The introduction of Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) items for eating disorders in November 2019 has generated increased interest in eating disorders and their treatment. While the new MBS items target anorexia nervosa, severe bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder (and similar), it is likely that the increased attention to eating disorders in primary care will facilitate improved treatment seeking and identification, and therefore an increased need for effective treatment across the range of eating disorders. This article is intended to provide updated information about the diagnosis, prevalence and prevention of eating disorders, as well as detailed information about evidence-based assessment and treatment. The increased support for eating disorder treatment will provide opportunities for more clinicians to work with individuals with eating disorders. This will require clinicians to review their own competence and evaluate their scope of practice. To assist with this the article ends with a review of the National Eating Disorder Collaboration (NEDC) National Practice Standards for Eating Disorders and the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Eating Disorders (ANZAED) Mental Health and Dietetic Clinical Practice and Training Standards, and a brief summary of planned NEDC and ANZAED credentialing activities.

With the introduction of the fifth edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), a number of changes were introduced to eating disorder diagnostic criteria. The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are now more inclusive (e.g., less frequent binge and compensatory behaviours), and binge eating disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) are included as distinctive diagnoses. As a result, some of those previously diagnosed with eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) may now meet criteria for one of the above disorders. Alternatively, they may be diagnosed with other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED; see below, or an unspecified feeding or eating disorder (USFED; clinically significant feeding or eating disorders that do not meet the criteria for another eating or feeding disorder). Prevalence

Prevalence

A 2012 review of population-based studies of eating disorders in Australia estimated that approximately four per cent of the Australian population had an eating disorder. Based on these findings it is estimated that more than a million Australians had an eating disorder in 2019. This included 0.11 per cent with anorexia nervosa (AN), 0.47 per cent with bulimia nervosa (BN), 1.87 per cent with binge eating disorder (BED), and 1.53 per cent with eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS was used in this study so comparisons could be made to 2012 data) (Deloitte Access Economics, 2019). See box opposite for prevalence rates estimated using more recent data and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Many more people experience disordered eating (i.e., behaviours consistent with an eating disorder (e.g., restrictive dieting, binge eating, vomiting, laxative use) that do not meet criteria for an eating disorder (Hay et al., 2017).

Consequences

Eating disorders are associated with a range of medical complications, in addition to the psychological distress and impairment. Eating disorders can have cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, neurological and endocrinological consequences. Individuals with an eating disorder are at increased risk of psychological distress and psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety), and impaired physical and mental health related quality of life. They are also at greater risk of self-harm and suicide. Combined these consequences result in a significant physical, psychological, social, economic and community burden.

Prevention

Several programs have demonstrated success in the prevention of eating disorder risk factors. Universal prevention programs including media literacy, multicomponent interventions and healthy weight interventions can improve eating attitudes, weight and shape concern, and unhealthy weight control behaviours. Effective selective prevention programs include cognitive dissonance, multicomponent interventions, mindfulness and psychoeducation. There is also evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive behaviours preventionearly interventions targeting individuals showing early signs of eating disorders. Importantly, research shows that prevention programs can increase the risk of eating disorders. Content that overtly discusses eating disorders/disordered eating, labels food and eating patterns as good/bad, and/or increases weight or shape concerns is associated with increased risk of disordered eating and eating disorders (National Eating Disorders Collaboration, 2020).

Seeking treatment

Unfortunately, many people with eating disorders do not access treatment and even fewer access treatment consistent with clinical guidelines. This can be attributed to an individual’s unwillingness to seek treatment, as well as the lack of screening and identification, and limited treatment options. A review of studies examining the unmet need for eating disorder treatment reported that the majority of individuals with eating disorders believed they needed treatment, some sought treatment, and only a minority accessed treatment.

This review determined that 77 per cent of eating disorder cases had an unmet need for treatment. In this review, the 23 per cent who were accessing treatment included those accessing treatment from a range of medical, health and mental health professionals and/or self-help treatment. The studies assessing mental health treatment reported that between 0 to 16 per cent of participants were accessing mental health treatment. Of concern, individuals with eating disorders were more likely to access medical treatment for weight loss, which is not indicated in the treatment of eating disorders (Hart, Granillo, Jorm, & Paxton, 2011).

Assessment

Clinical interview is the optimal method of eating disorder assessment and diagnosis. A comprehensive assessment should include the presence and history of eating disorder symptoms and psychiatric comorbidities. The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) is the gold-standard clinical interview for the assessment and diagnosis of eating disorders. It is rarely used in full in clinical practice, but can provide a guide for eating disorder assessment. A range of validated self-report questionnaires exist for the assessment of eating disorders. The Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) is based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview and is commonly used for screening and assessment. Australian norms are available, and it is the required assessment tool for the new MBS items for eating disorders.

