The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has renewed discussions about the way we work. We are now questioning the way we work, with much popular opinion suggesting remote work is the way forward. So what of the future of work? And what should we as psychologists have to say about it?

In an effort to respond swiftly to the COVID-19 pandemic, Australian organisations have moved as many employees to working from home arrangements as operationally practical. This has provided an unprecedented opportunity to get a taste of what such an arrangement can be like on a large scale, especially for organisations that did not previously permit working from home or did not have the technological capabilities to do so. With social distancing requirements likely to continue for some time, organisations are looking to establish longer term working-from-home arrangements.

Working from home has typically been considered an employment benefit; a privilege to be enjoyed for the purpose of flexibility and managing work-life balance. However, there is little research available to help understand the impacts of imposed working-from-home requirements, particularly where working from home is an involuntary full-time arrangement. What research is available suggests there are also many drawbacks to working from home, particularly brought about by isolation and lack of boundaries between work and home life.

There is a lot we can do to proactively ensure employers are fully informed when making decisions about the way employees work, enabling arrangements that enhance rather than deplete mental health. But from a reactive perspective, we should also consider potential long-term psychological impacts of working from home, particularly for those that have not had the luxury of choice.

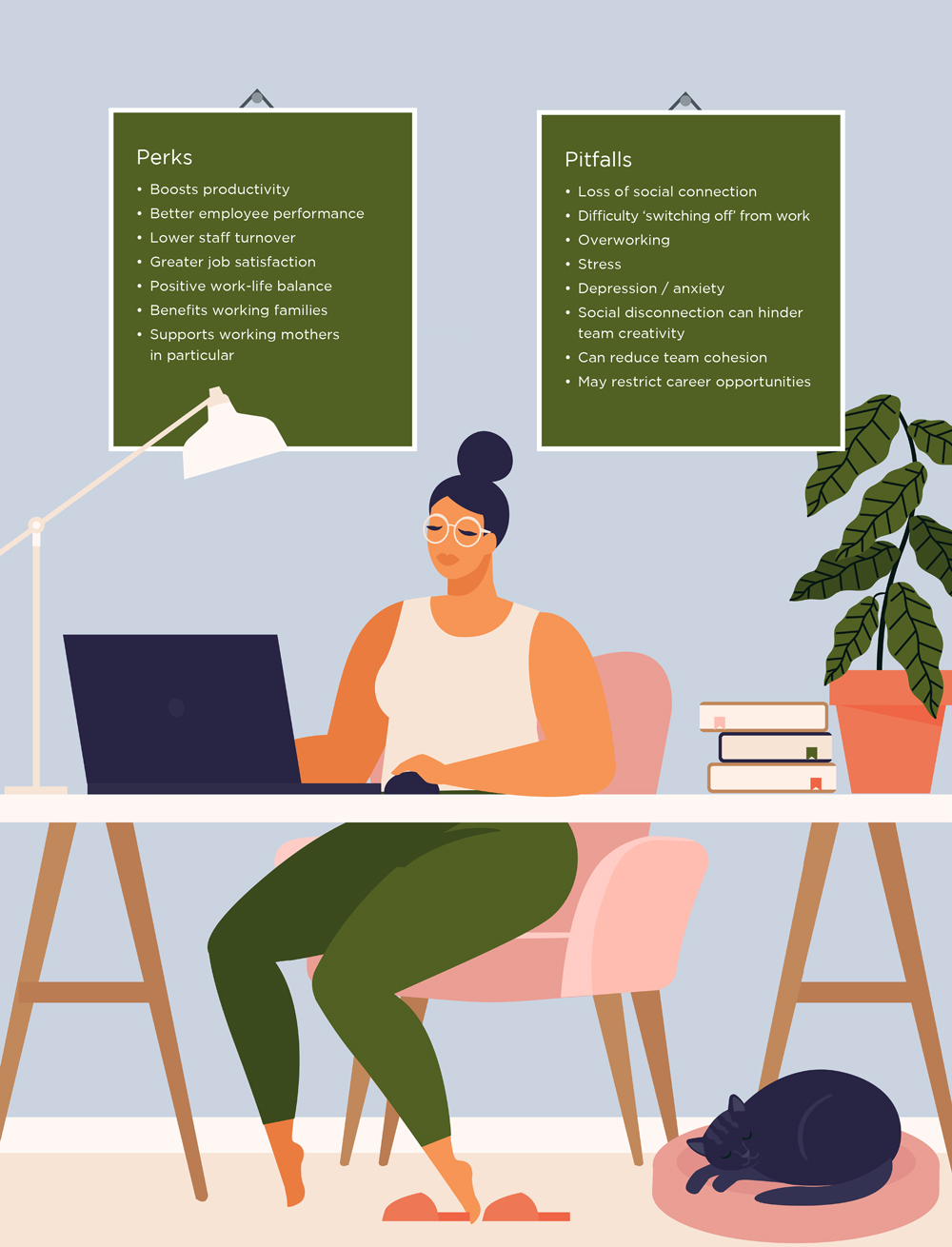

Perks of working from home

For some years there has been a growing trend for organisations to offer flexible work arrangements, particularly in the form of working from home options. Flexibility is often promoted as part of the employee value proposition, enabling workers to attend to family and other personal responsibilities, reducing work-family conflict, and increasing quality time spent with children (Troup & Rose, 2012). It also helps employees escape the noise and distractions of open-plan office environments (Sander, 2019).

Research shows that allowing employees to work from home can result in several mutual benefits, including increased productivity, decreased turnover (Bloom et al., 2015) and greater work satisfaction (Dockery & Bawa, 2014). Furthermore, working from home may improve subjective wellbeing through greater autonomy, control over one’s work schedule, better work-life balance, less time spent commuting and reduced fatigue levels (Song & Gao, 2018).

