The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is a once-in-a-lifetime event with far-reaching health, social and economic impacts. It is therefore important to understand the effect this pandemic has upon all Australians, and for us as psychologists. Most people predict that life will not be the same after 2020 – but change like this has happened before, for example, after the September 11 attacks in 2001. In light of this, it is also important to consider what social psychology and communication can contribute to our understanding of the current situation and its implications for our future.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Australia has so far involved a small number of deaths (about 100, compared to more than 900 from influenza in 2019) and a relatively small number of infections (just over 7,000 in a population of nearly 25,000,000). More than two-thirds of infections were acquired outside of Australia, and nearly 90 per cent can be traced to known contacts. These statistics are much lower than in other countries, although the number of deaths globally is about the same as the last serious influenza epidemic (swine flu in 2009–2010), and much lower than yearly deaths from HIV/AIDS, malaria or serious flu epidemics in the past (Hong Kong, Asian and Spanish flu). Yet, with the exception of Spanish flu a century ago, the social and economic disruption from this pandemic is much greater.

The Australian context

COVID-19 is a contagious and sometimes serious disease, with a death rate currently estimated at about one per cent. Like influenza, it is worse for people with other health problems, and it has been especially serious in aged-care homes. Due to how contagious it is, significant measures have been required to stop the spread, and fortunately they have been successful in reducing the number of infections. Most people agree that the measures taken have been sensible, given the level of uncertainty about the disease and lack of understanding about how it works. As a result, our health system (unlike some others) has not been overwhelmed and people with COVID-19 have received good care and been quarantined successfully.

Thus, the amount of panic around COVID-19 seems extreme, given the actual consequences of the disease. The economic disruption has been huge, although governments including our own have stepped in to mitigate the worst consequences. At a social level, the disruption is even greater. Many people have been unwilling to see their own families or send their children to school, and most of us have been confined at home. The impact has not all been bad – pollution has decreased, and we have shown endless inventiveness in learning to live and work online. But there are increases in loneliness, family violence and depression – which is not surprising given the context. Many have argued that the current reaction to COVID-19 is worse for health and wellbeing than the disease itself – unarguably, the social cost of this pandemic will be major and long-lasting.

Risk communication and health promotion

What is going on here? And what is the contribution of language and communication, for better or worse? There is more than 50 years of research in social psychology and communication on behavioural contagion. Broadly, it is the tendency of people to react with the emotions they see around them, especially when those emotions are negative, such as fear or anger.

There are many accounts of epidemics of fainting, nausea and other physical symptoms resulting from behavioural contagion. In other words – panic increases panic. We communicate panic interpersonally, through language and nonverbal channels. When looking at the impact of behavioural contagion via the media – how might the use of intense and negative emotional language in the media influence the fear we feel?

Broadcast media, social media and other forms like posters and brochures have long been used to persuade people to adopt health-promoting behaviour. One consistent finding has been that intense language – including fear appeals – is effective at getting people’s attention and promoting preventive behaviour. The quit-smoking campaigns over several decades are a striking example of how successful fear appeals can be at convincing people their behaviour is riskier than they think, and to stop smoking. Likewise, intense and negative language is effective at getting people to reduce alcohol consumption and to adopt sun protection; (see: bit.ly/2XwJnjo for some US research on this subject).

The power of fear

There have been many such studies here in Australia, with similar results. Many years ago, this thinking was applied to the threat of HIV infection and AIDS, at a time when AIDS had no vaccine, no treatment and was 100 per cent fatal. With colleagues, I joined social-psychological research around Australia on safe sex – promoting condom use among gay men and heterosexual men and women (Terry, Gallois, & McCamish, 1993). The first mass-media HIV-prevention ad, the Grim Reaper (1987), and the ads that followed, are spectacular examples of fear appeals. These appeals were certainly effective at putting HIV and AIDS on the agenda for Australians, and they contributed to the social construction of AIDS as a health problem. Indeed, Australia adopted consistent safe sex and drug-injection messages, and facilitated condom use (via dispensing machines in bars and clubs) and safe drug-injection (via needle distribution through pharmacies and specialised clinics), earlier and more effectively than most other countries.