The EDE-Q asks about the previous 28 days and includes behavioural frequency measures (e.g., vomiting, bingeing, restriction), and four subscales assessing cognitive factors (Restriction, Eating concern, Weight concern, Shape concern) that can be combined to create a global score. As well as being useful pre- and post-treatment, the EDE-Q can also be used throughout treatment to facilitate ongoing evaluation. Given the impact that eating disorders can have on physical health, a medical assessment is also required. The National Practice Standards for Eating Disorders (NEDC, 2018) and the Australia and New Zealand Academy for Eating Disorders (ANZAED) Mental Health and Dietetic Clinical Practice and Training Standards for the Treatment of Eating Disorders provide more information about eating disorder assessment (ANZAED, 2020).

Treatment

Treatment

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) clinical practice guidelines for treating eating disorders provide recommendations for treating anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, OSFED and USFED (Hay et al., 2014). The guidelines are consistent with the Australian Psychological Society College of Clinical Psychologists review of evidence-based approaches for eating disorders (Wade, Byrne, & Touyz, 2013). The RANZCP make the following treatment recommendations.

Anorexia nervosa

- Interdisciplinary treatment (i.e., nutrition, medical, psychological)

- Long-term specialised therapist-led manualised psychological treatment

- Family-based therapy for young people

- Hospitalisation only when required to manage medical or psychological risk

Bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder

- Cognitive behavioural treatment for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder

- Guided self-help cognitive behaviour therapy

- Pharmacotherapy (e.g., antidepressant, topiramate) as an adjunct or alternative treatment

The NEDC Evidence Review of the Prevention, Treatment and Management of Eating Disorders (National Eating Disorders Collaboration, 2020) provides a review of the evidence regarding the treatment of eating disorders. Interventions were evaluated based on the level of evidence and the magnitude of the treatment effect. The table below summarises the results for all interventions with substantial1 magnitude of effect, as well as those with moderate2 to substantial3 evaluation, demonstrating moderate 4 to substantial magnitude of effects.

What does the evidence say?

Anorexia nervosa in young people

Family-based treatment (Maudsley therapy) has been subjected to a moderate degree of evaluation, and its magnitude of effect is substantial. This is a specific form of family therapy that focuses on weight gain and supports the family to take control over the young person’s eating until they are well enough to do this themselves.

Anorexia nervosa in adults

No treatment demonstrated substantial effects. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders5 has been subjected to a substantial degree of evaluation, and its magnitude of effect is moderate. It aims to modify the unhelpful behaviours and thinking patterns maintaining the eating disorder. It targets eating disorder behaviours (e.g., dietary restriction, overexercising) and cognitions (e.g., weight and shape concerns, diet rules) and may address broader maintaining factors (e.g., perfectionism).

Psychodynamic/psychoanalytic and specialist supportive clinical management each demonstrate moderate evaluation and moderate magnitude of effect in the treatment or anorexia nervosa in adults. Psychodynamic/psychoanalytic therapy does not directly address the eating behaviour or symptoms, instead treatment focuses on the conscious and unconscious meaning of the illness with the aim of improving insight into the illness. Specialist supportive clinical management includes education, care and supportive psychotherapy encouraging normal eating patterns and weight restoration.

Adults with bulimia nervosa

Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders has been subjected to a substantial degree of evaluation, and its magnitude of effect is substantial. It aims to modify the unhelpful behaviours and thinking patterns maintaining the eating disorder. It targets eating disorder behaviours (e.g., dietary restriction, purging) and cognitions (e.g., diet rules) and may address broader maintaining factors (e.g., interpersonal functioning). Cognitive behaviour therapy guided self-help has been subjected to some degree of evaluation, and its magnitude of effect is substantial. This involves cognitive behaviour therapy provided largely in a written format with brief, regular sessions with a therapist who provides monitoring and support. Exposure therapy has been subjected to a moderate degree of evaluation, and its magnitude of effect is moderate. It uses graded exposure to triggering foods and situations and response prevention to reduce bingeing and purging.

