Psychological treatment has long been recognised as effective with a distressed individual who receives therapy being better off than 80 per cent of distressed people who do not (Wampold & Imel, 2015). However, when we dig deeper, these often-cited results reveal an uncomfortable truth. On average, 5–10 per cent of clients a psychologist sees will reliably deteriorate and 35–40 per cent of clients will experience no change in distress (Hansen et al., 2002).

Within that average, psychologists vary significantly in their effectiveness as demonstrated in research by Okiishi and colleagues who investigated the outcomes of 71 therapists who treated clients with equivalent levels of initial severity. Results of the top performing 10 per cent of therapists had a client improvement rate of 44 per cent and a client deterioration rate of five per cent. In stark contrast, the least performing 10 per cent of therapists had a client improvement rate of 28 per cent and a client deterioration rate of 11 per cent (Okiishi et al., 2003, 2006).

These results are particularly relevant in the field of psychology in Australia with stakeholders participating in the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System recommending routine outcome measurement in mental health to evaluate treatment effectiveness (State of Victoria, 2019). Regardless of whether this practice becomes widely adopted across Australia, providing effective service remains a central part of client care. Poor awareness of our own effectiveness is a core barrier to this.

Evaluating treatments

To evaluate our treatment effectiveness, we must first set up a system of routinely gathering client demographic information and outcome measurement data. The outcome measurement data gathered will depend on the values of the psychologist and the clients they serve (e.g., wellbeing, distress and functional outcomes).

The second step is to consider how we want to answer the question of how effective our treatment is. Anchoring this by also considering how a client themselves would ask this question is beneficial. For example, we’ve all had questions from clients like:

1. How effective is your treatment?

2. How many people who come for treatment with you get better?

3. How effective is your treatment with my particular/specific concern(s)?

These questions can all be answered clearly and concisely by evaluating one’s practice, using Cohen’s d, Reliable Change, and Clinically Significant Change analyses respectively.

Ideally, we are then able to use this information to improve psychological services for clients and referrers. One way to use evaluation results to improve psychological services is to focus on increasing client confidence, improving cost-effectiveness of training and creating an outcome-based niche.

Increasing client confidence

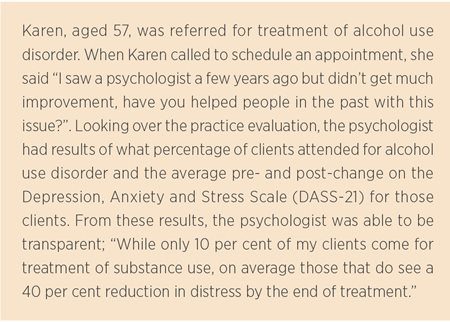

Providing education to clients about the effectiveness of your treatment and openly discussing which client groups and presentations you are most or least effective with can increase client confidence. Using outcome data to guide these transparent conversations is not only ethical, but also creates trust with clients and increases their confidence in the treatment offered.

Improving cost-effectiveness of training

Awareness of knowing the clients or presentations you are least effective with allows your professional development goals to be more targeted. By attending training(s) that directly addresses your clinical pitfalls (and all psychologists have them), these areas are strengthened, improving overall treatment effectiveness. As a bonus, continuing professional development (CPD) becomes more cost-effective as hard-earned money is no longer spent on training that is already a strength for the psychologist.

Creating an outcome-based niche

An outcome-based niche describes identifying the presenting issue(s) for which you achieve the most effective treatment and making this known so clients with the same issue can find you. While this does not guarantee that everyone presenting with this niche issue/presentation will get the most effective treatment, it improves the probability of a desirable outcome. This is in opposition to how niches are typically developed, where a clinician decides based on their interest, research or experience. None of these factors increases the likelihood of effective treatment for new clients. Knowing what client presentation(s) you treat most effectively, allows you to discuss this with your referrers. This reinforces further referrals for clients with similar presenting problems and increases the likelihood of more individuals accessing effective treatment.

