Eliciting accounts of highly personal events or situations is a routine part of psychologists’ jobs. In a therapeutic context, clients’ personal stories provide insight to their perspectives on life circumstances and how these change over time. During investigations or assessments, professionals may need to draw out accurate accounts of clients’ events or situations to inform decisions about them. We refer to this latter type of interviewing (the focus of this article) as investigative interviewing.

While there are many factors that define a good investigative interviewer, adherence to non-leading, open-ended questions is paramount. Open-ended questions are the technical building blocks of good interviewing practice. Learning them is as important to communication as learning scales is to creating music. A well-crafted sequence of open-ended questions maximises both the quality of the information garnered and creates a harmonious interaction where people feel connected and valued in the process.

Unfortunately, open-ended questions are not a feature of most investigative interviews. This is true for all professional groups. Widespread evaluation across the globe reveals that, on average, only one in 10 questions is open-ended. Poor open-ended question usage is prevalent even among people who have attended training and who judge themselves to be good interviewers.

Like anything, thinking is not doing. A person can know that open-ended questions are important, and believe they are asking them, without actually doing so (Wright et al., 2007). Training courses can claim to promote good interviewing without actually producing long-term improvement in open-ended questioning.

This article addresses the critical need to improve the quality of our questions on a global scale. It aims to establish greater awareness about what open-ended questions are, their effects, and the type of training needed to master them.

Defining open-ended questions

If an interviewer’s goal is to elicit accurate narrative detail about an event or situation, then open-ended questions must be defined according to two dimensions: first, they encourage an elaborate response, and second, they do not dictate what specific information needs to be recalled.

Common examples of open-ended questions include “Tell me everything that happened”, “What happened next”, “Tell me more about the part where….”, “What happened when…” The words ‘tell me’ and ‘happened’ are helpful, but they are not defining features. The question “tell me everything about what Tom was wearing” is not open-ended because (while it promotes elaborate detail) it dictates what needs to be recalled (a description of clothing). The question “What happened when the phone rang?” is open-ended. While the question includes specific detail, that detail is merely used to elicit a narrative of what happened. The person is free to provide a range of responses from their memory (responses that may or may not be related to the phone call).

Importantly, open-ended questions can be leading or non-leading depending on whether they raise or assume information that has been mentioned by the interviewee before. While non-leading open-ended questions elicit the least error, leading open-ended questions are among the most harmful (Sharman et al., 2020). In other words, interviewers must not only consider the structure of the question; they must also be careful to use the interviewee’s own words and check that any new information they introduce is true before asking the interviewee to respond to questions about it.

Overall, questions requiring a yes or no answer, or questions that ask “Who, What, When, Where, Why or How?” are not generally open-ended. Their focus is on drawing out isolated predetermined details about the event, using a more direct, rapid, question-and-answer approach. Questions that start with ‘explain’ or ‘describe’ are not open-ended if they focus on eliciting descriptive detail as opposed to what actually happened. Descriptive detail can be important, but the focus of narrative recall is the sequence of related activities or actions first and foremost, with contextual details embedded within the actual story (Snow et al., 2009).

Identifying question types may sound tricky, but it can be easily learned with the right training activities. Research has given us a good handle on the types of conceptual errors that people commonly make when trying to craft good open-ended questions, and how to best sequence a series of these questions to maximise accurate and coherent detail (Powell et al., 2013a; Powell & Snow, 2007; Powell & Guadagno, 2008).

Like practising musical scales, rote learning of different question types may not be the most enjoyable task, but it is nonetheless an essential prerequisite to becoming a good interviewer (Yii et al., 2004).

The effects of this questioning style

One of the main reasons open-ended questions are not frequently used is that they are not easy questions to respond to, especially for vulnerable interviewees with language or cognitive impairments (Wright & Powell, 2006). Although interviewees of all developmental stages feel more active and valued in the interview process when they are asked open-ended questions, responding to these questions requires intentional effort (Brubacher et al., 2019).

Memory details must first be recalled and then structured into a story format that can be understood by a naive listener. In contrast, when specific cues are included within the form of a focused question, responses are more rapid and made on the basis of familiarity (Ibabe & Sporer, 2004). With forced choice or yes/no questions, for example, the interviewee merely needs to recognise whether the detail suggested is correct. These questions don’t involve recall of information at all.

