Important contributions from psychology

I write this article from the perspective of a sport and exercise psychologist who works with injured athletes, a psychologist who works with people suffering from persistent pain and injury, and as a person who has and continues to suffer from persistent pain myself. With pain having been the focus of the APS National Psychology week in 2020, I have reflected on the work I do with clients experiencing injury and pain and the major themes that present themselves in this work.

The majority of clients I see in the pain and injury space acquire their injury from sport, a workplace or a car accident, whether that be while working or out-of-work hours. On the odd occasion, a client will be referred due to pain developed over the normal wear and tear of a life well-lived and a number of clients are referred for injuries suffered during previous military service but who are now living civilian lives.

The client has typically been consulting with a number of other professionals and it isn’t until months or sometimes years after the onset of injury that the client is referred to a psychologist. It is this kind of late-in-the-game referral that can make it difficult to develop great gains with the client in either the short or long-term. As a result, clinical goals must be reviewed to ensure realistic expectations.

Other than with sport clients, the typical client is usually under the auspices of an insurance company whether that be a worker’s compensation scheme, a Comprehensive Third Party (CTP) insurance scheme, National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) or the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). As a result, the client is generally represented by a personal injury lawyer although this is less often the case when it comes to DVA and NDIS where there is generally an intermediary between the client and insurer – generally, a case manager. I understand that many psychologists baulk at working within the insurance domain and I concur with their frustrations at difficult decisions made by insurers, the onerous expectations of reporting and difficulties of disclosure.

However, if one can accept these aspects of the injury space, there are many benefits to working with such clients including the collegiality of working with other professionals and the far greater support granted the client than is often possible in the private billing or Medicare context. From a ‘psychologist as business proprietor’ point-of-view, that we are all so reluctant to discuss, there is a steady stream of clients to work with and the financial outcomes for both client and therapist are sound. Ultimately, if one chooses to work within the injury field, insurance companies are a necessary part of the work that equally create frustration and benefits alike, for both the client and psychologist.

