A schema-focused approach to the military-to-civilian transition

As a clinical psychologist, I have spent the past 10 years exploring how service life impacts soldiers and what this means for their military-to-civilian transition (MCT). Transition from the Australian Defence Force is a significant challenge for military personnel, with almost half experiencing a mental health disorder as they transition from service to civilian life (Van Hoof et al., 2018). Much of my practice focuses on adapting my usual cognitive behavioural approach to therapy to this issue. I found schema therapy (ST) to be an effective model for understanding military identity issues and assisting ex-service personnel. In this article, I outline how schema therapy can assist clinicians and clients to understand the psychological effects of service and consider related implications for the MCT process.

My journey with psychology and the military spans two decades and began when I enlisted in the Army Reserve as a truck driver while studying psychology at the University of Newcastle. After a period of service as an army psychologist, I discharged from the military about six years ago. One of the highlights of my career was working as an on-base psychologist with Special Forces soldiers in Sydney. During that time, I identified consistent and persistent patterns during client sessions, such as how the soldier felt and/or reacted in a traumatic moment was more of an issue than the traumatic moment itself, concerns they raised about their performance and competence, feelings of guilt regarding actions taken or not taken, not feeling ‘good enough’ and chronic feelings of being let down and under-recognised for achievements. Most spoke of an inability to self-identify outside of being a soldier, and it was evident to me that a soldier’s difficulties extended far beyond deployment-related experiences. A diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is often applied to military personnel, but it provides a limited understanding of the difficulties faced by many of the clients I saw, and did not substantially help treatment planning and long-term outcomes.

Given the prevalence of transition issues in the defence force community, it is gratifying to see increasing attention on military personnel and their psychological needs as they transition to civilian life. For example, it is currently being investigated by the Joint Transition Authority (bit.ly/3DqTNo2), among other organisations. From my perspective and experience, evidence-based programs to transition service men and women back into the community are crucial to maintaining and supporting long-term wellbeing.

Understanding transition

Psychological concerns relating to MCT are not new, with difficulties documented as far back as World War I (Pedlar et al., 2019). Despite many attempts to comprehensively describe and understand MCT, and develop related policies and programs, there is still no widely accepted theory or framework (Pedlar et al., 2019). There is also limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of any of the programs or the services established to support veterans at transition (Pedlar et al., 2019).

In their review, Pedlar et al. (2019) suggest the ‘life course framework’ and ‘social identity theory’ are most helpful to understanding both MCT and wellbeing considerations for military personnel. The life course framework can be applied to appraise how events, experiences and decisions earlier in life contribute to predicting and mitigating outcomes for veterans after military service (Pedlar et al., 2019). Social identity theory can be used to understand how the military identity is created through the socialisation process and the impact of losing this identity at transition (Pedlar et al., 2019). They also suggest that ‘identity resolution’ is a key consideration for MCT, because individuals with a strong military identity tend to have poorer post-military functioning. However, I think both the life course framework and social identity theory are limited in assisting understanding of how the individual makes sense of the transition into the military and then later, the move back into civilian life.

Cognitive psychology provides a theoretical framework that explains how people process information and make sense of things. Cognitive psychology differentiates between different levels of cognition (or thinking), explaining how we chunk, categorise and embed information, and develop strongly held beliefs and ideas. In the early 1920s, Jean Piaget introduced the term ‘schema’ to the field, to explain categories of information stored in long-term memory, consisting of memories, concepts or words, which act as a cognitive shortcut that makes storing new information, and the retrieval of it, quicker and more efficient.

According to clinical psychologist Jeff Young, a schema is a type of blueprint that helps people interpret information, problem-solve, and create a stable view of oneself and the world (Young et al., 2003). Schema theory, therefore, may provide both a theoretical and conceptual framework for understanding how Defence Force personnel develop and store beliefs about themselves and the military. Accordingly, a schema-focused approach may assist military personnel to understand their identity development and transition processes.

A schema helps people interpret information, problem-solve, and create a stable view of oneself and the world

Schema therapy in context

Schema therapy (ST) considers the life course of a person by exploring unmet core childhood emotional needs and the potential consequences of this in their life. ST is built on a model of five core emotional needs:

- secure attachment and connection

- autonomy, competence and sense of self

- freedom to express valid needs and emotions

- realistic limits, and

- spontaneity, fun and play.