COVID-19 has certainly provided an opportunity for renewed discussion about the importance of the flexibility and options available to employees to manage the way they work, where and when. Past research has shown that most workers that work from home do so on an informal arrangement, i.e. flexibly as it suits their needs (Troup & Rose, 2012). With greater availability of technology to support remote working, ‘blended working’ has become more common, with employees working from a range of locations (predominantly home) as it suits their needs and circumstances. Research suggests that employees with a strong need for autonomy are generally less concerned with the need for relatedness and work structure, and find that blended working is an effective arrangement because of the control and flexibility it affords (Van Yperen, Rietzschel, & De Jonge, 2014).

Working from home is also associated with increased satisfaction in the distribution of childcare responsibilities, particularly for women, suggesting that women may particularly enjoy flexibility in helping them to respond to family needs and responsibilities (Troup & Rose, 2012). Research suggests women who work at home regularly spend less time on work activities and more time on domestic work and childcare, which may indicate that working from home does facilitate greater work-life balance for mothers, enabling labour-force participation (Powell & Craig, 2015).

Nevertheless the question for many employers has been whether working from home makes business sense. Research by Bloom and colleagues (2015) showed that remote employees can work as effectively as office-based employees when resourced in the same way, with a four per cent increase in efficiency observed for call centre workers (more calls answered per minute), with consistent levels of quality.

Further, Rupietta and Beckmann (2016) found that working from home is associated with increased motivation and work effort. This demonstrates that working from home can work, and employers need not feel concerned about the performance and reliability of employees when out of sight. Bloom and colleagues did also note a vast difference in attrition, with turnover dropping by 50 per cent for home-based workers versus the office-based control group. The increased satisfaction that comes with working from home, greater autonomy and job control, and ability to manage work-life balance appear to be positive drivers of retention, resulting in significant cost savings.

