Academics serve a unique and irreplaceable role in many professions. They provide the connection between the profession and the students who will provide the future workforce. The current situation in the Australian higher education sector has produced a ‘perfect storm’ for academics and has dramatically changed the landscape. In this volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) environment there are certain strategies that may enhance and maintain academics’ wellbeing. These would complement the growing emphasis on student wellbeing. The two issues are closely linked and should be considered as one of the key priorities for all higher education providers (HEPs).

A recent report in the journal Nature (13 November, 2019) revealed a large proportion (36%) of current graduate students who responded to their survey (6,300 graduates) reported seeking help for anxiety or depression. This help was often sought within their institution (43%) but was only helpful to 26 per cent of respondents. The majority of respondents (77%) were in the 25 to 34 age group, with 78 per cent reporting no caring responsibilities (either children or adult). This is a very concerning early indicator of the levels of mental health issues that these future academics may experience.

The Students Transitions Achievement Retention & Success conference (STARS, 2019) featured a range of papers and sessions about students’ wellbeing, confirming that this has become one of the most important issues for all HEPs. In addition, STARS 2019 included a forum focused on university staff wellbeing called Fitting Your Own Oxygen Mask First. It was clear that the panel was aware of the increasing demands on academics but also unsure what strategies would be helpful. Should we be focusing on the self-care message implied in the title? Should we be looking at the workloads of academics and how to better manage these? Should we focus on the organisational environment and structures that could facilitate better wellbeing (i.e., whether the workplace could also offer systemic mental health interventions)?

Workplace culture

There needs to be a systematic approach to enhancing both academics’ and students’ wellbeing and this means focusing on creating a culture of wellbeing. Building a culture of wellbeing involves giving equal priority to individuals’ health and wellbeing as to the organisation’s health and wellbeing. This type of culture facilitates individual and organisational growth and development, and where both of these goals are fulfilled, a sustainable and uplifting workplace culture will exist. While the strategies and resources to build a culture of wellness may already be present, the driving force in producing the best possible outcomes is the quality and type of leadership demonstrated throughout the HEP.

The security of academic work is also threatened and this can undermine academics’ wellbeing. The National Tertiary Education Union State of the Uni Survey (2015) captured the views of approximately 7,000 Australian academics and professional staff. A majority of academic staff (50.7%) disagreed (or strongly disagreed) with the statement “My job feels secure”. Even greater numbers of academics disagreed (or strongly disagreed) with the statements “I am consulted before decisions that affect me are made” (66%), and “Workplace change is handled well at my institution” (68.3%).

With respect to the type of employment, academics who are fixed-term or on casual contracts (33.2% of respondents) reported that job security, income security and career development were the three most important areas impacted by their insecure work. Most of these respondents (76.8%) reported that they would prefer permanent work which was either full- or part-time. Many (22.4%) worked at two or more universities.

Health and wellbeing projects

Given the importance of the academic work environment as a contributor to the levels of wellbeing and as a potential site for interventions, academics at several institutions (including the University of Southern Queensland) have worked on several projects with a health and wellbeing focus in a range of organisational settings.

