In the research community there is an increasing desire to see scientific research become more accessible and transparent. Yet we retain many systems (e.g., academic publishing and the protectionist approach to experimental processes) that provide roadblocks to disseminating our research more broadly. Open science provides a way forward and has an ever-increasing number of followers.

What is open science?

Whenever I need a definition for something, I usually turn to the definitive source: Wikipedia. It defines open science as transparent and accessible knowledge that is shared and developed through collaborative networks. In more detail, open science is comprised of the following elements:

- Open access – offering free access to the papers that describe the outcomes of research, thus providing unfettered dissemination of science. Current practice means that the researcher has to pay a substantial fee for open access and for the pleasure of having other people read, cite and possibly even critique their research.

- Open data – sharing data so that it is open to others to allow for important practices such as metaanalyses, but also to allow other researchers to see if they can reproduce your findings.

- Open practices – providing detail about the procedures and techniques and statistical analyses involved in the research, thus allowing for the greatest transparency in research communication. One aid to this (“keeping the bastards honest”) is the specification of protocols before analyses of the data commence. This ensures that new hypotheses do not emerge, that the main outcome variables are not cherrypicked in order to tell the most favourable story, or that analyses maximise reporting of significant results. Some countries now require registration of ongoing trials, such as the United States (clinicaltrials.gov), which requires inclusion of the study description, hypotheses, study design, arms and interventions, outcome measures (primary and secondary), and eligibility criteria. Some authors additionally publish study protocols, which permits peer review of the detail of the trial, including the statistical analysis.

- Open collaboration – supporting researchers to take part in prepublication sharing. Many universities have developed a storage system for accepted but pre-published work in order to meet the requirements of granting bodies and websites now exist to facilitate this process, including the Open Science Framework (OSF). Good science needs to get out quickly, benefiting society as a whole.

Re-emphasis of open science

Truly nothing is new under the sun. Open science was born in the 1600s with the emergence of scientific societies and journals. The Royal Society had the motto “Nullius in verba”, which can be broadly interpreted as “take nobody’s word for it”. Back in the days when science was taking off, researchers had the luxury to hear about and question, and sometimes fiercely debate the veracity of most of the research that was occurring. The expectation was that results would be replicable over repeated trials, and that experimenter prejudice or opinion would not be permitted to impact on the results. One of the most famous examples of this occurred in the 1860 Oxford evolution debate, seven months after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Darwin was too anxious to attend – and was rumoured to have a hypochondriacal attachment to the toilet closet that he had specially built in his study. So Thomas Huxley was called upon to represent Darwin’s work instead. The debate was reported as follows in the Oxford Chronicle:

Mr Darwin, whose treatise on the development of the species has been the book of the season, did not appear at the British Association. His place was well-filled by Mr Huxley, who on Saturday had to do battle for the new doctrine. “If I may be allowed to enquire,” said the Bishop of Oxford, “would you rather have had an ape for your grandfather or grandmother?” “I would rather have had apes on both sides for my ancestors,” replied the naturalist, “than human beings so warped by prejudice that they were afraid to behold the truth.”

Jumping forward a couple of hundred years, we can no longer scrutinise all the science that is emerging, and the pressure is on to publish – not necessarily quality research – and to publish a lot. In this environment, mistakes can happen, slightly less than optimal procedures may be adopted to save time and in rare circumstances, outright fabrication of interesting (i.e., publishable) results can occur.

Enter what has been termed “a year of horrors” by Eric-Jan Wagenmakers. In 2011, the much-revered Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (JPSP) published a paper by Daryl Bem that found that people could look into the future, an ability enhanced if you happened to be an extrovert woman looking at erotic pictures (I think you need to read the original to understand why anyone would look at this). JPSP then covered themselves in infamy by refusing to review any paper that failed to replicate these results. This was also the year that Diederik Stapel, a rising social psychologist from Tilberg University, admitted to fabricating much of his data. Again, in a classic example of the publication bias effect, no studies had been published which failed to replicate Stapel’s effects. Psychology is by no means the only discipline that experiences these problems, but Stapel made it to number one in the top 10 cases of scientific infamy in 2012.

Most of us can rest safe in the knowledge that we would not commit such breathtaking fraud. Before we relax too much, enter the Open Science Collaboration, which in 2015 published an earth-shattering paper in Science (doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716). Brian Nosek – a social psychologist and head of the Center for Open Science in Charlottesville, Virginia – and 269 co-authors repeated work reported in 98 original papers from three psychology journals to see if they could independently produce the same results. Only 39 of the 100 replication attempts were successful. The news gets worse. This is likely to be an optimistic estimate, as the Reproducibility Project targeted work in highly respected journals, the original scientists worked closely with the replicators and replicating teams generally opted for papers employing relatively easy methods. This problem is not limited to social psychology. Indeed, Tackett and colleagues (2017) provide a thoughtful discussion on the implications of safeguarding replicability in clinical psychology.

