The case for including psychology in the NSW science curriculum

In 2008, the momentum of an Australian Curriculum (AC), which specifies what all young Australian’s are taught, gained traction in both the publics’ and Governments’ best interests (ACARA, 2016). Nearly a decade has now passed since the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) was commissioned and as of 2019, all states and territories have begun to implement, or have implemented, the AC. NSW led the charge in 2013 with English, mathematics, and science and technology. In a similar trend, psychology as a senior secondary course, which is not included in the AC, has been recognised and delivered across the nation with an enrolment of more than 20,000 students each year. The notable exception to this, however, is Australia’s largest educational system. While NSW enjoys a broad, flexible and multicultural curriculum within its primary and secondary education systems, the NSW Curriculum remains the only Australian education system that does not provide a psychological science course for its students.

Why teach psychology to secondary students?

Psychology is commonly referred to as a ‘hub’ science1 and contains many sub-fields including biopsychology, cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, social and cultural psychology, personality and individual differences, learning, motivation and emotion. With the arsenal of skills that students are able to develop such as communication, literacy, numeracy and research methods, a multitude of career opportunities become available.

Links to major reports and policy

The aims of the 2018–19 NSW Curriculum Review are to:

- provide an engaging and challenging education that promotes high standards and rewards effort for all students, and

- prepare students with knowledge, capabilities and values to be lifelong learners, and to be flourishing and contributing citizens in an unpredictable, technologically focused world.

With these aims in mind, the implementation of psychology will need to include an adaptive and reflective syllabus. In 2007, as a key voice of the AC Final Report, the Curriculum Standing Committee of National Education Professional Associations stated all students should have a solid understanding of scientific content, including psychology, as well as an appreciation of how personal and interpersonal skills can be applied within human society (Curriculum Standing Committee of National Education Professional Associations, 2007).

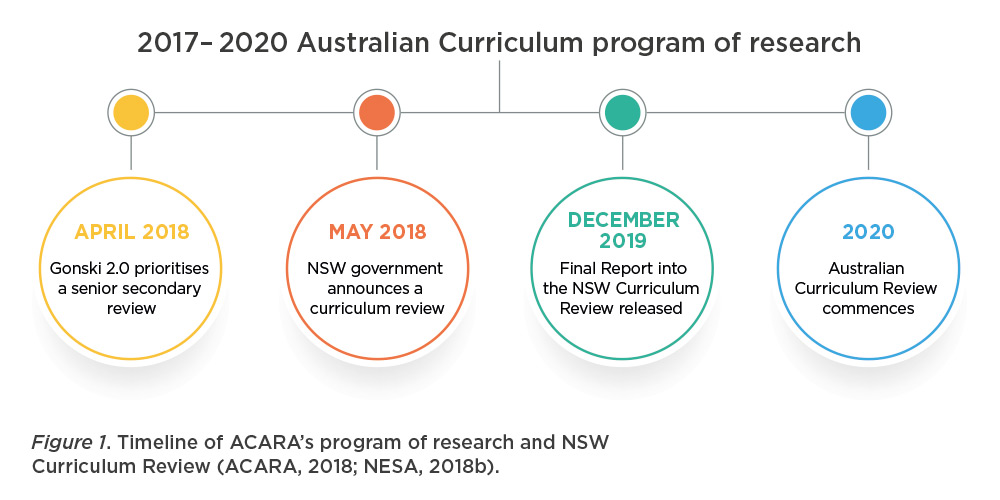

The addition of psychology will ensure that an emerging and relevant course, with cognitive science, neuroscience and neurophysiology at its core, has a key place in a future-focused curriculum (Donnelly & Wiltshire, 2014). Increasing evidence illustrates the clear links between improved academic, social and behavioural outcomes of students, and their learning experiences with interpersonal skill, supported by psychology-driven research (Review of the Australian Curriculum, 2014). Figure 1 illustrates the national educational timeline and the NSW review outline which suggests, coincidence or otherwise, that the next two years will shape the next decade within NSW education, and possibly Australia.

The highly regarded publication Through Growth to Achievement: Report of the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools, aka Gonski 2.0, has suggested that the education of our students must prepare them for a ‘complex and rapidly changing world’ (Gonski et al., 2018). Research around the implications of continued technological advancements and society are showing that routine manual and administrative activities are becoming increasingly automated. More jobs will require a higher level of skill, and school leavers will need skills that are not easily replicated by machines, such as creative thinking, problem-solving, interactive and social skills, and critical thinking (David & Brendan, 2013).

