Neurological disorders are disorders of the brain and nervous system, such as epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and acquired brain injury. Almost one in six people worldwide have a neurological disorder, and prevalence will rise as the population ages (WHO, 2006). So it is very likely that you will work with people with these disorders at some stage in your psychology career. Two of the most common psychological comorbidities experienced across neurological disorders are poor mental health (e.g., depression and anxiety) and poor cognitive function (e.g., inattention, poor memory) (Gandy et al., 2018; Hesdorffer, 2016). These psychological comorbidities are reciprocal risk factors for each other, and may complicate traditional psychological treatment approaches.

The good news is, with some tailoring, psychological treatments can play an important role in assisting people with neurological disorders manage psychological comorbidities. They can also help assist people with the general self-management of their disorders, such as adjusting to functional limitations, adhering to treatments and modifying lifestyles known to exacerbate neurological symptoms.

Neurological disorders are currently incurable and can affect almost all aspects of a person’s functioning including vision, language, emotion, cognition and movement. As such, they require ongoing self-management and can result in significant disability and poor quality of life.

This article outlines tips for working with people with neurological disorders and suggestions for tailoring psychological treatments to be most helpful. These issues are mainly discussed in the context of skills-based psychological treatment approaches, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

Tip 1: Integrate neurological symptoms into your formulations

Neurological disorders can have a significant impact on the brain and result in many challenging symptoms. This includes, but is not limited to, symptoms in the domains of:

- attention/memory

- insight

- organisation/planning

- sensation/perception

- movement/coordination

- energy/sleep-wake cycles

Not all people with a neurological disorder have difficulties in all these areas. And, no two people experience the same difficulties. However, for most people, neurological symptoms will play a role in the development and maintenance of poor wellbeing and mental health difficulties.

Most clinicians are very familiar with the basic premise of a CBT formulation, which highlights the role and cycles between the three factors of:

1. Unhelpful thoughts (i.e., how we think about things)

2. Physical symptoms (i.e., what our bodies are doing)

3. Unhelpful behaviours (i.e., things we do or don’t do)

For many people a fourth factor that can be introduced into this model is:

4. Neurological symptoms (i.e., difficulties due to the disorder).

This is because neurological symptoms can impact the other three factors and contribute to vicious cycles of symptoms, known to contribute to poor wellbeing and mental health difficulties. For instance, some neurological disorders can impact parts of the brain which help with emotion regulation and thinking. While, other disorders can result in physical restrictions and limited mobility.

People with neurological disorders tend to respond well to this modified model/formulation (see diagram of the tailored CBT model) as it (1) normalises their challenges and experiences and (2) validates the additional challenges they face with their health and wellbeing.

This modified model can also start to give the clinician an appreciation of why untailored psychotherapy or CBT in this area may not be as helpful, and provide some ideas of how therapy may require tailoring.

The role of psychological treatment is not to treat these neurological symptoms per se but to help people understand their role in their wellbeing and learn to manage the impact they have. Thus, one helpful way of discussing the role of neurological symptoms is to frame them as ‘problems’ and how these problems can impact their wellbeing and make their other symptoms harder to manage.

It can be useful to point out that neurological symptoms can impact wellbeing by:

- creating significant problems in the lives of people with neurological disorders. Some are often caused directly by neurological symptoms (e.g., problems with concentration) while others can be more indirect and general in nature (e.g., employment challenges, driving restrictions).

- affecting their ability to solve problems. This can be because of problems with:

- slowed thinking

- getting stuck on certain ideas (i.e., rigidity)

- having difficulty making a decision

- depression and anxiety.

For these reasons teaching structured problem-solving skills can be very helpful (see Tip 3).

Tip 2: Assess for cognitive problems

If you are used to assessing and treating mental health issues you may be less used to assessing for cognitive difficulties. This is sometimes seen as the realm of clinical neuropsychology not clinical psychology. However, there are three important reasons for also asking about these issues in people with neurological disorders:

1. For many people cognitive difficulties will be impacting their mental health and functioning – and vice versa. Thus, they often play an essential role in one’s formulation.

