Nothing can prepare someone for the transformation that happens during the perinatal period. The perinatal phase is more commonly defined as conception to the end of the first postnatal year. Despite being a relatively brief period in an individual’s life, it can hold some of the greatest impacts for the individual, infant and family system. Waqas et al (2022) comment that perinatal mental health difficulties, “pose a global health concern due to their high prevalence and adverse maternal and child consequences”. Suicide continues to be reported as one of the leading indirect causes of maternal death, (RANZCP, 2021, pg3). It is estimated that perinatal mental health costs $877 million annually in Australia (GFA, 2019). This cost is likely to have increased post-pandemic with mental ill health continuing to be a significant public health issue (Kohlhoff et al, 2022).

The development of the perinatal field

This area covers the intersect of physical and mental health. For the psychologist it is a challenging field that requires knowledge about not only physical, emotional and diagnostic issues but the associated skill set for treatment during this period of unique risk to expectant and new parents.

The birth process has only been recognised as having both a physical and psychological component since the beginning of the last century. The psychological process of becoming a mother has been more widely recognised recently as a period called “matrescence” (Raphael, 1975). Prior to this, there was very little information about such a transformative time for those involved.

Throughout the past century perinatal processes and procedures have changed with shifts towards more medicalised processes, back to midwife-led care in the 1960s then to the current status quo. Nationally we are moving towards a more medical model once more with rates of induction, caesarean section and medical interventions increasing. Yet Michaels (2018) has found that although this has decreased the mortality rate for mother and baby, it has not decreased the psychological trauma from childbirth.

For our clients, perinatal mental health has wide impacts, including but not limited to breastfeeding; parent-infant attachment; future birth choices; fertility choices; self-worth; feelings of inadequacy, shame and guilt; relationship challenges with self and others, and intimacy concerns.

Impact during the pandemic

It would be neglectful not to mention the increased stressors of the past two years with recent studies continuing to show that “global maternal and foetal outcomes have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an increase in maternal deaths, stillbirth, ruptured ectopic pregnancies and maternal depression” (Chmielewska et al, 2021). Expectant and new parents during the pandemic experienced increased family stressors, social distancing, restrictions and exposure to more distressing pandemic-related news. Lequertier et al. (2022) discovered during their research that 60–70 per cent of Australian pregnant and postnatal participants were receiving no form of mental health support while reporting clinically significant depressive symptoms, highlighting a need for greater screening. Gidget Foundation Australia, a not-for-profit perinatal mental health foundation, has recently noted that in 2021 they delivered 127 per cent more perinatal mental health consultations than in 2020 (GFA, 2022). The demand for perinatal mental health supports and perinatally informed psychologists continues to grow.

Common mental health difficulties

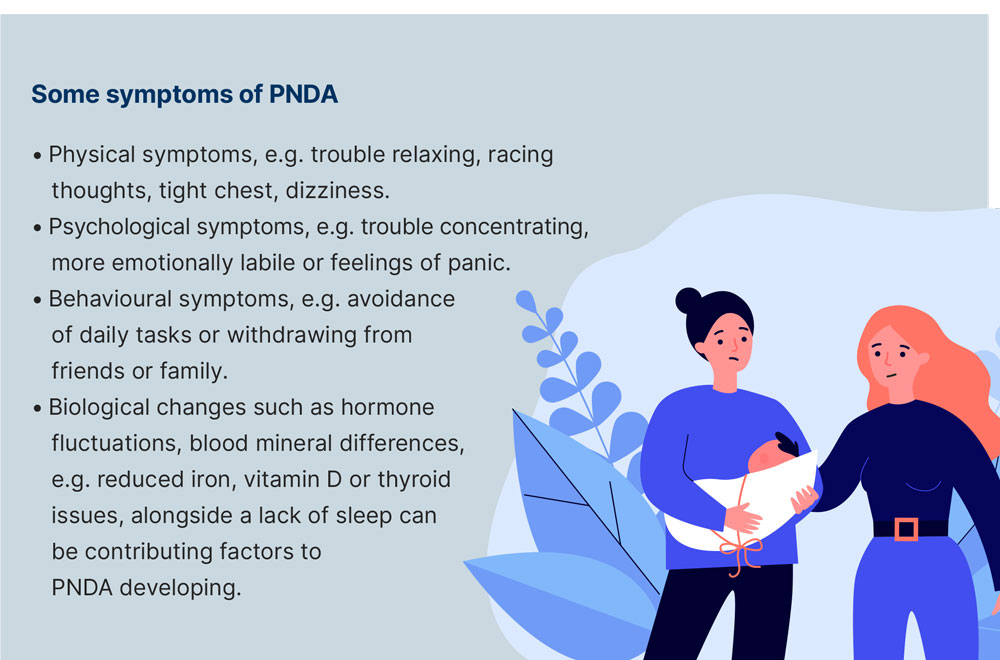

Diagnostically, presentations of new parents in this period can include a variety of mental health concerns from perinatal depression and anxiety (PNDA), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) to psychosis, perinatal loss, and sleeping and eating disorders, plus other less well-known conditions such as dysphoric milk ejection reflex (D-MER). Psychological support within this challenging period can cover themes of mental ill health, adjustment, loss and grief, trauma, fertility issues, relationship changes, body image concerns and physical health issues.

