack of capacity to provide this care. The absence of evidence-based interventions specialised for animal hoarding is a major obstacle to treatment, and sadly hoarded animals are often euthanised, as their number and health issues complicate rehoming them.

The consequences of hoarding are severe, and affect the individual experiencing hoarding difficulties, family members and pets who may be living in the home, and the local community. Clutter elicits stigma and reinforces social isolation, as individuals tend to feel ashamed about inviting others into the home. Hoarded possessions constitute a tripping/falling hazard, a dire risk when one considers that many experiencing hoarding difficulties are older adults who live alone. Homes are often afflicted by squalor, increasing risk of illness and infection.

Hoarded possessions also pose a fire hazard, with as many as four out of five fatal fires occurring in homes with excessive clutter. Finally, the financial burden of remedying home disrepair, disposing of hoarded possessions, navigating legal processes, and treating hoarding disorder is considerable. These outcomes underscore the importance of continuing to improve treatment for hoarding disorder.

Psychological therapies

The most effective evidence-based treatment for hoarding disorder is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Buried in Treasures (Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2014) is an accessible and evidence-supported guide to managing hoarding symptoms that is written as a self-help text for clients and their families. A formal guide for clinicians is the Treatment for Hoarding Disorder: Therapist Guide (Steketee & Frost, 2013), which is consistent with the Buried in Treasures framework. The introduction to assessment and treatment of hoarding found below is based on these texts, and psychologists working with hoarding disorder are strongly advised to access them.

Assessment

Assessment consists of a structured client interview, the completion of psychometric questionnaires, and ideally, a home visit (provided that the psychologist feels safe and has sufficient rapport with the client). A number of tools are available to assist with the assessment process. The Saving Inventory–Revised is one of several widely used symptom assessments, and the Activities of Daily Living Scale assesses functional impact. The Clutter Image Rating Scale allows hoarding severity to be rated visually by room. The picture of the problem that the assessment process provides should allow the psychologist and client to start planning the decluttering process.

Treatment

CBT for hoarding follows a process of identifying goals, teaching organisation and problem-solving skills, and conducting behavioural experiments to strengthen emotion regulation and challenge avoidance. Some clients might be self-motivated to engage in this process, but for others, a harm-minimisation approach (making their home safer) or wellbeing-based approach (owning fewer, more important possessions to maximise enjoyment and appreciation) can be an effective way of inviting collaboration. A useful strategy when treating hoarding is to focus on acquisition, clutter and discarding as different elements of treatment.

The basic principle of working with acquisition is simple mathematics: if the amount of possessions entering the home exceeds the amount of possessions leaving the home, then hoarding will not improve. When encouraged to record incoming possessions, clients will often be surprised by how much they have underestimated their acquiring behaviour. Impulse-control strategies are helpful in managing acquisition, and helpful pre-acquisition techniques include waiting a certain amount of time (e.g., 30 minutes, overnight), asking oneself a set of reflective questions (e.g., “Will I still value this possession a year from now?”), and consulting with a supportive friend. Behaviour management and exposure work can focus on situations that facilitate acquisition, such as visiting an op-shop or spending time on online shopping sites when bored.

The sheer physical task of decluttering a hoarding home would be overwhelming for anyone, even without the strong emotional attachments that complicate hoarding disorder. Realistic goals are important here, as while it seems an impossible task to clean an entire home, breaking this down by rooms or even shelves starts to make decluttering feel achievable. Skills-training is essential, as many individuals with hoarding difficulties have lost touch with the organisational skills needed to maintain a tidy home. Clients benefit from support with categorisation and sorting principles, and with making decisions about how possessions will be disposed of.

Indecisiveness is particularly problematic when decluttering, and an important rule is to only handle possessions once when sorting them. This is because avoidance can drive clients to place items back in the hoard rather than making decisions about them, a process known as churning. When client motivation wanes, remind them of the values and aspirations that brought them to psychotherapy in the first place.

Talking about discarding is not enough – a hoarding problem will never get better unless the client is able to let go of some of their possessions. However, clients must be aware that they will not be forced to discard anything against their will, as this is tremendously damaging to rapport. In a discarding exposure, the client is asked to rate the distress associated with discarding a specific item, and to estimate how long that distress would impact them. The client then tests their predictions by discarding the item. The aim of this exercise is for clients to learn that they will eventually habituate to the negative emotions associated with discarding.

It is noteworthy that rather than anxiety, the primary emotion associated with discarding is grief. Accordingly, the psychologist needs to be ready to support the client with any regret over their discarding decisions, and to keep them in touch with the positive future that they are moving towards by reducing their hoarding.

Treating hoarding is a multi-level problem that requires a multi-level solution. CBT is the most effective treatment at present, but there are still many clients who do not respond (Tolin, Frost, Steketee, & Muroff, 2015), and hence clinicians and researchers need to continue to explore helpful strategies. For some clients, antidepressant medication in combination with psychotherapy can heighten engagement and promote greater treatment effect. Family and friends should be educated to provide appropriate support, and social workers or professional organisers trained to work with hoarding disorder can be useful in-home adjuncts to treatment.

Where possible, cases of hoarding disorder should be registered with fire brigades to help them to monitor risk and plan suitable fire assistance. Liaising with landlords, council workers, and human services is also essential, and local governments are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of managing hoarding within the community (see bit.ly/2ksIJnB for a leading Victorian example).

Predicting the future

What lies ahead for hoarding disorder in Australia? Population growth and increased housing density are resulting in smaller dwellings, and a worst-case scenario is that this will increase the prevalence of hoarding disorder. This could be countered by changes in social norms regarding the amount of possessions that an individual owns. Movements such as minimalism and environmentalism challenge the tendency for individuals to over-consume, and the shifting of entertainment media such as books, movies and video games from the bookshelf into online spaces might also have a positive effect. What is certain is that psychologists will have a prominent role in helping to manage hoarding in the future, working with both individual clients and the wider community in order to deliver more effective treatment paradigms.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]