Pitfalls of working from home

Despite a general belief that working from home is beneficial for both performance and wellbeing, on balance the evidence-base does not provide overwhelming support for such arrangements. While Bloom and colleagues (2015) confirmed the performance and productivity benefits of working from home, they also determined that it does not work for everyone. After their experiment, more than half of the workers assigned to the work from home group decided to return to the office, largely due to negative impacts of lost social connection. The employees that continued to work from home were those performing very well.

“COVID-19 has certainly provided an opportunity for renewed discussion about the importance of the flexibility and options available to employees to manage the way they work, where and when”

Working from home has been associated with a range of detrimental outcomes, including decreased social interaction, difficulties psychologically detaching from work, tendency to overwork, stress, depression, and anxiety. Working from home can also hinder team effectiveness and creativity, and result in fewer career opportunities (Sander, 2019). Song and Gao (2018) found that working at home is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing work-related stress and negative affect. A deeper examination of the purported benefits of remote working certainly reveals a gloomier picture.

Working from home may be a ‘necessary evil’ to help cope with increased work demands and long work hours (Dockery & Bawa, 2014), but it may also lead to overworking that otherwise wouldn’t have occurred. Having our work close by at home, enabled by technology, blurs the boundaries between work and home life. According to recent research by Roy Morgan (2020), most Australians who work from home at least some of the time experience greater difficulties switching off than those who don’t work from home.

The European Union conducted research to investigate the impacts of remote work, and found employees who predominantly work from home report being more stressed than those that are office-based (Eurofound and the International Labour Office, 2017). Working from home reduces visibility between employees and managers, and can leave employees feeling pressure to ‘look busy’ and ensure high levels of productivity, which can lead to overworking.

While we all want a sense of work-life balance, we achieve this in different ways. For some, integrating work and home is achievable and works well, for others segmentation is critical. Though working from home is often seen as helpful to managing family demands, bringing the workspace into the home increases the likelihood of work-family and family-work conflict occurring, with the former tending to me more stressful.

A study conducted by Lapierre et al. (2016) demonstrated that involuntarily working from home is associated with an increase in work-family conflict. This effect is more pronounced for workers with low self-efficacy (that is, low belief in one’s ability to successfully juggle both roles). It has been suggested that women may find it most difficult to maintain boundaries between work and family responsibilities, and given that we know that women tend to bear the brunt of household chores and unpaid care, are likely at greater risk of experiencing work-family conflict and the stress that comes along with it (Powell & Craig, 2015).

In contrast, many Australians live alone, and while working remotely, may have very limited opportunities to connect or interact and intellectually engage with others. Research has shown that loneliness is one of the biggest challenges associated with remote working (McCrindle, 2013). A related but distinct issue is isolation, which involves feeling cut off from work and having limited access to the connections, resources and information required to enable job performance. Working from home often sees employees receiving less feedback and recognition, getting less information, experiencing a shift in the way communication occurs, having difficulty tracking co-workers down, not having access to colleagues to bounce ideas around with, and getting less time with managers to discuss work progress (Song & Gao, 2018). Such conditions are likely to ultimately lead to frustration, decreased engagement and satisfaction, and poor wellbeing outcomes.

Finding the balance

Remote working is a double-edged sword. Our current working-from-home arrangements have come about through necessity, and many employees are making the adjustment because they must rather than because they want to. Employers and employees alike have demonstrated resilience and willingness to adapt, but for how long will this flexibility last, what will the future bring, and what will this mean for mental health? Organisational leaders need to take decisive action regarding future plans, but should understand the implications of decisions and balance risk management with meeting both business and employee needs.

While there are clearly wellbeing benefits to be gained from working from home, these are most likely to be derived from situations where employees have full control over when they work from home, can successfully manage the boundaries between work and home life, and have flexibility in work hours. At least for some employees, continued requirements to work from home, and strategies to rotate employees through the workplace due to physical space restrictions, are likely to impact on the mental health of workers. It is our time for psychology to be part of this important conversation.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]