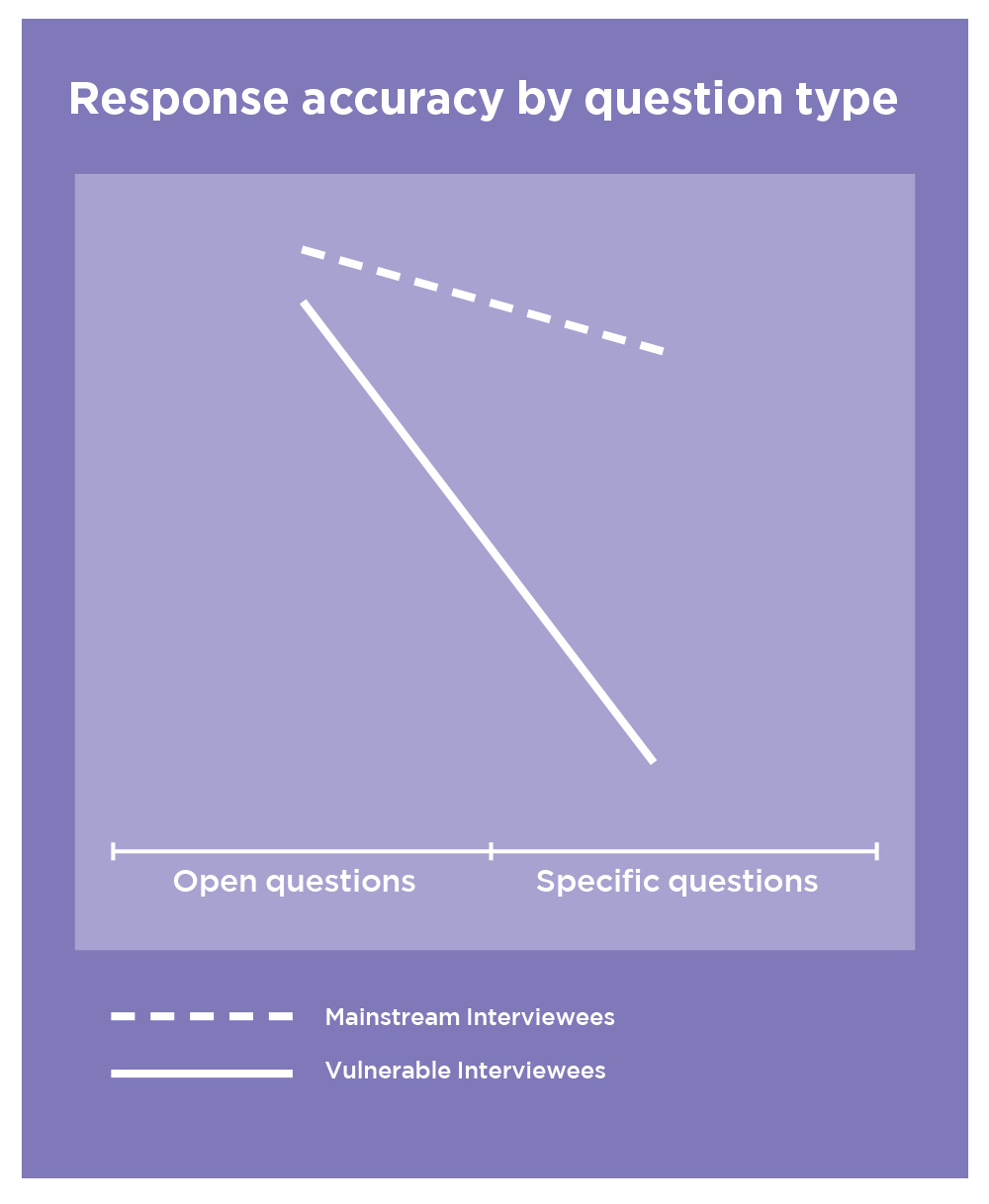

Being easy to answer does not make a question better. One of the most robust findings in human memory research is that open-ended questions elicit the most accurate responses (Sutherland & Hayne, 2001). This is because having time to collect one’s thoughts and to mentally reconstruct the event in their minds promotes elaborate memory retrieval and gives interviewees the control or scope to report what they remember. As the figure shows, the benefit of this deeper level of memory processing on response accuracy is even more pronounced for people who are vulnerable for language or cognitive reasons. The very people who find it hardest to respond to open-ended questions are the people who are more prone to error when they are not asked these questions (Agnew & Powell, 2004).

Unfortunately, the damage caused by avoiding open-ended questions cannot usually be undone, as most errors arising from “Wh” or closed questions are unintentional. Human memory is not designed to work like a camera. Reconstruction of events (due to forgetting or inattention to certain details and later filling the gaps in our memory) is normal. These normal memory errors are minimised when we (as interviewers) minimise questions that introduce or request specific details that may not be in the person’s memory store (Powell et al., 2013b). Errors can also be social rather than memory related (e.g., guessing an answer or agreeing with a suggestion merely to comply with the interviewer, appear competent or get the interview over with quickly).

Considerable patience on the part of the interviewer is required to let the interviewee respond in their own time and the best way they can. A good analogy is the Aesop fable where the impatient farmer killed the goose that laid the golden eggs. An interviewee (like the bird) can only provide rich responses when handled with understanding, consideration and care. Short-sighted and persistent attempts to elicit highly specific details quickly can risk losing everything, if the desired outcome of the interview is a fair decision based on accurate detail. Consider for example, the prosecution of sexual assault which is highly dependent on verbal evidence from witnesses. Research suggests that insufficient open-ended questioning is contributing to low prosecution and conviction rates. Specific questioning focused around unnecessary minutiae details heightens inconsistencies or errors that are then used under cross examination to shed doubt on the reliability of the interviewee’s entire account (Pichler et al., 2020).

