As part of Psychology Week 2018 the APS and Swinburne University produced ‘The Australian Loneliness Report’, based on a national survey of adults. The survey examined the prevalence of loneliness and how it affects the physical and mental health of Australians.

Survey overview

A sample of Australian adults (n = 1678) completed an online survey about their wellbeing. The sample comprised a nationally representative sample (n = 570), supplemented with recruitment by the research partner networks, community organisations, social media and advertising. The data was collected over a period of four months, from 29 May to 1 October 2018. The key findings from the data collected for the first time point are summarised in this article.

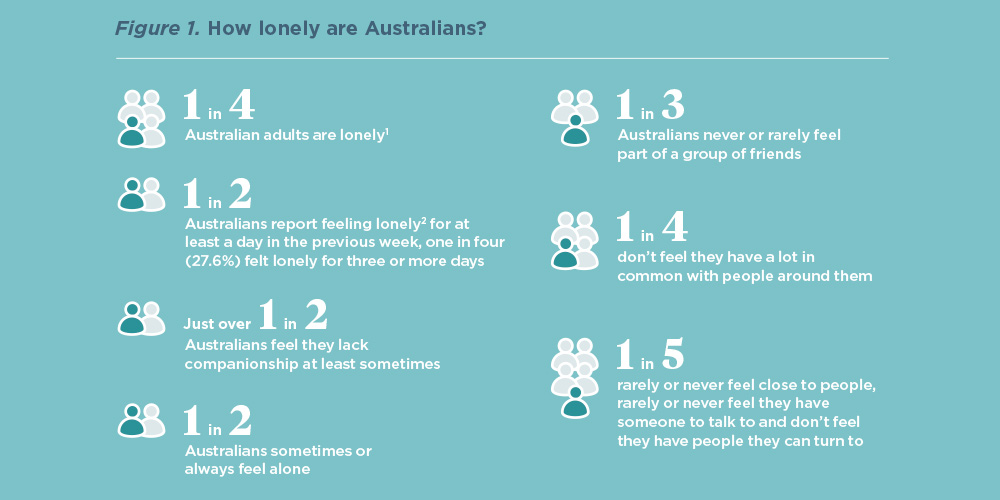

How lonely are Australians?

A single-item measure of loneliness may not provide a comprehensive assessment, hence loneliness was measured using the 20-item psychometrically validated UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Loneliness Scale – Version 3 (UCLA-LS, Russell, 1996). Based on a cut off score on this measure of 52 or more1 (score range 20-80) one in four (26.9%) Australian adults are lonely. When directly asked, using a one item loneliness measure2, one in two Australians (50.5%) reported feeling lonely at least one day in the previous week, while one in four (27.6%) reported feeling lonely for three or more days (see Figure 1).

Those Australians who were married were the least lonely, compared with those who were single, separated, or divorced. Australians in a defacto relationship were also less lonely than those who were single or divorced. Interestingly, no age group was lonelier than other age groups. Contrary to what is commonly reported (e.g., Valtorta, 2012), in this survey, older adults over 65 years were found to be significantly less lonely than younger adults.3

There are several study limitations that may have influenced results. First, there was an underrepresentation of adults aged 76 and over (n=35) and so they were included in a broader older adult category of over 65 years. Second, the methodology of using an online survey may mean that those who participated had access to the internet, and therefore may be better connected to services. A pen-and-paper survey may capture less well-connected individuals and influence loneliness scores.

These findings however are consistent with previous APS Psychology Week surveys, including the 2016 survey which found that older Australians reported significantly higher levels of wellbeing and lower levels of loneliness and negative emotions than the rest of the population (APS, 2016). In this year’s survey, Australians over 65 were also found to have better psychological wellbeing, less social interaction anxiety, fewer depressive symptoms, reported better physical health, and greater social interaction than younger Australians.

How does loneliness affect health?

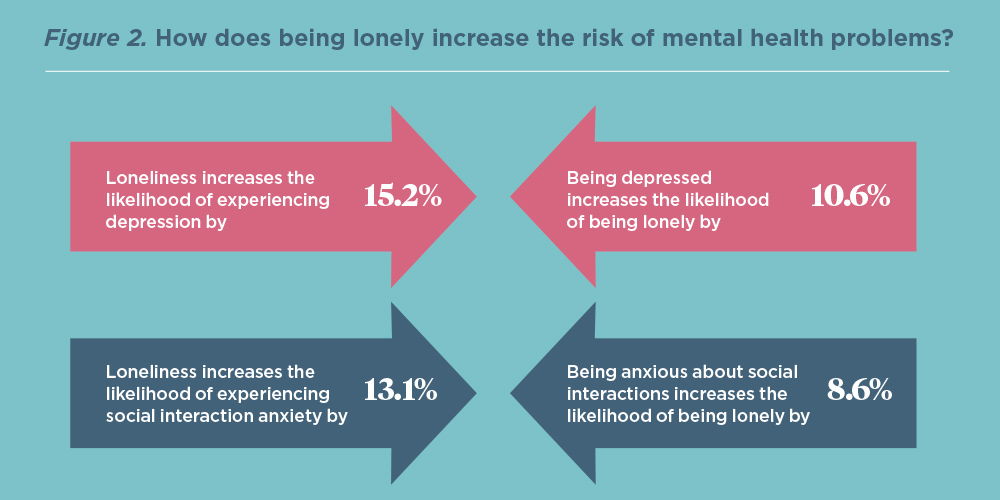

Australians reporting higher levels of loneliness (i.e., those who scored 52 or more on the UCLA-LS) were found to have significantly poorer mental and physical health than less lonely Australians. The impact on mental health is substantial, as shown by Figure 2. Loneliness increases the chance of being depressed or anxious about social interactions, and experiencing depression and social interaction anxiety also increases the chance of being lonely. This is consistent with other research highlighting the strong relationship between loneliness and both social anxiety and depression (Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur & Gleeson, 2016).