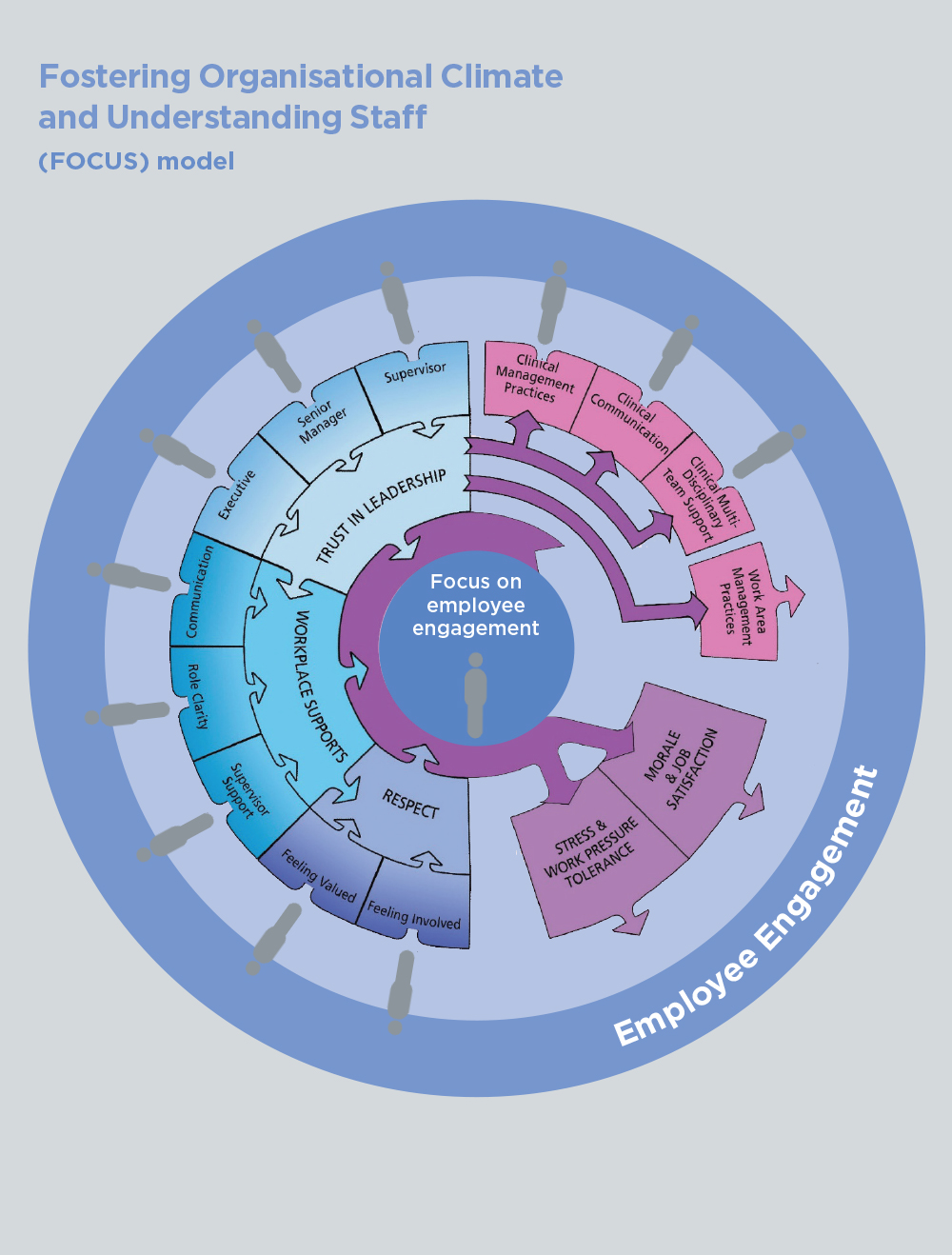

One of these was the development of the first Queensland Health Better Workplaces Staff Opinion Survey (BWSOS; Jury et al., 2009). This project led to a new organisational survey and underpinning model called FOCUS (Focus on Organisation Climate and Understanding Staff – below – which captures the key dimensions).

One of the outcomes was a measure we called the Respectful Workplace Scale. As outlined by Fogarty (2011), a respectful workplace incorporates a number of practices such as:

- being kept informed

- personal respect

- personal safety

- appreciation and recognition, and

- fair work practices.

Not surprisingly, all of these measures are moderately related to each other reflecting their common root. Therefore, we constructed a brief 10-item scale to measure overall workplace respect, with items such as:

- the staff I work with treat me with respect

- communication between management and staff is open and transparent

- my work is appreciated and acknowledged.

The FOCUS model mirrors the work conducted by Maureen Dollard and colleagues at the University of South Australia on psychosocial safety climate (PSC). PSC captures the organisation’s commitment to the employee’s wellbeing and safety and directly influences the work context (Dollard & Bakker, 2010). A measure of PSC (the PSC-12), has four sub-scales, which assess levels of management commitment, management priority, organisational communication and participation (Hall, Dollard, & Coward, 2010). This measure is now incorporated into the Australian Workplace Barometer (AWB) project which provides a comprehensive assessment of work-related factors and employee psychological health and wellbeing.

Building a respectful workplace must involve middle managers in developing sensible strategies about how to approach issues that relate to employees’ safety, health and wellbeing. Tinline and Cooper (2016) offer middle managers many strategies for succeeding in their roles. In particular, they adopt a ‘whole person’ perspective that includes all important life roles. Whether you subscribe to a healthy work-life balance, a positive work-life integration, or a flexible approach to managing work and non-work demands, the key seems to be to consider all aspects of your life when planning how to maintain your health and wellbeing.