Adults with binge eating disorder

Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders has been subjected to a substantial degree of evaluation, and its magnitude of effect is substantial. It aims to modify the unhelpful behaviours and thinking patterns maintaining the eating disorder. It targets eating disorder behaviours (e.g., dietary restriction, bingeing) and cognitions (e.g., all or nothing thinking) and may address broader maintaining factors (e.g., emotion regulation). Dialectic behaviour therapy demonstrates substantial evaluation with moderate magnitude of effect. It targets tolerance and management of emotions involved with the eating disorder. Interpersonal psychotherapy demonstrates moderate evaluation with moderate magnitude of effect. It targets interpersonal issues involved in the development and maintenance of the eating disorder.

There is considerable clinical interest in the use of third-wave behavioural therapies for the treatment of eating disorders and disordered eating. A 2017 review (Linardon, Fairburn, Fitzsimmons-Craft, Wilfley, & Brennan, 2017) of the empirical status of third-wave therapies for the treatment of eating disorders in adults (16 years and over) found that while third-wave therapies demonstrated pre-post intervention symptom improvements, they were not superior to cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders, and none of the third-wave therapies met criteria for empirically supported treatments for specific eating disorders (as defined by Chambles & Hollon, 1998). Combined, these results indicate that, while third-wave behaviour therapies may be effective eating disorder treatments, further research examining their efficacy and effectiveness is required. Based on currently published research, cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders continues to be the first-line treatment for eating disorders in adults.

Competencies for psychologists

Competencies for psychologists

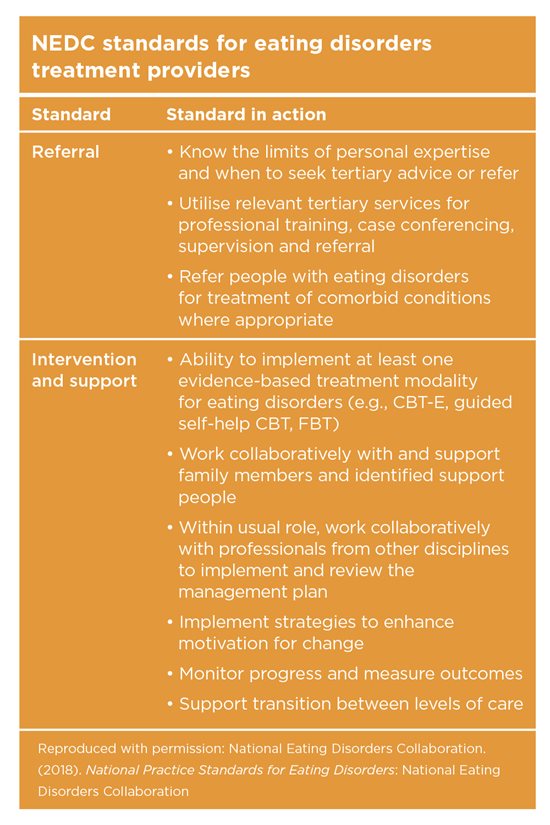

The NEDC (National Eating Disorders Collaboration, 2018) provide guidelines regarding core competencies for professionals involved in identification, screening, assessment/diagnosis, referral, treatment and recovery support for individuals with eating disorders.

The standards for treatment providers are particularly relevant to psychologists providing treatment for eating disorders. The standards cover knowledge (e.g., describe the medical care that may be required to treat eating disorders, describe the range of evidence supported treatment modalities for eating disorders), assessment (e.g., contribute to the comprehensive assessment of individuals with eating disorders and take a clinical history using culturally appropriate practice), referral (e.g., know the limits of personal expertise and when to seek tertiary advice or refer) and intervention and support (e.g., ability to implement at least one evidence-based treatment modality for eating disorders). Please see the guidelines for details of the Knowledge and Assessment Standards.