The most recognised and diagnosed condition in this period is PNDA, which affects one in five women and up to one in 10 men (GFA, 2019), with up to 100,000 Australians affected by PNDA each year.

.png)

With the updating of recent guidelines in perinatal practice and more focused training for psychologists and mental health practitioners in perinatal mental health (Gidget Foundation Australia, Centre for Perinatal Psychology, Centre of Perinatal Excellence [COPE] and the Perinatal Loss Centre), we are beginning to shine a light on an area much needing attention. Moreover, initiatives such as the Gidget Workforce Development program are beginning to bridge the gap in providing perinatal training, skill development and regular supervision to trained mental health clinicians in order to meet both client and workforce demands.

Multidisciplinary working is recommended to cover all aspects of an effective assessment and treatment plan. However, many new parents have difficulty reporting these changes as ‘different’ because they were already expecting a major change, and do not have an accurate marker to compare against.

Current psychological treatment guidelines endorse cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) as appropriate within this population, however this must be undertaken within the context of a full biopsychosocial assessment. Anecdotally, clinicians have also reported that third-wave CBT streams such as compassion focused therapy (CFT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) are beneficial in treating PNDA alongside longer term psychotherapy, attachment work, parent-infant interaction and systemic therapy.

Adjustment challenges

Up to 50 per cent of new parents experience adjustment disorders (GFA, 2020), defined by the following criteria in the DSM-5 (2013):

- The development of emotional or behavioural symptoms within three months of the onset of a specific stressor.

- The experience is clinically significant which can be evidenced through either more distress than would normally be expected in response to a stressful life event and/or having a level of distress that impacts on social or occupational functioning.

- Symptoms are not the result of another mental health disorder or normal grieving.

- Once the stressor has ended, the symptoms do not continue beyond a further six-month period.

Generally, it is not hard to meet these criteria post-birth, but many more people, while not meeting the clinical diagnostic criteria, will still experience adjustment difficulties. Emotions can often be dismissed by family and friends or even the individual themselves as being expected or normal within this period of change. Difficulties with mood can be exacerbated post-birth since during pregnancy the focus is often on psychological and physical care and attention in preparing for the birth, e.g. regular appointments with midwife/GP/obstetrician, routine scans, antenatal classes focused on health and wellbeing and dietary changes.

In contrast, post-birth there is a significant shift towards the newborn’s needs. Contact with healthcare practitioners often focuses on the baby’s development and there are very few follow-up services for the birthing partner – predominantly one routine 6–8-week health check. As such, mental health and wellbeing can often be neglected. Birth injuries and psychological difficulties are hidden or silenced as the needs of the newborn are prioritised.

Social media can play a role in compounding negative emotions as stories/ images/captions are often positively geared, evidencing unrealistic portrayals of everyday life, although Chatwin (2021) noted some positives with the use of social media being an appropriate platform to provide antenatal care and support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transitions in this phase include identity and value changes, relationship dynamic changes, and role and purpose given new meaning alongside increased responsibility to another, namely the baby.

Birth trauma

Defined as “the emergence of a baby from its mother in a way that involves events or care that cause deep distress or psychological disturbance, which may or may not involve physical injury, but resulting in psychological distress of an enduring nature” (Greenfield et al., 2016), birth trauma is thought to be the cause of 5.8 per cent of Australian women developing PTSD (Watson et al, 2021). Based on registered births in 2020 (ABS, 2021) this translates to approximately 17,000 women per year – a figure which does not account for those who have experienced perinatal loss in any form or those who experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress that did not meet the criteria for the diagnosis.

As birth trauma is a subjective experience, it is worth noting that Ayers (2016) approximated that one-third of women describe their birth as traumatic and present with post-traumatic stress symptoms. Moreover, 45.5 per cent of 866 birthing women in Australia deemed their childbirth to be traumatic on follow-up at 4–6 weeks after birth (Alcorn et al., 2010). While they may not meet the criteria for diagnosis, symptoms have a significant impact on attachment to baby, relationship to self or others and overall daily functioning. Furthermore, postnatal PTSD can present co-morbidly with depression and anxiety, leading to misdiagnosis and therefore ineffective treatment. Treatment by experienced psychologists is therefore essential to ensure appropriate diagnosis, formulation and intervention. Many therapeutic modalities are appropriate for working with birth trauma however those showing stronger evidence include trauma focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TF-CBT) and eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) (NICE, Clinical guideline [CG192], updated 02/2020). While more research is needed to explore outcomes for women utilising these treatments, there are clear ethical considerations in doing so.