When our core needs are met, we develop a stable ‘healthy adult’ self who:

- is self-directed (sets and pursues own life course)

- self-regulates (regulates emotions, impulses, thoughts

and behaviours)

- is connected (forms meaningful mutual relationships), and

- transcends (pursues higher purposes or meanings in life and human relations) (Bernstein, D., 2021).

When a core need is unmet, a person can develop a maladaptive mental representation or schema about themselves, others or the world around them. The aim of ST is therefore to understand how the person has made sense of their world and their life experiences, providing corrective experiences where needed, which can create transformative change and growth.

Young’s model comprises 18 Early Maladaptive Schemas (EMS) each of which consists of cognitions, emotions, memories and bodily sensations which can be activated (or ‘triggered’) by everyday events or experiences, often outside of our conscious awareness. This results in that event/experience being dominated by the intense feelings and dysfunctional thoughts associated with the schema.

To manage this, people respond by using a coping response of:

- surrender – where the person gives in to the schema and acts in ways which affirm its truth

- avoidance – where the person avoids activities which may trigger the schema and related negative emotion, and

- overcompensation – where the person tries to disprove or counteract the schema by acting in the opposite direction predicted by the schema.

Our coping responses were adaptive for survival at one time but may no longer be helpful to a person’s life.

Schema modes are moment-to-moment emotional states which reflect activated clusters of cognitions, emotions and behaviours and the resulting interaction between the schemas and coping responses. Schema modes can be unhelpful and can, to differing degrees, be cut off from other parts of the self, which can result in rigid and inflexible behaviour. A schema is considered more like a ‘trait’ and a schema mode is a ‘state’. The ST model currently conceptualises parent/critic modes (e.g., the ‘punitive parent’ mode), child modes (e.g., ‘vulnerable child’ mode), coping modes (e.g., the ‘detached protector’ mode) and the ‘healthy adult’ mode.

ST is particularly effective for characterological problems, which occur when individuals lack psychological flexibility and self-destructive patterns become a large part of who they are (Young et al., 2003). This description is central to the experience of Defence personnel and their inability to identify themselves outside of the military. They have made sense of themselves and the world through a military lens and cannot imagine changing or letting go of this view. To understand this further I have developed the military mode model.

The military mode model

Soldiers are generally recruited at age 17–25. Psychologically, this is a key developmental period when people are defining their identity and evaluating beliefs about themself, others and the world around them (Mobbs & Bonanno, 2018). During recruit training, the Defence Force socialises individuals into the culture, providing a military identity and community for the individual to belong to and to provide concrete answers to existential questions (Mobbs & Bonanno, 2018). This identity serves the organisation, creates group cohesion and allows personnel to do their job without conscious thought, and prepares them for acts of war such as killing (Mobbs & Bonanno, 2018). In schema terms, this can be conceptualised as a ‘military mode’, which is a learned coping mode that is adaptive for service in the Defence Force, particularly operational and/or combat service.

