Collaborative care to enhance quality of life

Before embarking on a discussion of the role of psychologists in dementia, it is important to address the elephant in the room. Dementia is a terminal illness for which there is no cure. This sentence may shock some and seem confronting, however, a diagnosis of dementia is akin to a diagnosis of terminal cancer for which there is no cure and no effective pharmacological agent to halt or reverse disease progression. Accepting dementia as a terminal illness reframes our approach to dementia as a disease and to those people living with dementia. As for all terminal illnesses, quality of life (and death) become of paramount importance to the person living with dementia, and psychologists can and should be a significant resource for enabling the person living with dementia to do so in a way that maximises quality of life.

The importance of early diagnosis of dementia

Dementia is not a disease entity, rather dementia represents a syndrome comprising multiple disease states for which cognitive decline and functional impairment (“dementia”) is the prominent symptom. Dementias range from progressive and irreversible (e.g., Alzheimer’s dementia, vascular dementia, fronto-temporal lobe dementia), to static and reversible forms of dementia. Given the diverse range of types of dementia, with different prognostic outcomes, early accurate diagnosis is essential. Screening tools such as the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) or more specific screening tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) lack sensitivity and specificity for accurate diagnosis, but can be useful when used as a trigger for specialist referral (such as to a neuropsychologist). Ultimately, accurate diagnosis of type of dementia, and differential diagnosis from other conditions that may present with similar symptoms to dementia, requires specialist assessment by a neuropsychologist and/or psychogeriatrician. Depression and delirium are conditions most commonly misdiagnosed as dementia in the elderly. Both conditions are amenable to treatment and rapid improvement in function. Similarly, persons living with dementia are at risk of developing depression and delirium throughout the course of dementia. These secondary conditions typically exacerbate the cognitive and functional deficits of dementia. Failure to identify and treat depression and delirium in persons with dementia can significantly decrease the individual’s underlying functional capacity and level of independence, thereby impairing quality of life. Hence, accurate assessment of secondary conditions is essential both in the initial diagnosis of dementia as well as in maintaining the highest level of functional capacity through the course of dementia.

There is no definitive diagnostic measure of dementia, or for any of the specific types of dementia. Dementia should be considered to be the last diagnostic option, only made after all competing diagnoses have been considered and excluded. The reason for this being that there are no effective treatment options for reversing or halting the decline associated with progressive forms of dementia. The diagnosis of dementia is made on symptoms profile: the pattern of cognitive, behavioural, and functional changes detected; in the context of the individual’s history and having excluded competing diagnostic explanations (e.g., depression, delirium). Despite extensive research into various brain imaging techniques (e.g., structural MRI, PiB-PET amyloid binding, SPECT, functional MRI), biomarkers from CSF and/or blood plasma, and genetic testing (e.g., APOE e4 allele); none of these techniques has clinical sensitivity or specificity for dementia (Laforce et al., 2018). At best, these techniques may offer some additional confirmatory evidence, however, one should remember that a negative imaging/biomarker finding does not preclude a dementia diagnosis nor does a positive finding indicate a dementia diagnosis.

Similarly, there has been a decades long resurgence of attempts to identify a preclinical phase preceding onset of clinical dementia. The most prominent diagnostic term has been Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), which has appeared in the DSM-5 as mild Neurocognitive Disorder (mNCD). While it may be tempting to apply a diagnosis of MCI/mNCD in the clinical setting, extreme caution must be exercised with research indicating that MCI displays a false positive diagnostic rate in excess of 25 per cent across multiple studies (Klekociuk, Saunders, & Summers, 2016).

A diagnosis of dementia

Treatment options

There are no effective treatments to slow, halt or reverse dementia once a clinical diagnosis has been made. The most recent Phase 2 clinical trials of solanezumab, a drug that reduces circulating amyloid, was abandoned following findings that there was no measurable improvement in dementia symptoms or prognosis (Abbott & Dolgin, 2016). While other drugs targeting amyloid burden in the brain continue to be trialled, the amyloidosis hypothesis of Alzheimer’s dementia is coming under increasing pressure for revision. Ultimately, without a clear understanding of the biologic cause of dementia, developing a pharmacological agent that targets an as yet unknown cause is problematic.