2. Cognitive difficulties may get in the way of learning, retaining and practising therapeutic information and skills. Thus, you may need to modify your therapeutic style and make provisions to assist with these things.

3. Psychologists are in a unique position to teach skills to help people manage cognitive difficulties.

If the person has had a neuropsychological test done it can be helpful to ask for a copy of the report or do the test yourself. However, sometimes these assessments are very technical and it is important to check in with them about how they perceive their cognitive difficulties and their impact on daily functioning. Again, a good non-intrusive or minimally offensive way to do this is to frame the issue of cognitive difficulties/impairment as ‘cognitive problems’. For instance, some helpful questions may be:

- Do you experience problems with your thinking, memory, attention?

- How do these cognitive problems impact you day-to-day? For instance, do you experience problems forgetting what you’ve done? Problems paying attention?

- Do you have any concerns/worries about your cognitive problems getting in the way of therapy?

Of course, there will be some people, such as those with a brain injury, who may have limited insight into these problems. However, you may start to get a sense of these problems yourself during sessions and may find it helpful to have an appointment with a family member.

Tip 3: Teach structured problem-solving skills

Structured problem-solving can be a really helpful skill and therapeutic framework for introducing additional coping skills to people with neurological disorders. In many ways problem-solving forms the basis of ‘rehabilitation’ (as defined by the WHO as interventions needed when a person is experiencing or is likely to experience limitations in everyday functioning [WHO, n.d]). For instance, occupational therapists are expert in problem-solving physical and functional limitations which can often assist with cognitive and mental health difficulties.

Problem-solving can be particularly helpful when a person has a neurodegenerative disease, like Parkinson’s disease or progressive multiple sclerosis, where their symptoms will get worse over time or a disorder where symptoms change often and unexpectedly.

Structured problem-solving can be introduced as a means of both (1) finding solutions for problems, where possible and (2) finding ways of coping with problems, where there is no solution.

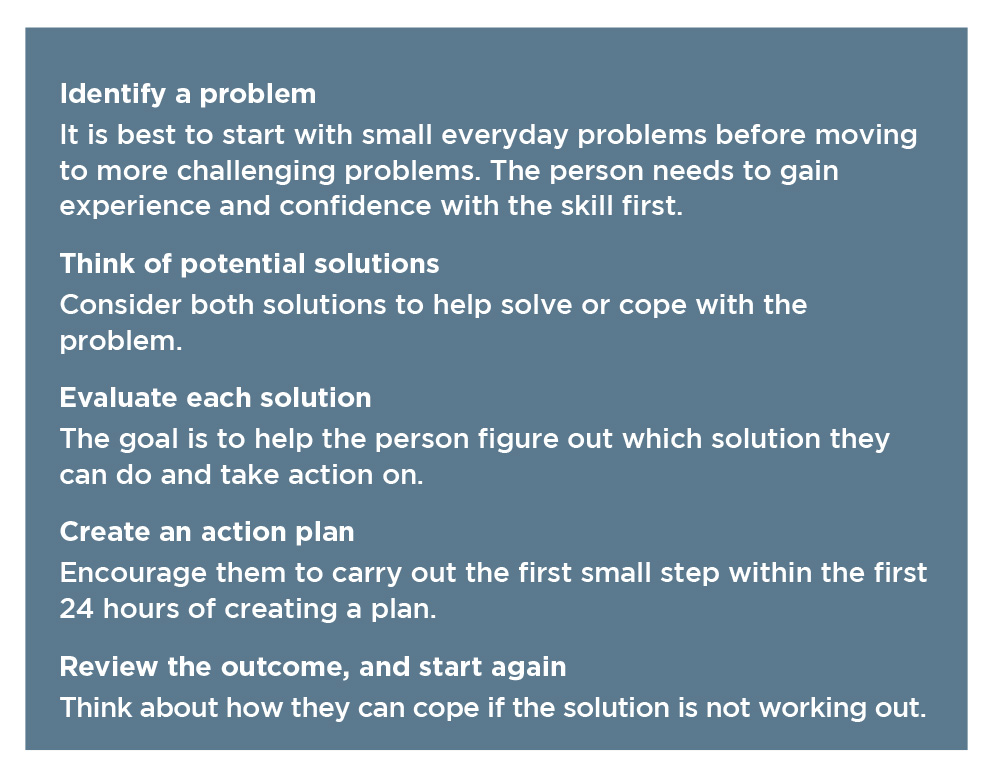

They key to teaching problem-solving is do it in a structured way. For instance, most structured problem-solving will teach people to use the following basic steps.