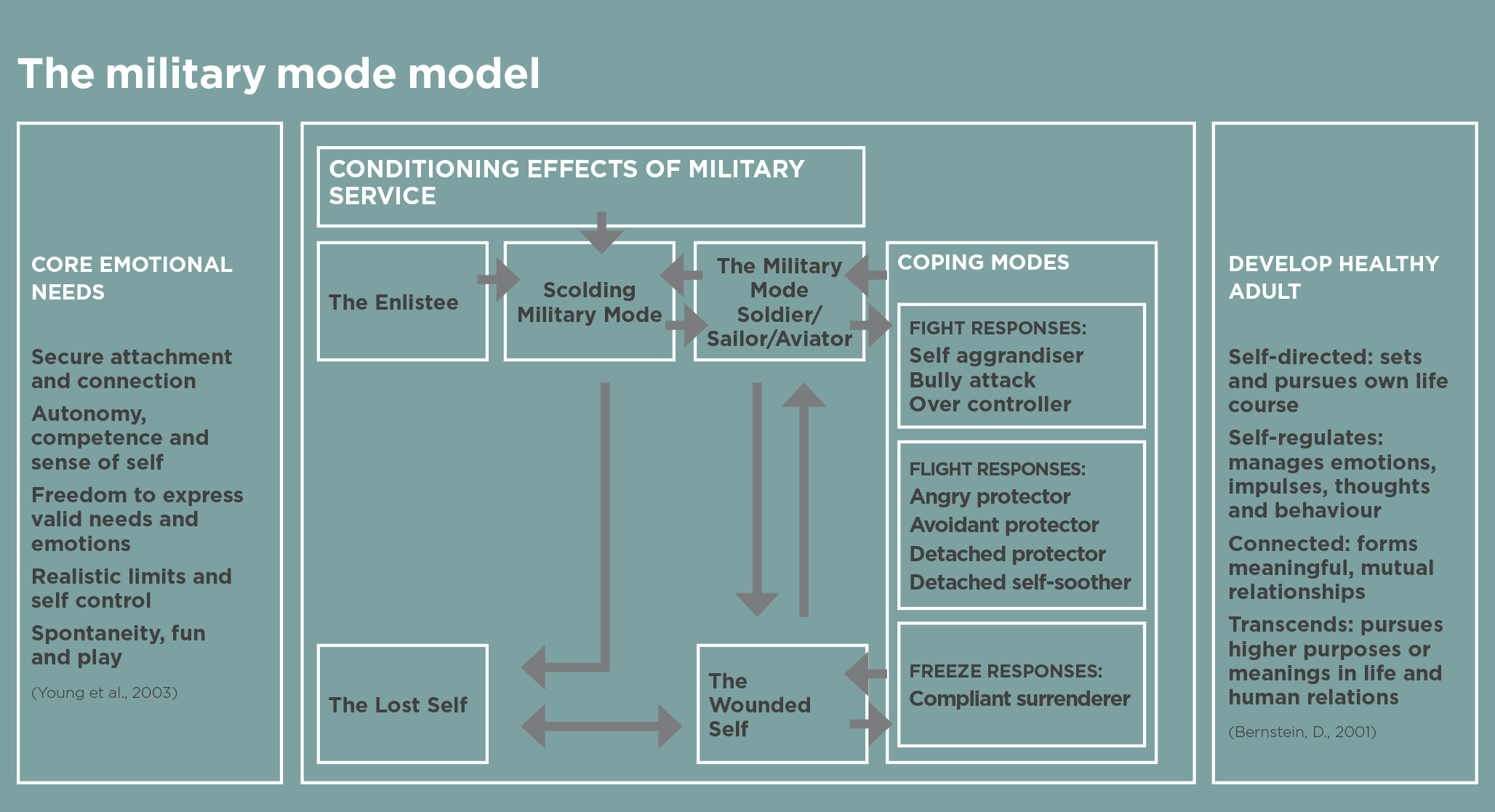

The figure is a representation of the ‘military mode model’, including how it develops, creates difficulties at transition and the implications for management. On the left-hand side are the core emotional needs central to schema therapy. ‘The enlistee’ comes from a diverse range of backgrounds, where their underlying core needs have been met to varying degrees. As there is a high prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in military personnel (Duel et al., 2019), it could be proposed that people entering the military have a range of early maladaptive schemas (EMS), which may attract them to the military.

The central section of the figure describes the military conditioning process. To socialise the enlistee to the military and address the individual factors and the way the enlistee has already learnt to cope with life experiences to date, the military disconnects and discards the self prior to the military (the lost self). Whoever the enlistee was before, and whatever has happened previously, is now irrelevant because they are in the military.

How it operates

The military mode is conditioned through the ‘scolding military mode’, which is the equivalent of the parent/critic mode in ST. The scolding military mode uses fear and shame tactics to activate emotions to change the way the military person responds in any given moment, to create a task-focused action response that serves the organisation. It discourages weakness and vulnerability; demands that military standards and expectations are met; focuses on performance and achievement; enforces group cohesion and teamwork, and it channels anger for controlled aggression.

As such, the military operates like an authoritarian family system that fosters a sense of belonging (through performance) and enforces the military values and beliefs, to align a person’s belief system and behaviour with that of the military. Over time these beliefs and behaviours become rigid, enmeshed and inflexible.

For most enlistees, by the end of basic training the military mode is created and provides an identity, meaning and purpose for the individual. The military mode is the ‘soldier’, ‘sailor’ or ‘aviator’ part of themselves that feels strong, tough, resilient, adaptable, task-focused, efficient, achievement-orientated, compliant, respectful, confident, capable and calm under pressure; who has controlled aggression, is a team player and proud of who they are and what they do.

The military mode is adaptive for service, as it will enable the enlistee to successfully serve the organisation (surrender coping), detach from emotions (avoidant coping) and do whatever it takes to complete the task and achieve the desired outcome (overcompensation coping). Service in the military can meet core emotional needs by generating a feeling of security, belonging, connectedness and competence, particularly when the group achieves the standard required. For some, this is the first time that they have ever experienced these feelings and it can feel empowering, safe and secure. This strengthens the attachment and enmeshment with the military identity and the organisation.