Torture the data and it will confess… even if it is innocent

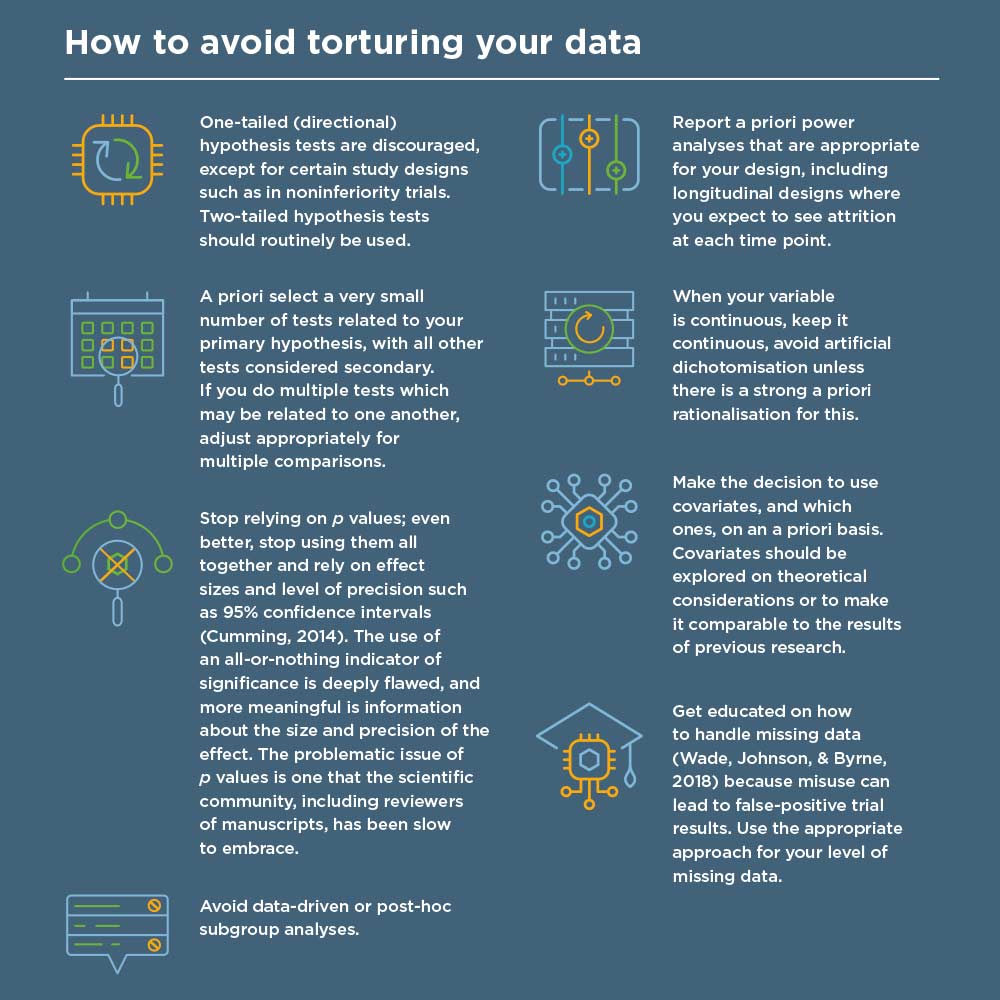

We’ve all done it, haven’t we? Pushed the data around until we have analysed every possible variable. Manipulated it every which way as we look for different statistical analyses that will give us a publishable story. Data dredging or ‘p-hacking’ is the misuse of data analysis to find patterns that can be presented as statistically significant when in fact there is no real effect. There are numerous ways we can torture the data, including using creative outlier-rejection, selective reporting, post-hoc theorising, analysis of sub-groups and not adjusting for multiple comparisons. The infographic offers reminders about how to avoid torturing our data, which can be found in greater detail in the International Journal of Eating Disorders: Statistical Guidelines.

Being an open scientist

My lifelong heroine is Marie Curie – one of the few people in the world to be awarded two Nobel prizes. When I was 10 I asked for and received a microscope for my birthday. Fortunately, we no longer need to peer down a microscope in a draughty shed with radiation leaking into our bodies and developing cancers for the cause of science. We can, however, still follow Curie’s example and focus not on fame or ownership of our research, but on real and robust discoveries that can be circulated to the public so it can (hopefully) make a difference.

Open science is a way of assisting us to stay honourable and transparent as scientists. We are all challenged by a rapidly changing environment and the need to constantly update our practice. The following are some ideas of what we need to be doing if we are to be open scientists.

Open data

Make your data publicly available and provide enough description of the data to allow independent researchers to reproduce the results of published research studies. An example of a qualifying public, open-access database for data sharing is the Open Science Framework repository. Numerous other data-sharing repositories are available through various Dataverse networks and hundreds of other databases available through the Registry of Research Data Repositories. There will always be circumstances in which it is not possible or advisable to share data publicly, such as when sharing could violate confidentiality, is inconsistent with intellectual property agreements, or may be part of an ongoing study from which the authors intend to publish more papers. In these cases, scientists should be prepared to justify the reasons for non-availability.

Open sharing

Share the research instruments, questionnaires and materials that you have developed in a publicly accessible format, providing enough information for researchers to reproduce procedures and analyses of published research studies.

Preregistration

There are many repositories such as Open Science Framework, Clinical Trials, or Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry that will accept preregistration of research plans (research design and data analysis plan) prior to engaging in research. There is, of course, the expectation that you will follow the preregistered design and data-analysis plan in reporting your research findings.

Open access

Most journals now do offer an open-access option, which means paying a not insubstantial amount of money to have your published paper available on this platform. Budget for this expense in grant applications, talk to your universities about making such funding available, and use university storage systems to make your work available to all.

Moving forward

In 2014 Brian Nosek described three basic principles from psychological science that explain why we struggle to preserve our own research products. First, knowing what one should do is not enough to ensure that it gets done. Second, behaviour is often dominated by immediate needs and not by possible future needs (e.g., “I know what var0001 and var0002 mean, so why waste time writing the meanings down?”). And third, the necessary changes require extra work; we are too busy for things that make our lives harder.

The third reason in particular resonates with me and explains somewhat why I am not the poster child for open science. All of us are trying to be the best scientists we can be, but that is often not enough. We also need to strive to be transparent about our practices and our products; and that demands another level of effort, thought and commitment.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]