Healing clients and the public mental health system

As the only access point to tertiary mental health services that guarantees you will see a clinician the same day, emergency department presentations have been rising over the past 10 years. This trend appears to be consistent with what is happening in Australia more broadly, and certainly Australians are accessing mental health services more than ever (AIWH, 2019a; Whiteford et al., 2014), but does increased access mean better mental health?

Prescriptions for antidepressant medications in Australia doubled between 2000 and 2015. As a nation, we are now the second highest prescriber in our band of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries at 104.2 daily doses per 1000 people per day, behind only Iceland (OECD, 2017). The national suicide rate is also rising. In 2017, 3128 Australians died from intentional self-harm; an increase of 9.1% from 2866 in 2016 (ABS, 2018a).

Despite service increases, epidemiological and national surveys show no improvement in adult mental health (Jorm & Reavely, 2012). The rate of Australians experiencing a mental or behavioural condition is on the rise, largely due to a higher rate of anxiety- and depression-related conditions (ABS, 2018b). Our country is experiencing rising treatment rates and more risk but less mental health.

Increased suffering has been accompanied by higher costs. In 2017–2018, 10.2 per cent of the Australian population received Medicare-subsidised mental health services, almost doubling from 5.7 per cent in 2008–2009 (AIHW, 2019b).

Five years ago at Monash Health, we analysed why the mental health system was not delivering value to clients. That work led us to develop a series of systems interventions that have since yielded significantly improved client outcomes. Our journey to a new model of care for mental health is the focus of this paper.

Crisis and biomedical management

At Monash Health Victoria we set out to understand why presentations to our three emergency departments had increased tenfold over a decade by applying systems behavioural analytics. This told us that the percentage of new clients was inversely related to increasing re-presentations. That is, more of our clients were returning over time. Given that half our emergency presentations are admitted, the pressure on our inpatient beds was not a surprise.

Further, we investigated the clinical value of our mental health community teams. Analysis showed a similar pattern of re-presentations, particularly for those clients accessing crisis and assessment team services. This research was accompanied by activity analytics to understand the client experience (an example is shown in the infographic above).

We used data from the Service Unit Value tool (SUV; a tool that provides a relative value based on patient outcomes and service cost over time) to generate insights as to why people re-presented after receiving an episode of specialist treatment. We asked ourselves if the re-presentation was due to the nature of their severe and enduring mental health condition, or a result of failure demand in that we had not delivered the care that the client needed to continue their recovery. Critically, the SUV tool provided us patient data over time and this enabled us to dig deeper and see that clinical services we were providing were not meeting our clients' needs. It enabled us to conclude that we needed dedicated trauma treatment.

We all know that people present to health services with issues that are secondary to their mental health condition, the SUV analysis enabled us to see that we had been treating many clients who were representing on mental health issues that were secondary to their trauma.

This work gave us eight key insights as to how we could improve care for mental health clients:

- The system emphasises biomedical and risk management, not biopsychosocial treatment.

- There were many handoffs and transactional activities but too little evidenced-based care.

- The medicalisation of mental health for high prevalence disorders and the unintended consequences such as reducing the emphasis on self-help behaviours, personal efficacy and agency.

- Some clients were being discharged in a worse state than when they were admitted.

- Clinicians experienced episodes; clients experienced the system of care.

- Visualising the client journey changed our perspective from clinician to client.

- Our existing measurement tools and performance indicators for quality improvement were not delivering clinical value to clients.

- We learned most of how we could improve clinical care from our re-presenting clients.

Continuous learning through co-design

It is widely acknowledged that healthcare is the most complex of adaptive systems. As a result of this complexity and the way programs are funded, many agencies offer discrete services that result in little coordination for the patient between workers, within and across programs, sectors and the system.

The mental healthcare system should not be considered in the context of its component parts (like clinics, inpatient services, community clinical services, and related services like housing, social and occupational support services), as this is not how clients and their families are best served. Rather, service delivery should be organised in terms of its interrelations, which ensure client needs are met through a series of connected and value-adding services.

Since 2014, Specialist Psychological Services at Monash Health has continuously analysed, hypothesised, prototyped, listened to, measured, learned and iterated what clinical services our clients need to stay well. By understanding why our clients re-presented, we generated significant insights that were not immediately apparent when we embarked on this program of work.

A value proposition has been developed to implement a co-design treatment program with clients in situ, so that all clients:

- have an opportunity to co-design the treatment they experience whilst in treatment (as measured through a Patient Reported Experience Measure, (PREM))

- leave treatment better then when they presented on issues that matter to them (as measured by patient reported outcome measures (PROMS)).