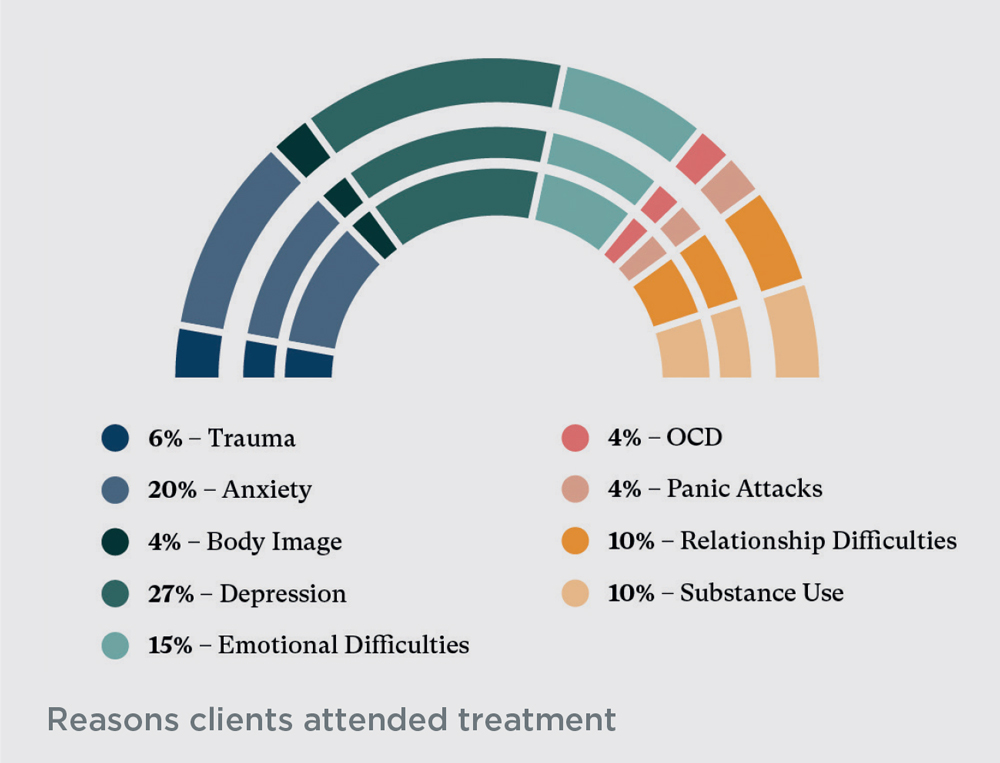

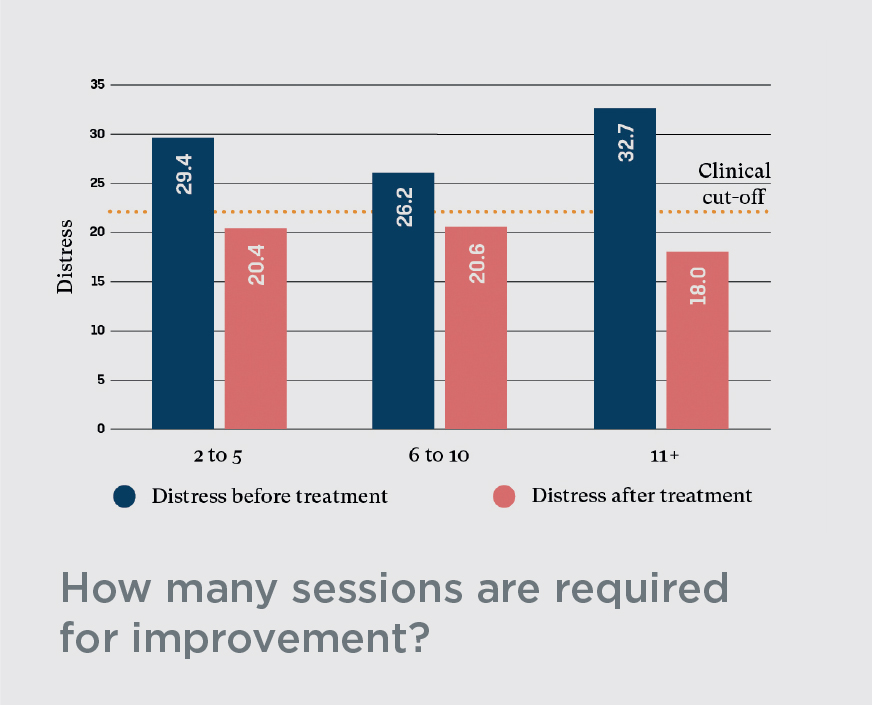

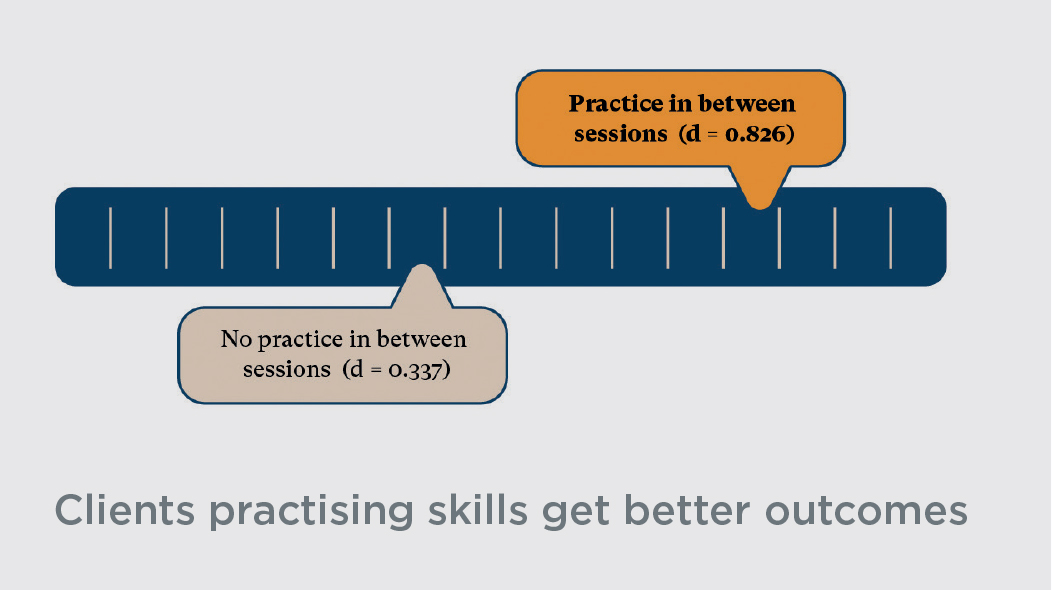

An example of a practice evaluation can be seen in the author’s data visualisation of psychology outcomes. This visual summary shows the results of an evaluation of client outcomes across 2017–2019 in a private practice setting. It answers some relevant questions about client presenting concerns, average treatment effectiveness, and reliable improvement rates. It also answers specific questions that are of value to many clients and referrers relating to drop-out, how many sessions are required for distress reduction, and elements of treatment that are associated with better outcomes. The immediate benefits of this practice evaluation summary can be seen for any clients trying to decide which psychologist may be the best fit for them.

The comprehensive practice evaluation which this summary was based on also has long-term benefits in that the results can easily answer key questions from clients or referrers. The comprehensive practice evaluation also highlights the clinical weaknesses for the author, which has created a roadmap for future CPD to strengthen these clinical skills. As further outcome data is gained and evaluated by this method, an outcome-based niche is beginning to emerge. A larger sample size is needed to confidently state an outcome-based niche; however, the journey is as informative as the destination.

While practice evaluations do not guarantee effective individual outcomes or allow us to predict exactly how a particular client will respond to treatment, they provide a guide to whether psychologists provide effective treatment, for whom, and in what context. This is an important strategy to improve psychological services by increasing client confidence, improving cost-effectiveness of training, and creating an outcome-based niche. Our clients show us their growth and change every day, so lets follow their lead.

The evaluation method used is freely available, please contact the author by email for the evaluation method.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]