Tip 4: Become familiar with compensatory cognitive rehabilitation skills

There has been growing interest in cognitive rehabilitation programs which aim to improve cognitive functioning. Two core approaches have emerged;

1. Restorative i.e., approaches that focus on improving specific cognitive skills through the repetitive practice of specific cognitive exercises or extensive drills, such as the Stroop task.

2. Compensatory i.e., approaches that aim to teach pragmatic self-management strategies for maximising cognitive functioning or getting around cognitive difficulties.

The research into the effectiveness of these approaches is ongoing. However, compensatory skills-based approaches appear to be acceptable to people and may have more day-to-day practical appeal for reducing cognitive complaints and improving functional outcomes (Radford et al., 2012; Velikonja et al., 2014).

Psychologists working with people with neurological disorders should become familiar with the basics of compensatory cognitive rehabilitation skills, even if the person is presenting primarily for help around mental health difficulties. There are two broad ways of classifying these skills:

1. Internal skills, i.e., which the person does in their mind internally (e.g., mnemonics)

2. External skills, i.e., which involve outsourcing the demands on one’s cognition (e.g., using diaries or recording devices) or manipulating things externally in the environment or (e.g., reducing distractions).

There are many compensatory cognitive skills out there and some of them are very technical (e.g., method of loci). Instead of bombarding people with every possible strategy, it is most helpful to use a problem-solving solution focus to select the most appropriate skills to solve or compensate for specific cognitive problems. These problems may even be impacting their ability to take part in or get the most out of therapy (e.g., if they miss appointments, cannot concentrate for long periods of time, forget what is covered, are very tangential).

As an example, a common problem experienced by many people is forgetting to do things. For some people with neurological disorders this can be a daily experience and can impact important things like forgetting to take medications, attending appointments, important dates or routine tasks. Below are some examples of compensatory cognitive rehabilitation skills you could consider covering to help people tackle the common problem of forgetting to do things:

- getting organised, assisting with establishing routines

- using alarms and reminders

- using planners (e.g., diary, journal) something that they can carry at all times and make notes in

- linking new tasks with routines (e.g., checking planner with morning coffee).

Tip 5: Tailor thought challenging

Thought challenging is a helpful skills for everyone. But, it can sometimes be taught in an insensitive or unrealistic way to people experiencing very real and challenging situations.

Some of us may have been trained to teach peoples to challenge the reality of thoughts (e.g., “how realistic is that thought?” or “what is the evidence for X?”). However, in reality many people with neurological disorders face very challenging situations and symptoms. In fact, they often have a lot of evidence that their thoughts (e.g., “my condition will only get worse”, “people will discriminate against me because of my disorder”) are true!

It can be far more helpful to teach people to challenge the helpfulness as opposed to the reality of thoughts and to problem solve around their difficulties. For instance, key thought challenging questions may be “is this thought helpful?” or “is this thought stopping me from doing something that may help?”

In general, caution is needed to avoid people thinking thought challenging is ‘positive thinking’ or a simple skill to use. Early on it can be useful to frame thought challenging as a skill that may work by preventing making mood or situations from getting worse, as opposed to leading to improvements in symptoms. It is important to let people know thought challenging is a tricky skill that takes time and practice to be most helpful.

Another principle for teaching thought challenging, in particular to people with neurological disorders, is to keep it simple. It is amazing how complicated thought challenging can be, with some handouts having 20 different ways of challenging thoughts. Most clinicians struggle to remember and utilise all of these questions.

So, it may be unrealistic to think that others will find these things practical, and a good chance they will find them overwhelming. A great example of a simple, but effective, way of doing thought challenging is using the THINK acronym. This was introduced to me by a person with a brain injury, who took part in an online psychological intervention I was running. His THINK acronym, which he saved on his phone and revised often, involved challenging his thoughts by asking “Is this Thought ….. True? Helpful? Inspiring? Necessary? or Kind?”