There were, however, some surprises. One was that risk perception, and reaction to risk, is not as straightforward or as rational as one might hope. A kind of risk called ‘dread risk’ (Weinstein, 1980), involves panic about low-probability but very serious events like air crashes or terrorism, combined with unrealistic optimism about the chances of the event happening to us. AIDS shared some features of dread risk, especially for young Australian heterosexual men and women, who were actually at very low risk. They consistently rejected the use of condoms, yet often used extreme communication about the risk of HIV from foreigners, contamination by stepping on needles at the beach, even the need to isolate children with HIV because they might bite others.

This form of extreme communication is called the ‘language of fear’ (e.g., Pittam & Gallois, 2000). One key aspect of it concerned intergroup blaming – AIDS came as a result of other groups’ bad behaviour – which in Australia meant especially foreigners. This kind of intergroup blaming is a common response to fear, and aligns with the belief by many Australians that disease comes from overseas. Unfortunately, some people’s social identity as heterosexuals appeared to be tied to rejection of effective prevention, along with acceptance of unlikely causes of infection.

Some people appear to be more prone to this kind of thinking than others. Hornsey and Fielding (2017) have identified a number of motivations, including personal and social identity – which they call ‘attitude roots’ – that underlie anti-science attitudes about vaccination, climate change and other issues that share aspects of dread risks. These attitude roots may be linked to authoritarian or socially conservative ideologies. They are not amenable to persuasion through reasoned argument, which is very frustrating for scientists. Hornsey and Fielding recommend a non-confrontational persuasion strategy, similar to some psychotherapies, that aligns with the underlying motivation but moves it toward more evidence-based behaviour.

Media and COVID-19

How can we apply all this to COVID-19 and reactions to it? One tempting way would be to look at social media. Certainly, there is good evidence of conspiracy theories, fanciful worries and highly improbable cures and treatments (the kinds of attitude roots Hornsey and Fielding identified) appearing there. People in isolation are also using social media to stay connected. Indeed, social media has proven worthwhile in helping people to find ways of coping with isolation and loneliness. Even so, this may make them more vulnerable to extreme messages. It is important to not only look at social media, but at the mainstream media, which plays a central role in setting the agenda for our attitudes to major events, and is often the fodder driving the content on social media.

There is extensive literature on the impact of mainstream media in influencing attitudes to just about everything – and whatever their disagreements, researchers agree that the influence is large. In the COVID-19 pandemic, mainstream media channels are the vehicle for messages from governments about disease spread and recovery, and rules about social distancing, quarantine and testing. This is where we see plans for government actions and subsidies, reports of the pandemic here and overseas, and reports of its impact on the economy and society. There is great uncertainty about how serious COVID-19 is, and how dangerous things really are. With this lack of certainty and our isolation, mainstream media will be even more influential than usual – they are our connection to the rest of the world and everyone is exposed to them.

A case for language

To get an idea of the language used in mainstream media around COVID-19, I picked one exemplar – ABC online headlines. I chose this source because, as the national public broadcaster, the ABC aims (and claims) to be the most trusted news source in Australia. They have had saturation online coverage of COVID-19 since the start of the epidemic, mirroring their television and radio news broadcasting. Their stories contain expert opinion and analysis from epidemiologists modelling the pandemic; doctors and scientists looking at potential prevention, vaccines and treatments; psychologists examining mental health and wellbeing, and economists exploring the large-scale impact of closing the economy. These are embedded alongside human-interest stories on every aspect of the pandemic here and overseas.

I collected ABC online headlines from 7–27 April 2020. This was during the lockdown period and included Easter, Anzac Day and pandemic-related events like the aftermath of the Ruby Princess docking and the illness of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson. It also included the first modelling of the pandemic in Australia and overseas, and tracking of the spread every day. There were 1354 headlines of which 1060 concerned some aspect of the pandemic (including 374 related to social distancing and isolation), and 294 involved other topics.