The military operates like an authoritarian family system that fosters a sense of belonging and enforces the military values and beliefs

Adverse psychological impacts of the military mode

Due to the military standards and expectations, you are only accepted and belong if you can perform. However, people in the military experience physical, emotional, family or other issues during service, resulting in the military mode armour getting penetrated by life circumstances, which creates the ‘wounded self’ and potentially results in the person having to discharge (voluntarily or involuntarily) from service. The wounded self is the part that holds the accumulated unprocessed emotions and any pain or difficult experiences encountered because of service and it is linked (to varying degrees) to the ‘lost self’ (the part discarded at basic training).

If there was early-life trauma, schema perpetuation and activation of the lost self will likely be more predominant and significant. The wounded self is the equivalent of and deeply connected to the vulnerable child mode in ST, often with core schemas linking the two modes. Military personnel do not like to be vulnerable, wounded or to have emotion, so they try to stay in their military mode.

What happens at transition?

After military service, a natural personal growth period is important for the individual to develop their own identity and sense of self in the civilian community. However, the military mode disrupts this process because of (1) disconnection, and (2) an underdeveloped and enmeshed sense of self, which both impact the individual’s ability to function in the civilian world and undergo this natural growth process. This creates psychological distress, particularly feelings of being lost and confused. There is likely to be an absent or weak healthy adult mode because the central organising function for the individual is through the military mode.

Whilst some aspects of this mode can be adaptive in the civilian community (e.g., task-focused, driven, efficient), the rigidity impairs the flexibility required to make best use of relevant military skills and attributes. Also, the military mode is perceived to be superior to a civilian and military personnel tend to believe that civilians should adapt to their way of doing things, particularly in relation to efficiency and performance. Therefore adjustment into the civilian community can feel like ‘a stepping down’, perpetuating feelings of disconnection, confusion, frustration, and being lost.

This in turn results in the person using other types of maladaptive coping modes to protect themselves and maintain functioning, creating a self-destructive coping mode cycle as presented in the model. Typically, I see people (1) relying on self-soothing or thrillseeking activities to avoid emotions; (2) trying to control others and the world around them to overcompensate for feelings of fear, shame and guilt; and (3) subjugating in their relationships to surrender and prioritise others. This cycle is maintained by the scolding military mode, the desire to stay in the military mode, fears of abandonment and rejection and for some the fear of the ‘lost self’.

How schema therapy can help

The goal of ST is to break this cycle of survival and develop the healthy adult. This involves the person making sense of their experiences, and learning about their core emotional needs and how to adaptively meet these in civilian life. They need to learn how to be self-directed; how to understand and regulate their emotions, impulses, thoughts and behaviour; how to connect (to themselves, others and the community); and how to transcend after they leave the military. With my conceptualisation, ST encourages a process of connection and growth by identifying and understanding the pre-military self, the military self and the developing now self. It fosters psychological flexibility and autonomy, thereby facilitating transition.

ST is particularly effective for addressing chronic pervasive problems in hard-to-treat populations, such as people with personality disorders, with interventions demonstrating low attrition rates and high recovery rates (Taylor et al., 2017). One study demonstrated greater reductions in PTSD and anxiety symptoms among male Australian and New Zealand Vietnam veterans who received ST, compared to those who received traditional CBT (Cockram et al., 2010). This innovative and theoretically schema-based perspective of the psychological impacts of service provides both a preventive and restorative pathway to facilitate transition.

Where to from here?

Understanding more about what attracts people to the military and how the military impacts the person can assist us to improve psychological services for veterans. I have briefly showed how ST can help this process. Using this model with clients can create important discussions about the psychological impacts of service and awareness of the self prior to military service, their military self and their developing now self. I am currently investigating the role of schemas in transitioned military personnel and the potential impact of a ST group program (developed in clinical practice) to assist military personnel transition after service. My hope is that such a program is made widely available and accessible at transition, to facilitate post-military growth.

Contact the author: [email protected]

For a PDF of the official military mode model, visit bit.ly/3mOxe7a

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my advisors: Professor Shirley Morrissey, Associate Professor Nicola Burton and Dr Mark Boschen for their support, encouragement, mentoring, guidance and feedback with my research and this article. I would also like to thank all of the veterans who have worked with me to develop and provide feedback on the military mode model. I would like to thank my colleagues, in particular John Guimelli, who has great passion for this work and supports myself and our veterans to conduct the group programs. I would like to thank my family for their endless support and patience with my work.