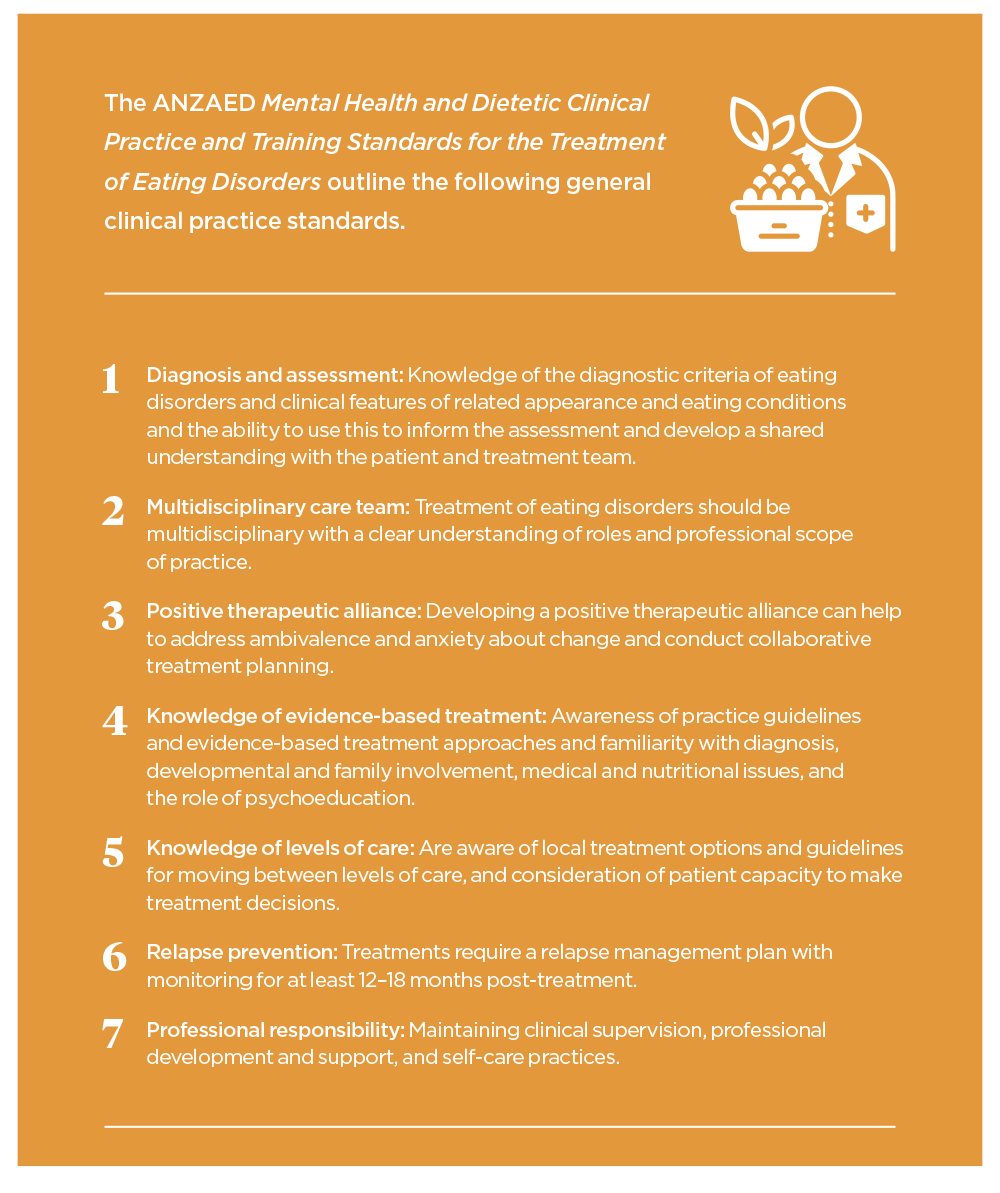

Building on these eating disorder core competencies, ANZEAD developed the Clinical Practice and Training Standards for Mental Health Clinicians and Dietitians Providing Eating Disorder Treatment. The final version of this document is due for publication later this year. The following information is based on the draft standards which were made available for feedback in 2019.

Training standards for mental health clinicians and dietitians offering eating disorder treatments will also outline dietetic-specific and mental-health-specific clinical practice standards and describe the criteria for assessing relevant training programs that provide eating disorder education.

Both the NEDC and the ANZAED standards highlight the need to operate within scope of practice, and the importance of eating disorder specific training, supervision and ongoing professional development. ANZAED and other professional groups are offering a range of training, supervision and professional development opportunities to facilitate workforce development in eating disorder assessment and treatment.

Credentialing

The NEDC and ANZAED recently announced their intention to develop a credentialing system for eating disorder treatment professionals in Australia to support an effective, competent and connected workforce. This credentialing system will recognise skills and competence in evidence-based treatment. The NEDC and ANZAED, with the support of the Alliance of Eating Disorder Consumer and Carer Organisations, are currently working to identify the optimal way to design and implement a credentialing system. There will be opportunities for consultation early in 2020.

The first author can be contacted at [email protected]

1 Substantial and persistent effects

2 Level 2 (well-designed randomised controlled trial) and/or Level 1 (systematic reiew of randomised controlled trials) and/or Level 2 evidence available

3 Two Level 1 studies

4 Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders is a specific form of cognitive behaviour therapy (e.g. Fairburn, 2000)