Building a healthy culture

Given the importance of maintaining a respectful work climate, there is a great need for interventions which improve the levels of civility and respect at work. The one which has shown the most promising results is CREW (Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the Workplace; Leiter, 2013). This intervention focuses on the interpersonal processes occurring at work and on establishing agreed norms for civil interactions in the workplace. There are many benefits to studying the antecedents and consequences of civil interactions in an academic context as a tension exists between an academic’s right to speak freely about important matters and the need to remain civil.

Cortina, Cortina, & Cortina (2019) recommend that academics set ground rules in all meetings and colloquia, not just in the classroom. Further, acts of kindness should be recognised and rewarded, while contempt and mockery strongly discouraged. They also state that it is important to ensure that the academic ‘rock stars’ are held to the same standards of behaviour as other staff. Other strategies that are being used in a number of organisations which seem to offer benefits for academics in terms of their wellbeing include flexible work arrangements (FWAs), and job crafting.

The demands for greater work/non-work integration are central to the life of an academic where work can occur away from the workplace, outside of traditional working hours and may not constitute a full-time workload. Flexible work arrangements or flexible work options (FWOs) are available to academics in Australian HEPs according to the Fair Work Act 2009 and the individual enterprise agreements at each HEP.

However, merely having access to FWOs does not ensure that employees will actually take advantage of these. A study by Albion (2004) which included non-academic staff from a regional university reported that perceptions of the importance of having a work/family balance were a stronger predictor of the use of FWOs than perceived barriers to using FWOs. In order to ensure that FWOs are not a source of disruption to academics’ work/life balance, supervisors must be supportive of these arrangements. A recent systematic review of family-supportive supervisor behaviours (FSSBs) highlighted the important role of supervisors in creating a work/life balance (Crain & Stevens, 2018). Academics may need to be more proactive in seeking FWOs in order to maintain their wellbeing during more demanding life stages and supervisors play an important role in ensuring that these arrangements are effective.

Academic roles are often a portfolio of different tasks each with its own set of demands and resources. Careful application of job crafting can assist in producing the best fit between academics and their diverse roles. Job crafting is defined as “the changes to a job that workers make with the intention of improving the job for themselves” (Bruning & Campion, 2018, p. 500). While there is still debate about the construct, Zhang and Parker (2018) have provided a framework that includes two different foci (approach and avoidance), which may involve two different strategies (behavioural and cognitive), which can also be resource-focused or demands-focused. These combinations allow for a wide range of strategies to be deployed by academics seeking to optimise their roles and improve their wellbeing. Job crafting allows individuals to focus on their strengths and reshape their role over time. We should recognise that academic roles are likely to be diverse as academics engage in crafting their roles.

Promoting future wellbeing

What else is needed to enhance the wellbeing of academics in higher education? Every aspect of academic life is being scrutinised and is subject to a metric. How many citations have you had for your research? How much income have you received? How did your students rate their learning in your classes? How many likes (or retweets) did your tweets receive? How have you contributed to your institutions engagement and impact in the community?

There is a major problem with only using lagging indicators when measuring the performance of academics. Many organisations are now looking for the leading indicators which better represent their investment in occupational health and safety, including employees’ wellbeing. It would be a major step forward to have leading indicators which are focused on the factors contributing to academic wellbeing. These could include measures of the visibility and importance of initiatives focused on academic (and employee) wellbeing, measures of the level of involvement of academics (and other staff) in developing policies and addressing issues about wellbeing, and measures of the availability of resources and support for employee wellbeing. Not surprisingly, these kinds of indicators are already part of structured assessment tools developed to assist organisations to improve their occupational health, safety and wellbeing (Shea, De Cieri, Donohue, Cooper & Sheehan, 2015).

While the future presents some major challenges in this area, the value of a systematic approach to enhancing academic employees’ wellbeing would be enormous, particularly in minimising the psychosocial risk factors that contribute to mental ill-health, and poorer work engagement. Organisations are better equipped to maintain and enhance academics’ wellbeing through the psychological research which has been cited here as well as the example of leaders who demonstrate a strong commitment to a workplace culture that prioritises wellbeing. Academic leadership that is health-focused, authentic and engaging has never been more important.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]