Tip 6: Consider cognitive activity scheduling

Activity scheduling of light pleasant and physical activities is a commonly used skill to tackle under-arousal associated with low mood and depression. There is also ongoing research into the role of keeping cognitively active on our brain health (Kivipelto et al., 2018 ). There are some suggestions that remaining cognitively active may help prevent or slow down cognitive decline. Thus, for some people it may be helpful to consider using activity scheduling as a way of gently increasing light cognitive activities (e.g., doing puzzles, reading, playing memory games, learning a new language).

Tip 7: Activity pacing in an important skill

Many people with neurological disorders end up in an overdoing-underdoing cycle, which involves the following stages:

- Doing as much as possible (overdoing it) when neurological symptoms are less or because of unrealistic expectations. This can then cause an increase in symptoms – e.g., fatigue, poor concentration, slowed thinking, exhaustion.

- Then doing very little and resting a lot (underdoing it) because symptoms are made worse.

- Then once their symptoms have reduced, they start trying to ‘catch up’ and start ‘doing as much as possible’ again, which then keeps the cycle going…

The ‘overdoing-underdoing activity cycle’ is a big risk factor for fluctuating symptoms and poor wellbeing. But, very few people are taught about it and many well-meaning people fall into this cycle. It is important to look out for this cycle in people you work with and to teach them about it.

When it comes to tackling the overdoing-underdoing activity cycle, activity pacing is a very helpful skill. It involves teaching people how to find a consistent level of daily activity that they can maintain without making neurological symptoms worse.

Activity pacing can be applied to:

- physical activities (e.g., walking, standing, lifting, cooking, cleaning, long commutes).

- cognitive activities (e.g., typing, reading, talking to people, watching TV, completing forms)

- a combination of physical/cognitive activities (e.g., attending work meetings, family gatherings, driving).

It is worth becoming familiar with the skills of activity pacing when working with people with neurological disorders. Some basic tips for introducing this skill include teaching people to:

- break activities up into smaller more manageable parts

- schedule in regular breaks (e.g., sitting down, listening to music, having a cup of tea)

- regularly switch between activities (e.g., alternate between standing and sitting at your desk or between reading and stretching).

Tip 8: Think critically about unhelpful behaviours

- Many people with neurological disorders will be doing things, which on the surface may look like unhelpful safety behaviours, but are in fact minimising risks and flare-ups in their neurological symptoms. For instance, it is not uncommon to work with people who are:

- prescribed diazepam to take when they notice symptoms of panic to prevent a flare-up in neurological symptoms, such as seizures

- prescribed naps by their neurologist to tackle neurological fatigue and overstimulation

- avoiding certain stimuli to prevent overstimulation of the brain or cognitive overload. For instance, in public someone with a brain injury may wear dark glasses, earplugs and avoid crowds.

From a purely general mental health perspective these things may raise alarm bells as unhelpful or maintenance behaviours. However, it is important to distinguish whether they are indeed helpful from a neurological perspective. If possible it can be helpful to check in with the person’s general practitioner or neurologist about these things, and ask whether there is anything that people should not be doing from a safety perspective.

From a purely general mental health perspective these things may raise alarm bells as unhelpful or maintenance behaviours. However, it is important to distinguish whether they are indeed helpful from a neurological perspective. If possible it can be helpful to check in with the person’s general practitioner or neurologist about these things, and ask whether there is anything that people should not be doing from a safety perspective.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]

Further resources

- CogSMART: Cognitive Symptom Management and Rehabilitation Therapy (cogsmart.com/resources)

- Australasian Society of the Study of Brain Impairment (www.assbi.com.au)

- A free internet-delivered psychological treatment program for adults with neurological disorders, known as the Wellbeing Neuro Course is available at the Macquarie University eCentreClinic. This course aims to teach skills to manage emotional and cognitive wellbeing and is currently offered as part of a clinical trial (ecentreclinic.org/?q=WBNCourse)