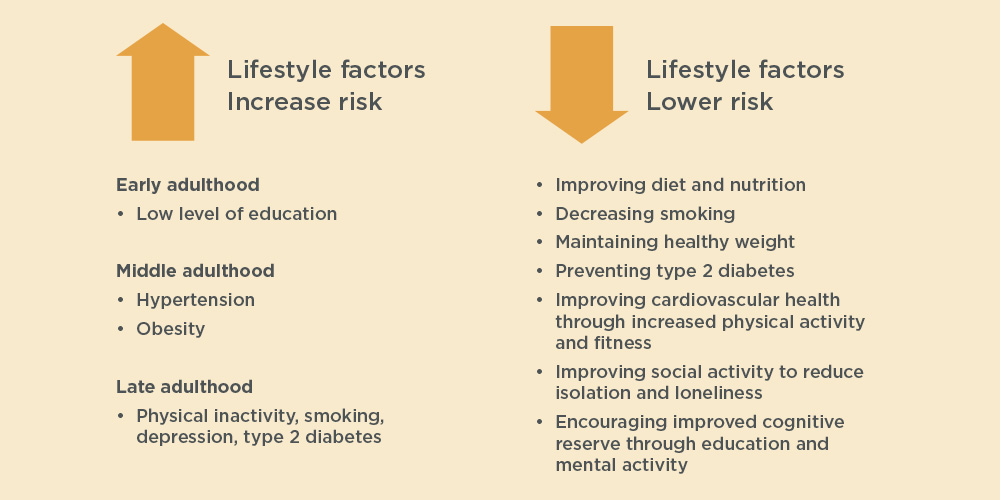

Epidemiological research points to lifestyle factors that are likely to increase an individual’s risk for developing dementia. Low level of education in early adulthood; hypertension and obesity in middle adulthood, and in late adulthood physical inactivity, smoking, depression and type 2 diabetes are collectively thought to account for up to 50 per cent of all cases of dementia in Australia (Hankey, 2018). Consequently, preventative programs targeting modifiable risk factors through improving diet and nutrition, decreasing smoking behaviours, reducing obesity and type 2 diabetes, improving cardiovascular health through increased physical activity and fitness, improving social activity to reduce isolation and loneliness, and encouraging improved cognitive reserve through education and mental activity, may over the longer-term lead to a reduction in the prevalence of dementia. Psychologists have a key role in shaping public policy for the effective implementation of community-wide interventions to modify lifestyle factors across the lifespan.

If we extend the notion of treatment beyond that of the disease mechanism to encompass treating the symptoms of dementia and thereby enhance quality of life for the person living with dementia, there is a marked increase in the range of options available. Treatment planning for dementia is effective where it is: (1) dynamic; (2) collaborative; (3) individualised; and (4) evidence-based. Dementia is not a static disease; disease progression is highly variable and fluctuations in level of capacity over the short-term are not uncommon. Consequently, any intervention needs to be flexible and modifiable to respond to these changes in the person living with dementia. Effective treatments are those that engage with all aspects of the person, at the level of the individual, with their caregivers, with the systems and structures surrounding them, and with the wider environment.

Supporting people with dementia

Dementia impacts across all these levels, with a collaborative response being highly effective in supporting the person living with dementia. It is important to always keep a sense of the person and not fall victim to viewing the person living with dementia as a cluster of symptoms and deficits. For the person living with dementia, the loss of a sense of identity that emerges as increasingly severe memory deficits that impede on recall of personal history, is a significant disabling component. Recognising this loss of identity as a significant source of distress for the person living with dementia is an essential component of any intervention.

Identifying methods to assist the person living with dementia to maintain a sense of self-identity (e.g., photographs, momentos, music, art) is an essential component of individualised therapy. Finally, we should always seek evidence of therapeutic benefit before embarking on any treatment option. As a profession, psychologists must advocate for the use of evidence-based approaches as the field of dementia is replete with ‘wonder treatments’ with no evidence of efficacy and significant financial cost to the person living with dementia and their carers. Good scientific evidence of the efficacy of different approaches such as the recent Lancet Commissions report (Livingston et al., 2017) is a valuable resource for the practising psychologist in this field.