Additional vulnerabilities

Women who have existing or past mental health issues are also more vulnerable in the perinatal period. Lequertier et al. (2022), in the context of COVID-19, again found that women living with “a pre-existing health issue of disability showed higher odds of elevated depression” (p11). However, this is also true more generally with pre-existing family conflict and/or socio-economic pressures, presenting increased vulnerabilities for perinatal clients.

Fathers and co-parenting partners are routinely missed through early screening programs (Darwin et al., 2021). This has implications for the mental health and wellbeing of the parents or couple, as well as their child, e.g. attachment, bonding, parenting styles and healthcare services. Partners are not yet prioritised in either policy or service intervention although this is beginning to change with many companies supporting shared parental leave (Walsh, 2019). This is also key when we consider more marginalised voices such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, minority ethnic parents and LGBTQIA+ parents. Best practice would suggest including partners in the screening and treatment is essential in establishing best care, to increase recovery rates and enhance family cohesion and outcomes.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, practices around birthing are deeply connected to community, land and country. In more regional and rural communities, due to medical risks more women are being moved away from community and country, impacting on overall wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Marriott and Ferguson-Hill (2010) comment that this “may well upset the normal process and rhythm of birth as well as subsequent mother-child interactions and child behaviour and development” (p340), therefore creating more vulnerability in developing perinatal mental health conditions. Moreover, they suggest that one way to mitigate this is to create practices which are culturally sensitive to “spirituality and the relationship with family, land and culture” (p340).

Key to working within this population is consideration to the past and ongoing impacts of transgenerational trauma, grief, loss, alienation from kinship and other factors which predispose Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to greater complexity during this period. Utilising appropriate screeners, support systems and developmental/attachment frameworks are essential alongside recognising the inherent vulnerabilities and power dynamics inherent in a western medical model of healthcare. In addition, psychologists have been recommended to provide therapeutic modalities including “narrative and demonstration, personal stories and anecdotes, open ended discussion, yarning, and grief and loss therapies” (p341).

For psychologists

Psychologists play a key role in early intervention within this perinatal population. We are uniquely positioned at a time when women are more engaged within the healthcare system and therefore well-placed to both screen and engage expectant and new parents in psychological intervention. Moreover, women are less inclined to depend on pharmaceutical interventions due to concerns about the impact of medication on pregnancy, post-birth or breastfeeding. The current research highlights that early intervention can have a protective factor with a recent review of the “Pre-admission Midwife Appointment program (PMAP)” evidencing that, “all women who attended the PMAP experienced a decrease in depression symptom severity, irrespective of whether they had been identified as being ‘at risk’ during the PMAP appointment” (Kohlhoff et al, 2022). Appropriate screening using recommended evidence-based tools such as Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale (EPDS), Kimberly Mums Mood Scale (KMMS) or Baby Coming You Ready? is a necessary aspect of early intervention. Interventions were also found to be most effective when integrated with routine healthcare settings since this may help to reduce the stigma but also allow for earlier detection and intervention. Waqas (2022) comments that early intervention has the added benefit of improving treatment-seeking attitudes and can be implemented within a variety of culturally sensitive contexts.

Treatment is underpinned by an attachment framework with a focus on both maternal mental health and infant mental health while holding the partner in mind. Psychologists work across a variety of settings including private practices, mother-baby units, Perinatal Mental Health Services (PMHS) which includes community and outpatient settings, and third sector organisations. This can involve liaising with GPs, obstetricians, child health nurses, public services and child protection services. As with much of our clinical work, the perinatal period presents unique risks which require thorough and robust assessment

and management.

Helping at every level

The scope of psychology is not limited solely to clinical work or academia in the field of perinatal mental health. In fact, adopting a systemic approach to tackling issues, psychologists have a multifaceted role at various levels including government, policy, community and individual. McNab et al (2022) comments, “Without this work, we will continue to contribute to the silent burden carried by women and their children” (p3).

Perinatal mental health considers maternal mental health, infant mental health, parenting and relationships, and it impacts on multiple systems at a great cost to society. Prevention, early intervention and treatment are essential to reduce this burden and psychologists are well placed to tackle the challenges. On a personal level, working within the perinatal mental health field is hugely rewarding since despite complexities, recovery often happens relatively quickly and the positive effect on all is readily observed.