Progressing towards other educational systems

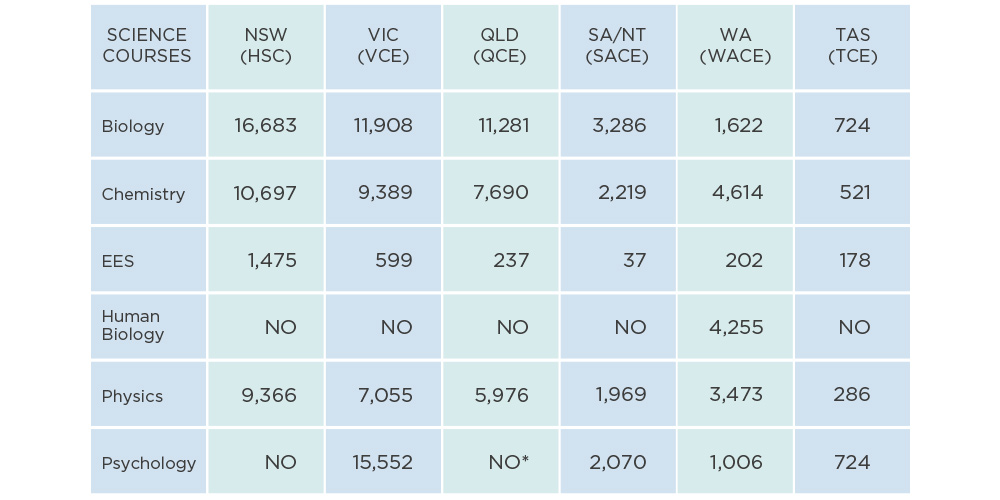

The Higher School Certificate (HSC) offered in NSW has a strong international reputation (Bagnall, 2005). However, with the increasing presence of quality interstate and international systems such as the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) and the International Baccalaureate (IB), and their rigorous psychology courses, the HSC, and by extension, a major part of the Australian education system is at risk of being left behind. For now, let’s just look at the sciences within Australia. Data obtained from each of the states curriculum authorities quickly shows a similar pattern of distribution with student course completions as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Average number of students by course and by state from 2008-2017

NO = not offered from 2008 to 2018

*As of 2019 QLD will offer psychology as a senior course subject

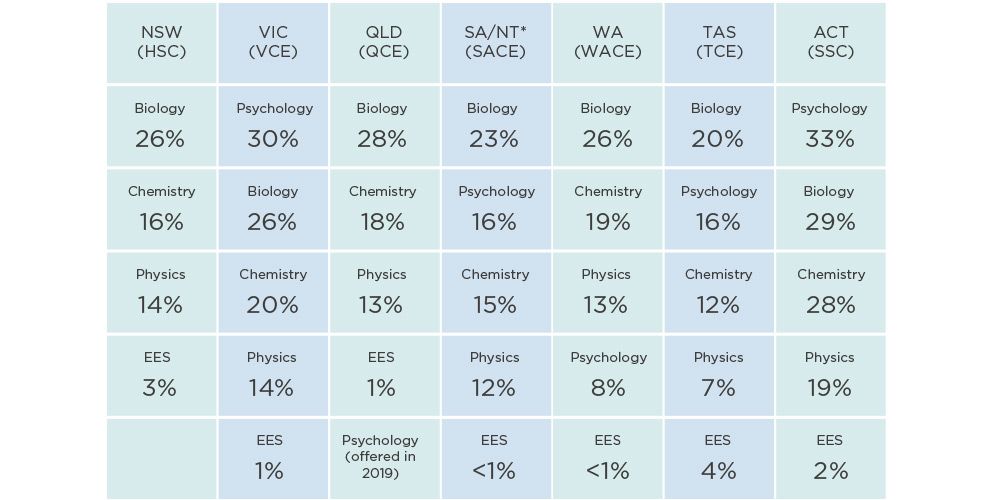

Excluding psychology, the typical hierarchy of the sciences goes from biology, to chemistry, to physics, to earth and environmental sciences (EES). However, once psychology is brought into the mix, there is an enormous change in this pattern and an increase in students completing sciences (Table 2). An interesting finding is the consistent position of the EES, even though it is one of the four senior science courses implemented as part of the AC. Findings also showed the amount of growth each course has experienced over the past decade. Biology enrolments continue to increase across all states, whereas chemistry and physics are in decline except in Victoria. EES is growing in both NSW and Victoria but is shrinking elsewhere.

Psychology has been offered from the beginning of the VCE in 1991 and has shown that it consistently enrols between 15,000 and 18,000 students each year. As part of the Western Australian Certificate of Education (WACE), psychology was only introduced in 2009 and has shown rapid growth (increasing at 33 per cent each year), while not reducing enrolments from the other sciences but adding to the total number of students engaged in a science at a senior secondary level.