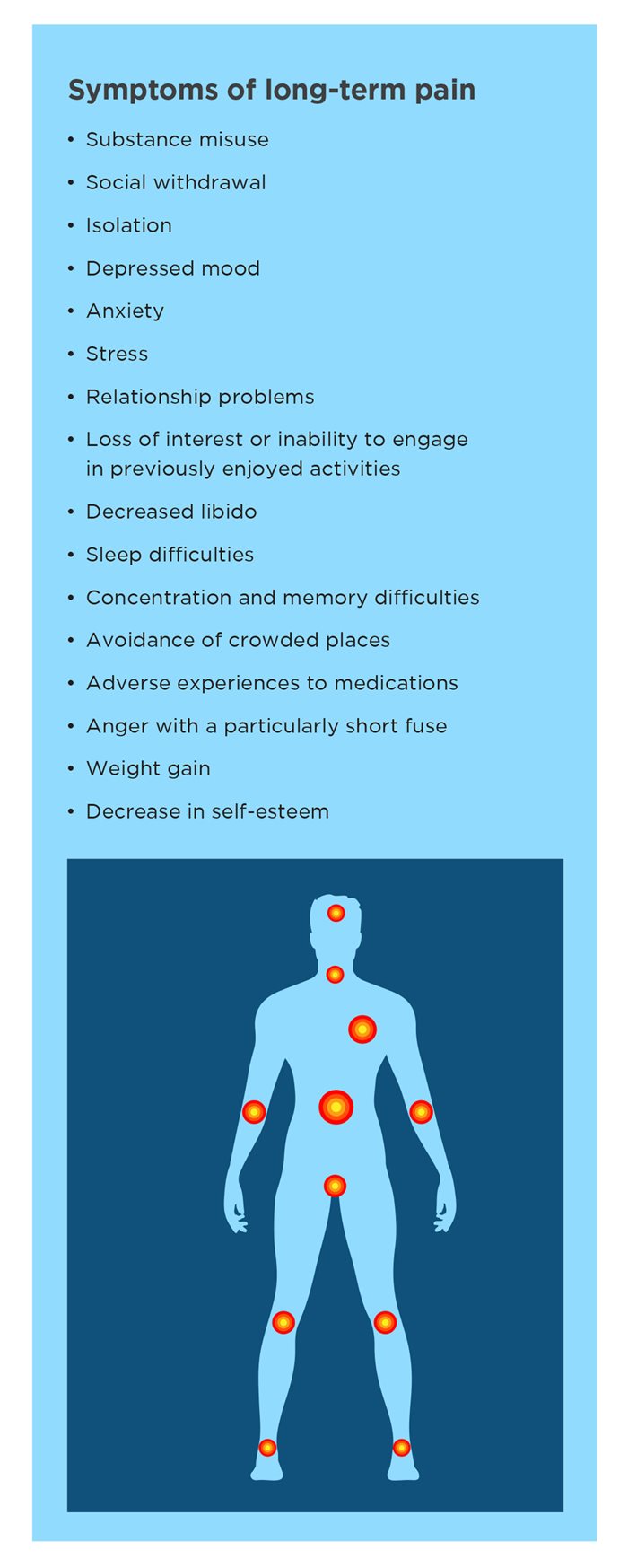

The client experiencing long-term injury or pain is likely to present with a variety of symptoms. Many of these symptoms correlate strongly with a number of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Given that injury and pain are ‘threat signals’, it is perhaps no wonder the symptoms are similar. Not every client will suffer from all symptoms, but a majority of these will be present.

Prior to the first appointment, I request that clients complete a variety of questionnaires. The results of the questionnaires are important to case formulation as well as to establishing diagnoses that are particularly important in the insurance and legal realm. Questionnaires that I find particularly important measure mood, pain, catastrophising and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; if pain is a result of a traumatic event such as a car accident).

The most common diagnosis for clients suffering from long-term injury and pain is adjustment disorder. If within the intake and scoring of the questionnaires there is an indication of depression and/ or anxiety, the diagnosis could be adjustment disorder with depressed mood, with anxiety, or with depressed mood and anxiety. Should the symptoms of trauma from the injury be of sufficient level a diagnosis of PTSD might also be appropriate. This is not to say other diagnoses are not appropriate, but these are the most common.

Finally, to describe the typical client who seeks psychological assistance, the observation is that the term ‘seeks’ is an overstatement. The majority of clients referred to me for therapy have not gone to their pain specialist or GP and asked to see a psychologist, but it has been recommended. This can be confusing for the client as they have sought assistance for a physical problem, not a psychological one. As a result, it can be highly beneficial to spend time discussing the benefits of psychology with someone experiencing pain either before or during the first appointment. The client who is sceptical of seeing a psychologist often surmises that their doctor does not believe they are in pain and that their pain is “all in their head”. It is important to reassure a client that their medical professional absolutely accepts that they are in pain but believes that they could use some support to navigate their way through their pain journey.

Now that we have the ‘typical’ presentation I will discuss some of my observations from working in pain and injury and the nuances associated with the endeavour, starting with the multidisciplinary team.

The multidisciplinary team

Clients are often referred as part of a larger multidisciplinary team including pain specialists, surgeons, general practitioners, psychiatrists, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists and other allied health professionals. Other important persons within the clients’ multidisciplinary team that are often left out of the conversation are the clients’ case manager at the insurance company, their lawyer and without question the client themselves. The multidisciplinary team I work within practice independently of each other, but very much together. If I could make only one point within this article, it is the sheer importance of the multidisciplinary team in the pursuit of positive outcomes for the client.

It is important to note that as the team focus is on positive client outcomes, clients can at times become reliant on the team with such dependence becoming detrimental to positive outcomes. This is a tricky scenario to navigate and is mostly experienced with long-term clients. In my experience, the client will likely continue to see the psychologist while other team members gradually wean the client from their services.

As indicated, the psychologist is often the last person the client is referred to in the team, however, I believe the benefits of psychology to pain and injury are best seen when intervention occurs early. Other than working with the client, the psychologist makes a number of important contributions to the team. The first is to provide advice to other members of the team on how best to work with the client, within their area of expertise. Clients tend to bring their personalities to the experience of injury and pain and advice in this regard can assist others to get more effective results with clients. Second, the psychologist can help the client in communicating back to the team or an insurance company any issues the client is having in order to resolve any interference. Empowering the client to address issues is critical. A third role is assisting surgeons in preparing clients for surgery in what is referred to as ‘prehabilitation’. This is an interesting progression of the work I do in pain and injury that is intended to assist the client to get ready for surgery where the surgeon suspects their level of anxiety or readiness for surgery could interfere with the most beneficial outcomes, particularly knee replacement surgery.

Ethical challenges

Within the multidisciplinary team, it is essential that the psychologist communicate effectively with the various team members. Disclosing client information can be a confronting aspect of working within a multidisciplinary team. It is essential that clients are informed from the outset how you as a psychologist will work across the team and to seek the client’s permission to share information where necessary. Clients generally understand the importance of a coordinated approach. Any disclosure should be specific to the clients’ experience of injury and pain and not disclose information about other aspects of the client’s life unless it is vitally important.