Enhancing quality of life (and death)

Enhancing quality of life and death for a person living with dementia is a process that can be supported by a psychologist. From the initial diagnosis of dementia, psychological support can be critical in assisting the person to understand and accept a terminal diagnosis with an uncertain prognostic course. Identifying and supporting the person and their caregivers through grief following a diagnosis is critical to enhancing quality of life. A key outcome of resolving the individual’s grief is to empower them to regain control of their life. A diagnosis of dementia robs from the person living with dementia a sense of control over their future. Enabling the person to regain a sense of control is central to enhancing quality of life.

Advanced care planning/end-of-life planning is a key component in enabling the person living with dementia to regain a sense of control over their future. This process also empowers family and caregivers to be actively involved and engaged with the individual’s choices about their future care at a time when capacity to make decisions remains intact. Future care planning can uncover the individual’s desire for further care arrangements, plan for a need for legal protection under the relevant state Guardianship and Administration Act (see bit.ly/2STods3), and communicate clearly with family members about the future wishes of the person living with dementia.

Increasingly, high-level supported accommodation (e.g., a secure dementia unit in a residential aged care facility) is an end-of-life, relatively short-term accommodation option for persons with dementia. As such, high-level nursing accommodation is typically used for the final 12 or so months of life. Consequently, the majority of people living with dementia will live in place in the community, the majority of the time in their own residence, and potentially later in different levels of residential aged care. Recognising the need to access in-home care services to meet the changing needs of the person living with dementia is important early on in the process of future care-planning.

Support for carers

Psychological support is also needed for the primary caregiver of the person with dementia as the burden of primary care falls predominantly on them. Ageing in place is only possible where support to the primary caregiver is given to assist them to cope with the demands placed upon them and the impact that full-time caring has on social interaction outside of the home.

An area of concern to caregivers and residential aged care facilities is the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). These symptoms encompass a diverse range of behaviours including wandering, aggressive outbursts, inappropriate behaviours (disinhibition), depression, anxiety, delusions, hallucinations, sleep changes, appetite changes, to name a few. Typically, BPSD appear with advancing dementia and affect the majority of people living with dementia. Careful analysis of potential triggers for BPSD symptoms is required with appropriate management indicated by the trigger and not the symptom, to reduce the incidence of medication misuse in BPSD management. Psychologists offer expertise in the identification of behavioural and psychological disturbances and the appropriate management of such symptoms through behavioural and environmental interventions with pharmacotherapy as indicated.

What does the future hold?

Current prediction models highlight that the incidence of dementia in Australia is about to increase dramatically as the baby boomer generation approaches the age range for dementia onset. Critically, health care systems are underprepared and under-resourced for the exponential increase in dementia on the horizon. Increasingly the burden for dementia care will fall on family as primary caregivers. Psychologists have the skills to provide expert support to the person living with dementia and their care-giver(s) as well as offering expertise to the community and the aged care sector.

Recognising that for the individual living with dementia (and their primary caregiver) social isolation and disconnection from community is a real consequence of the symptoms of dementia. Working with the wider community to advocate for support and engagement for the person living with dementia is a key role for psychologists. Community-level engagement, such as actively promoting and supporting the development of local Dementia Friendly Communities is a proactive way for psychologists to effect system-wide change to the care and support for people living with dementia.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]

Useful resources

For fact sheets for people living with dementia, caregivers and professionals visit Dementia Australia online. Dementia Australia provides counselling support, respite services (in some areas), and other support services for people living with dementia.

Future care-planning resource materials are also available.

Further learning

The Wicking Dementia Research and Education Centre at the University of Tasmania offers two free online (MOOC) courses on dementia which open several times per year: ‘Preventing Dementia’ and ‘Understanding Dementia’. These courses are designed to help improve understanding of dementia for carers, professionals, and any other interested person.

|