If clients do re-present, it means that what we provided was not sufficient to meet their clinical needs and we prototype new clinical services and measure for purpose, outcomes and experience. We have termed this broadly as our agile clinical services. This is translational clinical science in action.

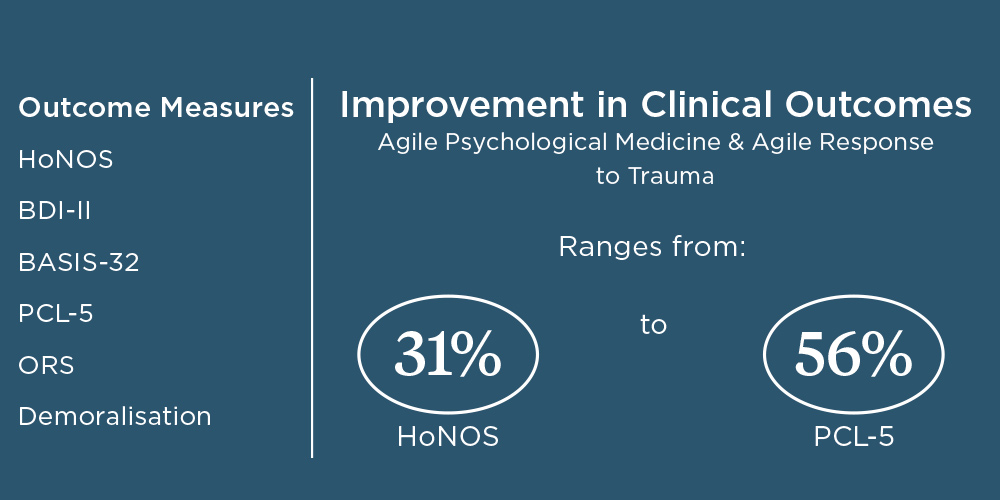

The PROMS and PREMS have demonstrated that when clients receive early access to feedback informed treatment in Agile Psychological Medicine (aPM) it leads to improved clinical outcomes and experiences.

As a result of studying why some clients were re-presenting, we have expanded our clinical services to provide specialist evidence-based treatment for mood disorders, trauma and PTSD, as well as for our top 20 frequent presenters to emergency services (some of whom present over 100 times a year). Improvements in service utilisation are presented in Figure 1.

Towards agile psychological medicine

Over the past five years, the process of innovation by Monash Health’s Specialist Psychological Services Program has delivered ongoing value-based mental health care, as defined by improved client outcomes and experience, and measurable by client feedback. To understand how the system is behaving, systems behavioural and patient activity analytics are also used. The service unit value is a tool designed to enhance continuous learning and deliver value in clinical services in keeping with community needs.

It was in the process of prototyping service innovations delivering evidenced-based psychological care that we gained valuable learnings about the forces that had maintained the status quo since de-institutionalisation in the 1990s. “It is difficult to understand a system until you try and change it and when you do try to change it, only then will underlying mechanisms maintaining the status quo emerge.” (Shein, 2005).

From observing the number of forces that emerged when we started to change the mental health system of care through the agile prototypes, an organisational formulation was developed naming the forces maintaining the status quo. The formulation was key to informing the multi-tiered interventions required to sustain the ‘agile innovations’ at a people, process and systems level. Interestingly, data evidencing value to the client was not sufficient. The formulation also begins to identify why the mental health system has been so difficult to change over the past 20 years.

Leaders are key

Our research identified that middle-management is the key intervention point when fostering innovation and quality improvement but they need more authority and professional competencies if they are to lead change in a complex system that supports the status quo.

To create an environment that facilitates agile design in the delivery of mental health services, executives need to provide more psychologically enriched environments for middle managers and staff that facilitate greater problem-solving and team cohesion through shared purpose.

As psychology professionals there is obviously an element of resilience required to open-up what we do to feedback from clients, but the Monash Health experience is that such environments enable staff to become the best versions of themselves and, by extension, deliver high-quality evidenced-based clinical interventions for clients.

In our experience, the aPM model of care is a win-win. New energies are unleashed in the workforce to deliver change while the ability to listen and join relationally with the client creates a partnership approach that accelerates the client’s journey to recovery.

Acknowledgement

The success of our Agile Clinical Services results from the relational work led by our dedicated psychologists and clinicians co-designing treatment and services with their clients. Our design and innovation work is supported by Dr Dinali Perera, Ms Moana Waerea, Ms Ashlee Gravell, Ms Ashley Zheng and Ms Marcella Tulchinsky.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]