Interest in how best to teach children who experience difficulties learning to read and write goes back to the 19th century. In 1877, German physician Adolph Kussmaul made the first diagnosis of what he called ‘word blindness’ and in 1887 a German ophthalmologist coined the term ‘dyslexia’ to describe this so-called word blindness. The first academic paper on the topic of dyslexia was published in 1896 in the British Medical Journal, by William Pringle Morgan.

Definitions of a disorder in learning vary widely but the most commonly accepted definition is that adopted by the American Psychiatric Association: “the learning difficulties are not better accounted for by intellectual disabilities, uncorrected visual or auditory acuity, other mental or neurological disorders, psychosocial adversity, lack of proficiency in the language of academic instruction, or inadequate educational instruction” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The timing of the emergence of interest in children with reading difficulties is not surprising, as mass schooling did not commence in most countries until the 19th century (earlier in Germany). The challenge of how to teach basic knowledge and skills to large numbers of children and how to help those who struggled was the impetus for the development of whole new branches of psychology, including the measurement of intelligence and the study of learning difficulties.

The establishment of dyslexia as a category of learning difficulty resulted in research programs to understand the basis of the disorder and the founding internationally of a wide range of institutes and societies to study it, promote its recognition by education authorities and provide support to sufferers and their families. It took until 1987 for dyslexia to be recognised as a learning disability in Britain and until 1992 for it to be outlined in Australia under The Disability Discrimination Act and by the Human Rights Commission. It is still the case that NSW is the only state in which dyslexia is recognised as a disability; in other states it is described as a ‘learning difficulty’.

Despite the slow pace at which dyslexia achieved recognition as a difficulty/disability the term long ago entered common-sense understanding of children’s learning to read. Some early attempts to understand why some children struggle have become ‘common knowledge’ and psychologists may find family members reporting concern about the disorder after noticing a young child’s producing reversed letters; a normal development and not indicative of insipient reading disability.

Prevalence around the world

The estimated incidence of reading difficulty/disability varies considerably, both within English speaking countries and internationally. The signs of the disorder also vary by culture. Estimates for the rate of occurrence in Australia vary from 10 to 16 per cent, while in other English speaking countries the estimate is similarly varied and often high: 5 to 20 per cent in the United States and Canada.

In non-English speaking countries the rate varies in instructive ways. For example Japan has two writing systems, Kana and Kanji. Japanese readers assessed while using the syllabic Kana writing system were estimated to have a prevalence rate of 2 to 3 per cent but when these readers were assessed using the logographic system, Kanji, the prevalence was 5 to 6 per cent. The prevalence of dyslexia in Chinese speakers has been estimated to be around 3.9 per cent, which is similar to the prevalence for Italian (3.1 to 3.2 per cent), and German (1.9 to 2.6 per cent) children who test normally on other measures of competence. In addition children with a reading disability in English speaking countries display difficulties with decoding words while poor readers in other language communities usually display adequate decoding skills but very slow reading.

These figures highlight two important points: that there is some universal, probably neurological, basis for difficulty learning to read but language itself contributes to these difficulties. In terms of discovering the physical cause for dyslexia progress has been slow. Various causes have been proposed, with everything from visual problems to walking too soon. In terms of the latter notion, the lack of experience crawling supposedly prevents the brain from ‘integrating properly’ thus leading to difficulties with later skills development, including reading. These various unsupported theories have provided fertile grounds for those who wish to market ‘solutions’ to schools and worried parents. These include everything from glasses with coloured lenses to programs of movement and exercise and the success marketing these products has assured that the otherwise discredited ideas remain in circulation.

Even more sophisticated attempts to understand the physical, probably brain-based cause of reading difficulties, have not to date yielded any uncontroversial, replicable results, as noted by Julian Elliott and Elena Grigorenko, who conducted and published a thorough review of the dyslexia literature, covering cognitive, neural, genetic and educational/therapeutic aspects. Some of the difficulty may be explained by failure to find a way to distinguish the ‘true’ dyslectic from the ‘merely poor’ reader, which would make finding distinct physical signatures of dyslexia very tricky. This difficulty leads some theorists, including Elliott and Grigorenko (2014), to cast doubt on the existence of dyslexia as a separate distinct disorder. Nonetheless there are some promising preliminary results of neurological studies that may provide an explanation of why some find reading such a difficult skill to master. As yet these remain useful for explaining the disorder but not as a guide for treatment.

Popular as a contributing factor to dyslexia is phonological awareness, defined as a person’s ability to hear the individual sounds of a language. Much attention is given to the necessity of developing children’s phonological awareness before attempting to teach them to read. The picture is complicated by findings that demonstrate that phonological awareness grows as part of learning to read. However, despite its popularity this factor remains controversial. As Ramus (2014) notes:

“…it is obvious that phonological deficits play a causal role in certain types of reading disability, but not in all of them. A similar point could be made for other subtypes of dyslexia with distinct cognitive deficits (visual, or visuo-attentional). The problem, however, is that whereas it is clear that not all dyslexics have a phonological deficit, there are many theories of non-phonological subtypes, and none of them has gained widespread acceptance. This argument therefore awaits further research” (n.p).