Some stories were repeated over several days and the judgements about what was COVID-19-related are mine. Nevertheless, they give a sense of how much the pandemic dominated the ABC (and all news) coverage during those weeks. COVID-19 clearly was the news agenda in Australia during April, although other topics achieved greater penetration later in the month (21 headlines on other topics on 27 April versus just two non-COVID-19 headlines on 7 April).

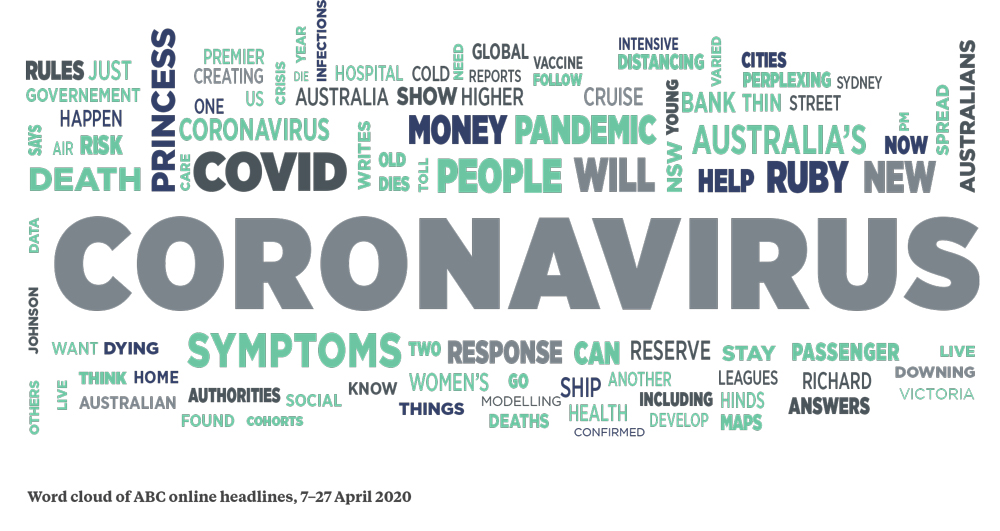

I used word clouds to highlight the key words in the headlines. I created a word cloud every day, and then every week. The one pictured in this article covers the entire three weeks. The word clouds across this period were very stable, with only minor changes in the most common words. Coronavirus was the most prominent word every day, along with COVID, Australia/n/’s, pandemic and global. Words related to health were prominent, including symptoms, death/dying, spread, cruise, ship, Ruby Princess, infections, vaccine and intensive care.

There were common words related to economic and social factors, like money, people, reserve bank, response, distancing, cities, modelling, rules, creating, home. Finally, a number of common words were related to uncertainty – perplexing, rules, need, crisis, government, authorities.

Word clouds allow us to examine sets of associated words. In the word cloud above, you can see a set from the most prominent word, coronavirus, that tells a story about many people being affected by the virus, especially on aeroplanes and cruise ships (landing in Sydney), and high uncertainty. For example, the Ruby Princess docking was referred to for several days as “the Ruby Princess debacle.”

A second set goes from COVID, and is related to the global pandemic and its impact on Australia and on hospitals, death and dying, social distancing. The pandemic was repeatedly described as “dire” and “catastrophic.” The third set goes from death and Princess to talk about the spread of COVID-19, including economic models based on overseas data which were orders of magnitude worse than what actually happened; these were described as “worst case scenarios.” The fourth set also starts with coronavirus, and repeats the impact on hospitals and dying, adding risk and the reactions of politicians (here and overseas) to the mix. There were positive headlines during this period, especially about people’s creativity in lockdown and about the government’s efforts to help people economically, but they were swamped by negative language.