Treatment goals

For psychologists, there exists a common goal to end or relieve the suffering of their clients – but not necessarily the end of the client’s pain. It is my experience that the initial physical ailment for which the client is seeking assistance (i.e., injury and pain) is not something a psychologist can remedy as treatment is in the hands of doctors and physiotherapists. What psychologists can assist with is the psychological difficulties experienced as a result of the pain. As an example, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) “is a chronic nerve pain condition that usually affects the arms, legs, hands or feet. CRPS can occur after injury or trauma and is believed to be caused by damage to, or malfunction of, the nervous system”, however CRPS can also develop without any obvious pre-existing injury” (Pain Australia, n.d).

CRPS is a horrible disorder with no cure and is rated as the highest level of pain a person can experience, above that of amputation or childbirth (Melzack, 1975). So terrible is the condition that it is anecdotally referred to as the ‘suicide disease’. In such cases, I reflect that an effective goal for therapy is to cease the continued slide down the rabbit hole towards psychological oblivion and maintain what might be referred to as adverse mental health rather than to pursue an expectation of positive mental health given the circumstances.

While a client continues to experience pain and injury, it is unlikely that they are going to be happy about it or return to the relatively positive mental health state they were in prior to injury. Something I have to continually reinforce with insurance companies is that the nature of adjustment disorder means it will be maintained until approximately six-months post the removal of the stressor. Therefore, to imagine a client will return to pre-injury levels of mental health whilst they continue to suffer from injury or pain is for the most part a futile exercise.

Instead it is preferable to adopt a position of ‘attendant’ as was the original derivation of the word therapist from the Greek, therapeia – ‘to attend to’ (Spinelli, 2005). Within the mode of attendant, I develop a stance of ‘journeying’ with the client. Any and all education, pain strategies, tricks, and techniques are implemented with the client in the early sessions and therefore ongoing therapy is devoted to assisting the client with maintaining effective strategies and helping them to work through issues as they arise throughout their rehabilitation and recovery. Working with clients in the pain and injury space long-term can fill up an appointment schedule quickly.

Having provided a fairly doom and gloom perspective of the client experience of injury and chronic pain conditions, I do challenge clients with an aspirational goal. Given that a client might be afflicted with a pain condition that is enduring, I challenge them with the question, “How can we work towards you getting on with your life despite your pain?” I am sad to report that often times, clients are unable to take up the challenge. The suffering that clients experience with injury and pain can prove too much to bear.

Effective psychological strategies for treating pain

There are some strategies that I strongly advocate for clients. When used effectively and consistently, they can help in managing pain and other issues clients face as a result of injury and pain.

- Psychoeducation about pain and how psychology can help.

- Encouraging a client towards treatment adherence (e.g., completing at home exercises).

- Distraction – taking up a hobby, going out with friends, reading.

- Mindfulness and meditation – particularly guided meditation (a range of apps for both are available).

- Acceptance – accepting that this is happening rather than denial or avoidance.

- Identity – reminding the client they are more than the identity they might need to give up on due to pain or injury, i.e., the athlete is not just an athlete and the carpenter is not just a carpenter.

- Finding meaning – What can be learnt, developed or improved upon during this period? For example, is there a relationship the client has been neglecting that they now have time to work on?

Diaphragmatic breathing – I have found this to be the most effective tool for reducing both anxiety and pain. I generally work with clients to use diaphragmatic breathing in five different ways:

1. To regulate anxiety, frustration or anger at the time it is triggered.

2. At regular intervals throughout the day to maintain a more relaxed posture both physically and mentally.

3. Prior to and in preparation for a situation that they recognise is likely to cause them anxiety, e.g., a job interview or medical procedure.

4. Breathing into their pain – Pain is often discussed as a ‘tightness’ so I encourage the client to imagine that with each breath the area where they experience pain is expanding. With the outbreath they are imagining ‘blowing the pain away’ and relaxing the body, particularly in the location they are experiencing pain.

5. Breathing out on effort – Many people who experience pain hold their breath or brace when they expect a movement to hurt. Bracing only works to reinforce the pain. Just like working out in the gym and breathing out on the contraction of a muscle, I encourage clients to do the same whenever they are engaging in ‘effort’ around the house. For example, when getting in or out of a chair, getting in and out of the car, bending down to pick something up off of the floor.

A call to arms

Working in the injury and pain space can be a difficult proposition as a psychologist. However, it can also be rewarding in many ways. One thing is absolutely guaranteed once a psychologist establishes themselves as someone who works with pain and injury clients, there will never be a shortage of health professionals referring clients to you nor clients in need of assistance. There is without question a need for more psychologists to work with clients experiencing chronic pain and injury and I do hope that I have gone some way towards providing an authentic insight into the work that psychologists face when taking on a client with an injury and pain.

Contact the author