The good news is that all people, including children as young as four years of age and adults with communication impairment (e.g., those with three- to five-word sentences) are capable of responding to open-ended questions with informative detail (Bearman et al., 2019). And as with anything, practice with this style of questioning helps people become better at responding. Although interviewees’ initial responses to open-ended questions may be brief and lacking in detail, gentle persistence with these questions (particularly those that use prior responses as cues for further information) can often result in extensive or contextually elaborate accounts, if interviewees are given sufficient time and support.

Not all open-ended questions are equivalent in their effectiveness at eliciting narrative detail. The best open-ended questions are those that steer the interviewee to relevant aspects, minimise defensiveness and anxiety, overcome people’s natural tendency to suppress information, avoid raising information that has not yet been established, and encourage coherency and elaborate detail. Interviewing is best conducted in a supportive, distraction-free environment where the interviewer’s questions and behaviour emphasise the interviewee’s capabilities and role as informant. Ideal questions (irrespective of whether they are open-ended) are those that: are non-leading, allow flexibility in the response, are simply phrased, and target concepts that are appropriate for the developmental level of the interviewee. Ideal behaviours that accompany these questions are those that: show the interviewee that (s)he is being heard, understood and not judged, show faith in the interviewee’s ability to competently communicate, and are accepting of any response – even “I don’t know”.

A final advantage of using open-ended questions is that they put less cognitive strain on the interviewer who is then available to listen to, understand and fully engage with the interviewee as opposed to constantly thinking about the next question.

How open-ended questions are learned

Using open-ended questions is a practical skill and with any practical skill, behaviour cannot change from reading papers or instruction alone. Changing people’s questioning behaviour in a sustainable way is a complex area of science, where the cornerstones of an ideal training program include ongoing practice, individual and immediate expert feedback, exemplars of best practice, and quality control evaluation (Lamb, 2016). Effective training courses need not be long, or require the expenses associated with travel and accommodation. But if the science underpinning human learning is ignored then the training will not likely work.

Many existing interviewer training courses are based around a typical one-teacher classroom model where a herd of people learn in lockstep over a single period of time (Westera et al., in press). Even in situations where this instructor is an experienced topic expert and excellent teacher, the evaluation research suggests that this model is completely ineffective. Learning to be a good interviewer involves many sub-skills which need to be taught in a certain order and at people’s own pace (Powell, 2008).

Some of the steps include understanding various questions and their effects, rote learning of question stems, understanding and practising how to choose the most effective questions in various situations and with different types of interviewees, and knowing how to introduce prior information while minimising error. Teaching exercises need to be engaging and tailored to the sub-skill being taught. Because question types are static facts and concepts, this aspect can be effectively taught with electronic quizzes where expert feedback is instantaneous, and knowledge regularly assessed.

Rote learning can be done individually or in groups but needs to be spaced over time and across varied contexts. Understanding how to deal with complex work cases is best addressed through group discussions in person or via videoconference (or film). More strategic knowledge around choosing and using a variety of open-ended questions is best learned with a trained actor who plays the role of the interviewee in a controlled environment designed to emulate real-world situations (Powell et al., 2008). We refer to these as mock interviews.

Mock interviews with trained actors are the most valuable and resource-intense component of training, and the focus of considerable ongoing research. The benefit of mock interviews is multifaceted. They provide standardised measures of performance, and opportunities to practise choosing questions in increasingly challenging contexts. They are also a valuable source of feedback as trainee interviewers get to observe the impact of questions on responses.

If you think of the task of adhering to non-leading open-ended questions as walking a plank, a good actor’s job is to wobble that plank and tempt you to ask less desirable questions. If the actor’s wobbling technique is underpinned by a good scientific knowledge of the sort of precipitating factors that knock people off that plank in the field (e.g., uncomfortable pauses, irrelevant or opaque responses) then your ability to stay on the plank will likely improve over time and transfer to the field.

Such acting is not usually done by professional stage or screen actors, but rather assistant trainers who can follow instructions (stick to their rules), who have sufficient content knowledge to provide effective feedback, and the flexibility in their schedule to be available for trainees on an as-needed basis. Trainee interviewees do not need to understand all the complexity surrounding how courses are built. But if they want to gain practical skills, they should ensure that the course developers they choose are across the issues. The only way to know is to ask for and seek objective evidence that the training program has produced sustained adherence to open-ended questions in the long term (Benson & Powell, 2005).

Testimonials and qualitative feedback are not good indicators. The hallmarks of a good evaluation include objective measures of questions and question coders with demonstrated inter-rater reliability; and evaluation results that have included long-term follow up, are publicly available, and have undergone independent (anonymous) peer review.

Improving the practice

Many people think that open-ended questions are not very effective. But that’s not true. With sufficient training, and the support to let people tell what happened in their own way, we can vastly improve the quality of information elicited and the client’s perception of feeling listened to, understood and not judged. All people recalling highly sensitive information deserve to have good questioners, and all interviewers in turn deserve the quality of training that this complex skill requires.

For resources on best-practice interviewing of vulnerable witnesses, refer to:www.investigativecentre.com/resources

The author can be contacted at [email protected]