Table 2. Percentage of students who completed the indicated science course2

*The SA credential, the SACE, includes NT

EES = Earth and Environment Sciences

2 Data sourced from. ACT BSSS, 2018; NESA, 2018; QCAA, 2018; SACE, 2018; School Curriculum and Standards Authority, 2018; TASC, 2018; VCAA, 2018.

Using this data, psychology would be taken up by a large proportion of NSW students which could likely result in enrolments overtaking biology (currently approaching 20,000 in 2018) and plateau for an extended time period, as has occurred in Victoria. The successful implementation will no doubt be of great benefit to our students and curriculum, and progress us to a similar state as other educational systems; but could we do more? Perhaps we should also be looking at a combination of human biology and psychology as one course, and EES/ecology as another?

Psychological pioneers

Part of the OECD’s Future of Education and Skills 2030 policy highlights the necessity for tomorrow’s schools to help our students to think for themselves and join others, with empathy, in work and citizenship. The policy goes on to suggest the role curriculum will play in assisting students to develop a strong sense of right and wrong, and sensitivity to the claims that others make. That is to say the curriculum has a responsibility to immerse their students in the world beyond the school fence and develop their personal skills particularly in boosting self-esteem and personal confidence. An innovative curriculum design that embeds future skills, improves student outcomes and is evidence-based will ensure that the increasingly high need for quality psychological information to be taught amongst adolescents is addressed (Harding et al., 2019; Maune, 2014; Torringa, Rigter, Diekstra, & Diekstra, 2014).

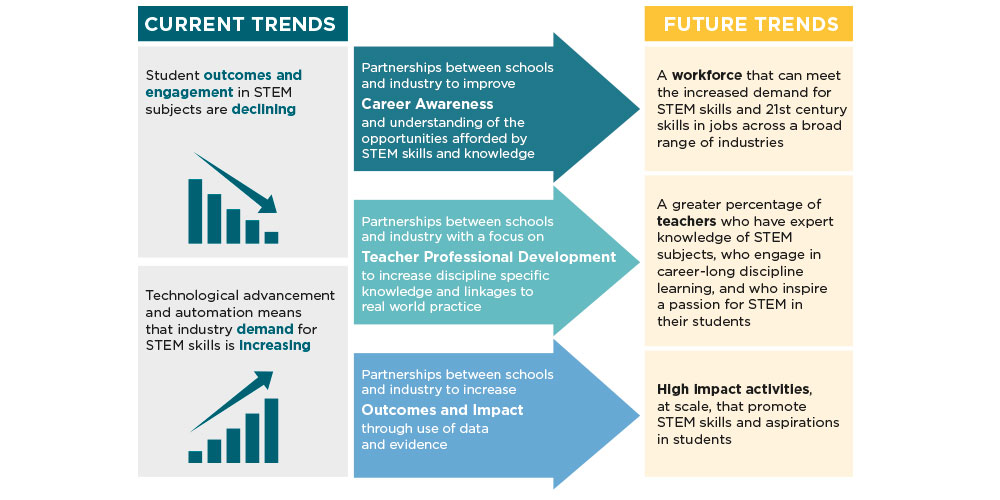

Figure 2. Addressing student outcomes and future skill demand (Education Council, 2018)

The Gonski 2.0 paper has laid down the priorities for the future of Australian education and states that every student should emerge from schooling as a creative, connected and engaged learner with a growth mindset that can help to improve their educational achievement over time. When combined with the goals of the National STEM School Education Strategy 2016-2026, to increase the number of STEM literate students and to engage in meaningful partnerships to build the essential skills required after schooling (Figure 2), psychology seems to fit in like a missing jigsaw piece.

Most schools already have these partnerships, such as with counsellors and psychologists, in place. However, they are not used for educational outcomes or teaching and learning purposes, but as student support services. Psychologists are an integral part of education systems and should take a greater role in classrooms reflecting a real-world and authentic learning experience that provides students with the right mix of knowledge, skills and understanding for a world experiencing significant economic, social and technological change.

In the USA, the American Psychological Association provides leadership, resources and professional development to teachers, schools and students. Advanced Placement Psychology, a high school course, is recognised as an advanced scientific course that employers and tertiary education systems recognise with advanced standing in their undergraduate studies. The Australian Psychological Society in Australia has already begun supporting psychology in schools, however to increase the partnerships and maximise the outcomes of students, other relevant organisations (Australian Psychology Accreditation Council, Psychology Board of Australia, etc.) will need to take up the challenge. These connections and partnerships will ensure a dedicated psychology course is implemented within the NSW curriculum and will provide the best possible outcomes for students, as well as giving them another relevant pathway for their lifelong learning journey.

To paraphrase the Science Extension Syllabus, science is not conducted in isolation. Psychology will extend and provide authentic, holistic and relevant learning experience for NSW students, and ensure they are prepared for a future in STEM learning and enterprises.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]