Impact of emotion in headlines

Specific headlines from these three weeks give an emotional tone to the word cloud, and flesh out the impression it creates. For example, the story around the impact of the virus and uncertainty is well illustrated by these headlines:

Why are we so worried about the spread of coronavirus? Think of rice on a chessboard

Aussie nurse Yanti has worked in virus outbreaks before, But what she’s seeing in the US is ‘terrifying’

How the Ruby Princess unravelled

‘It’s bloody awful’: Marie went on the trip of a lifetime, then people started dying

The stories about hospitals, death, and global impact can be seen in these examples:

The second week crash. Why week two as a coronavirus patient is so scary

This is how coronavirus progresses from a dry cough to become a fatal infection in the human body

‘Guilt and shame’ for wearing masks as doctors report widespread sharing

A complete societal breakdown looms if Scott Morrison gets coronavirus wrong

How do we avoid the dreaded second (third or fourth) coronavirus wave?

The impact of the lockdown and social distancing shows up in these examples:

‘We’re so vulnerable’: Solitary outings only or the threat of arrest for these isolated Australians

Tears and fears for landlords and commercial tenants locked in standoff over coronavirus shutdown

Victoria’s ‘bleak and devastating’ economic future laid out in Treasury modelling

‘It’s just horrible’: Scott Morrison gets emotional during interview

‘At the start it was horrible’: Parents reflect on home-school as teachers voice fears about remote learning

Finally, a number of examples of racism and ethnic hostility appeared, although they were not reflected in the most important words – here are some examples:

‘Go home’: Backpackers face stone throwing and abuse amid coronavirus pandemic

Racist coronavirus message sprayed on Chinese-Australian family’s home, rock thrown through window

‘We are all afraid’: Rohingya face growing hostility in Malaysia as coronavirus crisis deepens

Overall, the emotion words were overwhelmingly negative, even when the longer stories were about positive actions. In addition, the headlines often blurred the difference between events in Australia and overseas. Reading them, one gains the strong impression of a globally devastating disease with Australians in great danger, and a sense of vulnerability, fear, sadness and bleakness – and people closing in on themselves and their own groups.

What does this mean for us?

The impression given in the news media should be disturbing to psychology practitioners, teachers and researchers. We need to understand the consequences of behavioural contagion, and as health professionals working with vulnerable people, we need to help reduce it. This means not yielding to the influence of the media on our own emotions and communication. It is as harmful to be a vector of panic transmission as it is to be a vector of disease transmission. Furthermore, panic transmission can be prevented.

Anyone reading the media uncritically is likely to think that COVID-19 is more serious than it is, and that risk is greater than it is. So, in addition to resisting this pressure, it is important to communicate calm, to students and clients as well as friends, family and colleagues. The social-distancing rules are constraining but sensible. Some people over-interpret them to the point that they are anxious about any contact with others. As these rules are relaxed, anxious people need to be encouraged to participate in social contact. They need to understand that although there is some risk, it is very low.

In addition, a better safe than sorry attitude about the pandemic takes focus away from the major economic and social impact – as if any health restriction is worthwhile no matter what the cost. We know this is not so, and we must communicate our own knowledge to those around us. As psychologists, we need to be leaders in the community, and to encourage a more balanced view of the pandemic, including the real risks and health consequences. We need to show resilience and resist the impulse to amplify, via intense and negative emotional language, our own agendas about mental health, family violence or elder abuse. These are important problems, but it would be easy to become panic vectors about them too.

Some are worried about people ignoring social-distancing rules and adopting a cavalier attitude. Such people will not be reached through fear, any more than they have in other health campaigns. They need different strategies that align better with their current beliefs. We need to remember that they are in the minority – the panic-buying of food and the fear-based hostility to other groups show that extreme fear is the more common reaction. We will be more effective if we focus on fear rather than complacency.

What can psychologists do?

We will not get much help from the news media in this regard, so we need to make our voices heard through our own networks, including clients and students. We should read all news media critically. What does the story say? What emotional impression does it give? Is this accurate, and is it appropriate? Does it promote intergroup blaming and hostility? We need to be forthright about our own views, even if this means disagreeing with people around us. We have been flexible and inventive in offering our help to clients and students – now we need to be communicators of calm.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]