The impact of loneliness on poorer physical health outcomes was demonstrated via poorer sleep, more headache symptoms, increased stomach complaints and more frequent respiratory infections. This is also consistent with previous research (Holt-Lunstad, 2018), and highlights the widespread effect of loneliness on physical health.

These experiences of physical and mental ill health may cause an individual to withdraw from social interactions, making it more difficult for them to overcome loneliness.

Making the connection

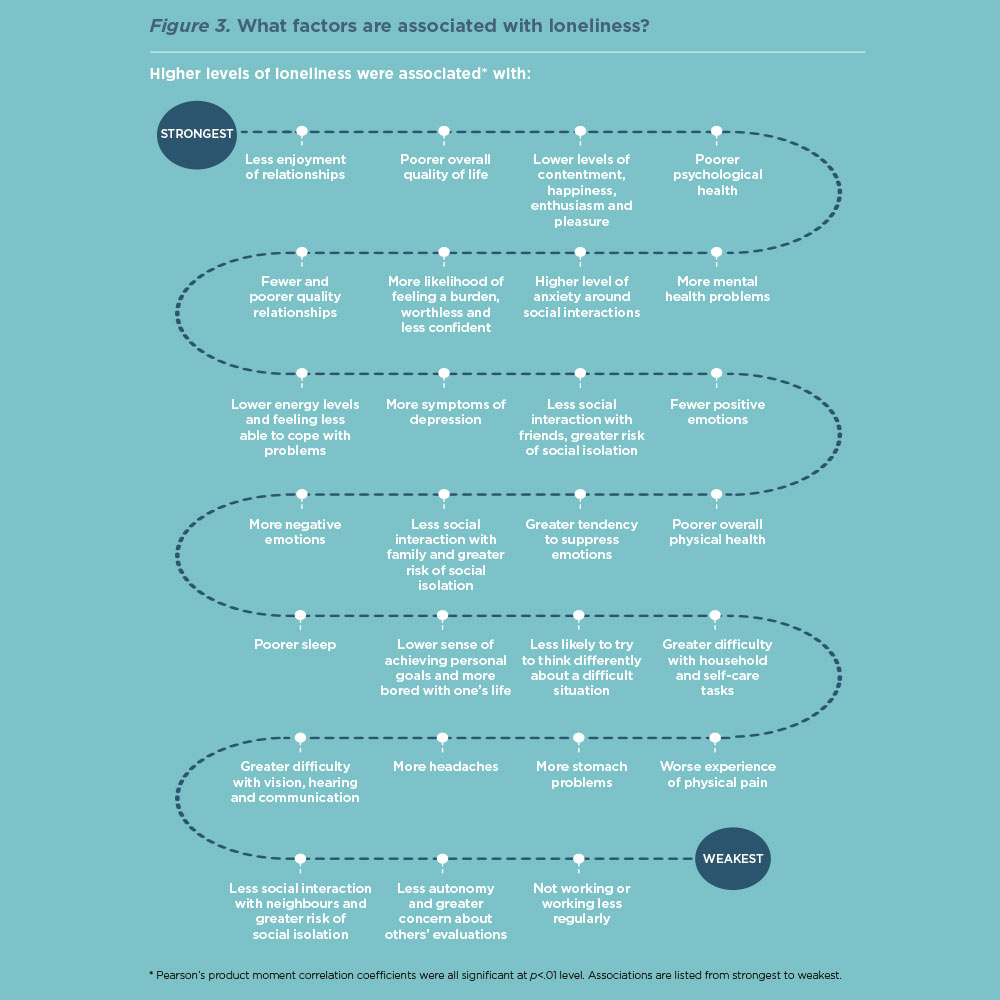

There was a significant relationship between loneliness and all the measures assessed by the online survey (see Figure 3). These relationships further emphasise the strong impact of loneliness on mental, physical, and social wellbeing. However, they also provide insight into protective factors and highlight priorities for treatment. For example, loneliness interventions could assist individuals to experience more positive emotions and greater self-worth, engage in pleasurable and engaging activities and assist with challenging unhelpful thoughts and beliefs (e.g., “I am worthless”).

Survey implications

This national survey highlights the urgent need for policy and interventions that target loneliness. Australian Government funding has so far targeted older adults, but our survey has highlighted the need to address loneliness across the adult lifespan.

Psychologists need to ensure that they identify loneliness and assess for co-occurring social anxiety which may contribute to loneliness severity. Interventions need to be refined, modified, and delivered based on the complexity of loneliness.

The full report of the survey is available from the Psychology Week 2018 campaign website: psychweek.org.au