The role of orthography

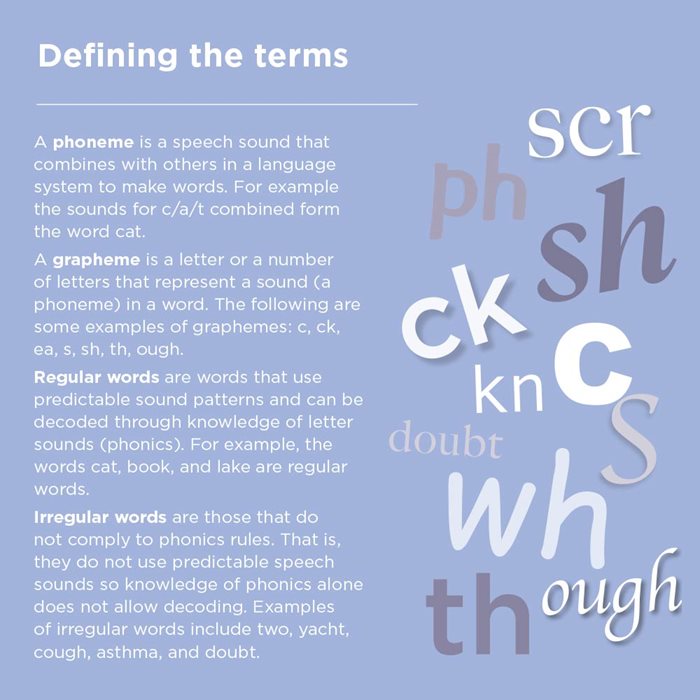

When trying to understand the latter issue – the contribution of language to literacy difficulties, the concept that is favoured is ‘orthographic depth’. Some languages, for example German and Italian, have a very clear and straightforward relationship between phonemes (sounds) and graphemes (their written representations). These languages are said to have a shallow orthography. English – which is not alone in this – has a deep orthography. It has 44 phonemes which must be represented by 26 letters and letter combinations. The complexity of the code is much increased by the language’s origins in German and French (with a good deal of Norse thrown in). The consistency of English spelling also suffered from historical contingencies, including its reinstatement as the official language of England in the 15th century and the efforts of Continental printers during the so-called Bible wars of the 16th century (conflict over the publishing of a Bible in the English vernacular).

As a result, English has the dubious distinction of having the most complex spelling code of any in the world. This is not to say, as many now believe, that the language is completely irregular. The spelling of approximately 50 per cent of words is regular and approximately 36 per cent more are regular except for one sound, usually the vowel. A humorous depiction of English’s ‘impossible’ system is the claim that ‘fish’ might just as well be spelled ‘ghoti’ – the gh from ‘enough’, the o from ‘women’ and the ti from, say, ‘nation’. What this actually demonstrates is some of the regularities in English spelling. Whilst the /o from ‘women’ is an example of an irregular vowel in another wise regular word; ‘gh’ is routinely pronounced /f/ at the end of words: enough, tough, rough and ‘ti’ is a common alternative spelling for the phoneme usually represented by ‘sh’. There are a large number of other spelling principles of which people, teachers included, remain unaware.

It is arguably impossible to teach the complex English spelling code without a good grounding in how it works. A variety of historical contingencies – once again – have conspired to deprive most teachers in English-speaking countries of knowledge of the English spelling code. From the inception of mass education there was fierce debate about how reading should be taught, between those who proposed that an emphasis on phonics and methodically teaching the letter-sound correspondences and those who favoured what has variously been called look-say and whole language methods; that is, methods that teach whole words rather than their constituent parts. The latter won out because of apparent advantages for fluency of the latter type of instruction – in fact students were more fluent because they had been taught to memorise the texts used in tests – and the results of poorly designed early experiments on learning to read.

The reading debate

The dominance of whole word reading techniques has been challenged by a series of longitudinal and experimental studies and the access to increasingly sophisticated technology and imaging techniques that have revealed how the eyes and brain actually work during reading. The latter have shown that expert readers do not decode text at the whole word level but read right through each word, but at such a pace and so efficiently that they are no longer aware that they are doing so. Nonetheless a whole word approach, most recently branded ‘balanced literacy’ dominates reading instruction in English speaking countries, resulting, critics would suggest, in the disturbing statistic that in the US, for example, each test year the percentage of students scoring below proficient in reading varies between the mid-to-high 20s. This exceeds even the higher estimates for the occurrence rate of dyslexia.

Further circumstantial evidence for the harm done by whole word reading approaches can be found in Australia’s declining scores and ranking on the reading sub-scale of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA – an international program conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]), intended to evaluate educational systems by measuring 15-year-old school pupils’ scholastic performance on mathematics, science, and reading. Australian students who participated in the first round of PISA in 2000 had started school around 1990, before ‘balanced literacy’ came to completely dominate reading instruction in Australia. As each new cohort has been tested the percentage of students who were taught to read using whole word methods has increased and Australia’s standing in reading attainment has steadily decreased.

Treating dyslexia

As already noted, at this stage there is little evidence for and consensus about whether there are different types of reading disability and what might be the causal mechanisms for each, making specifying the best invention at this point impossible. What is without doubt, however, is the most effective means of teaching all children to read is a systematic synthetic phonics (SSP) approach (Castles, Rastle & Nation, 2018). SSP differs from an analytic phonics approach in which children are encouraged to ‘sound out’ words. The complexity of the English code makes this an ineffective and error-prone approach.

Synthetic phonics requires the teaching of sound-letter correspondences which are then used to build words. For each phoneme the simplest and most common graphemes that represent it are taught first and these are practised via spelling lists containing words that demonstrate these and decodable readers that contain only words that the child can read via sound-letter correspondences already taught. Certainly what should be avoided are ‘balanced literacy’ approaches in which children are encouraged to use ‘three cueing’, that is, guessing approaches that teach the habits of poor readers, not accomplished ones.

If even with the best early instruction a child is still experiencing difficulties intervention should start early, when difficulties are first noted. A proper assessment, including investigation of hearing and vision, should be followed by careful testing of the child’s knowledge of the spelling code. Once the difficulties are understood remedial work in small groups should be undertaken, including support for the development of phonological awareness, followed by one on one instruction if this fails to improve progress. In all cases the intervention should be structured using the principles of SSP.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]