The exact number of Australians undergoing cosmetic procedures is unknown, but there is a consensus that demand is on the rise. This is an international phenomenon and there are various factors, social and personal, that may be contributors to someone choosing to undergo a cosmetic procedure. Along with the demand, there has been an increase in attention from researchers and clinicians in the benefits and risks of cosmetic surgery, particularly for some population groups.

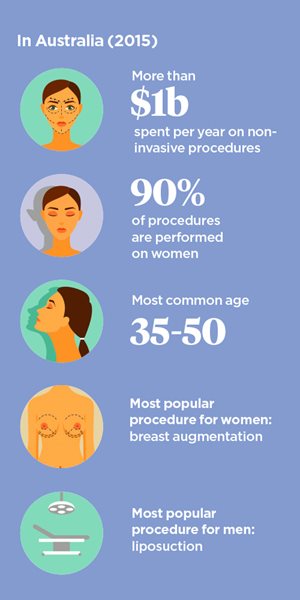

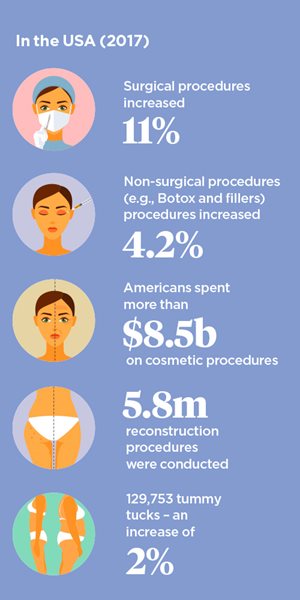

In the USA, where procedure numbers are publicly reported, surgical procedures increased 11 per cent in the last year alone and non-surgical procedures (e.g., Botox and fillers) increased 4.2 per cent, resulting in a spend of over 8.5 billion dollars in total. In a rare survey conducted in Australia in 2015 by the Cosmetic Physicians College of Australasia, Australians were spending more than 1 billion dollars a year on minimal or non-invasive cosmetic procedures. Approximately 90 per cent of cosmetic procedures are performed on women and the most common age for individuals to undergo a procedure is between 35 and 50 years. Breast augmentation continues to be the most popular cosmetic surgery for women and liposuction for men.

Factors driving demand

A number of reasons have been proposed to explain the increased demand for cosmetic procedures. Broadly speaking, cosmetic procedures have become more affordable and with higher disposable incomes, these procedures have become attainable to more people. Also, advances in wound care and post-operative healing have made procedures safer and thus more appealing for patients. These improved features of safety and affordability continue to be used to directly market cosmetic procedures to consumers through various media channels.

There are also the broader impacts of mass media. Television, movies, magazines and music videos all portray images of what we should look like. They provide us with our societal standards for beauty. The issue is that the majority of people will never be able to naturally attain the extreme standard of beauty shown in the media and so cosmetic procedures present a method of potentially fulfilling these beauty ideals. Cosmetic surgery was the focus of several reality TV programs in the 2000s, such as The Swan and Extreme Makeover. Research showed that women who viewed these shows tended to have more positive views about cosmetic surgery and stronger consideration of surgery for themselves.

These shows also served to normalise cosmetic procedures. Media exposure can shape our perception of social reality often without our awareness. With continued exposure over time, our attitudes may be modified such that cosmetic surgery is now viewed as an acceptable body modification method rather than something shameful. We now also have the influence of social media which is potentially the most pervasive form of all media. As far as I am aware, there have been no in-depth investigations of the impact of exposure to social media on cosmetic surgery consideration specifically, but there is evidence to suggest that social media use may enhance body image concerns which, in turn, could potentially lead to increased interest in cosmetic procedures.

Dysmorphia and dissatisfaction

Dissatisfaction with body image is thought to be the main driving factor behind cosmetic procedure requests. Body image can be defined as the notion of one's physical appearance based on self-observation, emotions, physical sensations, and the response of others to our bodies. Sadly, the majority of people in the wider community are dissatisfied with their body image. However, people who seek cosmetic procedures experience even greater body image dissatisfaction than population norms. Importantly, this dissatisfaction is usually specifically focused on the feature for which the cosmetic intervention is sought rather than a global body image dissatisfaction.

Severe body image dissatisfaction is a key feature of several formally recognised psychiatric disorders. The most studied and assumed to be most prevalent in cosmetic populations is body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). The prevalence is estimated at between 1 and 3 per cent of individuals in the general community but between 5 and 15 per cent in cosmetic populations, regardless of the procedure. In short, the diagnostic criteria for BDD, according to DSM-5, are a preoccupation with one or more perceived flaws in physical appearance which are not visible or are minor to other people. In response to these concerns about appearance, the individual will perform repetitive behaviours (e.g., checking body parts in the mirror) and mental acts (e.g., comparing appearance with other people). These concerns have a significant negative impact on the individual's daily functioning in important life domains. It is understandable that individuals with BDD will seek out cosmetic interventions to address concerns with their physical appearance in an attempt to alleviate their distress.

Body dysmorphic disorder DSM-5 criteria

- Preoccupation with appearance or flaws that are not visible or appear minor to others).

- Repetitive behaviours in response to appearance (e.g. excessive mirror checking or/grooming, comparing appearance to others).

- The preoccupation causes clinically significant distress and impacts on daily function.

|

Feedback from those around us (peers, partners, family) also has an impact on desire to undergo cosmetic interventions. Being teased or receiving negative feedback on our physical appearance during childhood and adolescence has an overall negative impact on body image satisfaction and predicts interest in cosmetic procedures. Through changing our appearance to conform to society's beauty ideals, this negative feedback may even turn into positive feedback.

This discussion is by no means an exhaustive list of the factors that influence people to undergo cosmetic procedures. Motivations for cosmetic intervention are often complex and multi-faceted. Recent studies involving in-depth exploratory interviews with cosmetic patients are adding to the knowledge we have gained from more standardised questionnaire studies. For example, some individuals may be seeking cosmetic intervention to assist them cope with recent difficult life events such as a breakdown of a relationship. These kinds of interviews allow us to gain a broader, less static understanding of the person including their personal background and development.

Risk factors

The research in the area of risk factors for cosmetic procedures is particularly limited and suffers from methodological shortcomings. However, the findings to date suggest that: (1) certain demographic factors, (2) unrealistic expectations, (3) relationship issues and (4) mental health issues are associated with poorer procedural outcomes.

- Being male and younger (i.e., less than 40 years) have been associated with lower satisfaction with cosmetic procedures. A commonly used acronym amongst plastic and cosmetic surgeons is 'SIMON' to describe younger male patients who are 'obsessive' or 'hung up' on a particular physical feature. SIMON stands for Single and Immature Male who is Overly expectant and Narcissistic. This acronym appears to be derived more from clinical experience than rigorous research.

- Patients with unrealistic expectations are also frequently dissatisfied. These unrealistic expectations may be focused on the patient's own psychological wellbeing or broader life domains. Some patients may have an exaggerated expectation that having a procedure will revolutionise their lives, particularly in their intimate relationships and career.

- Individuals who have been strongly influenced or coerced into having the procedure by a partner or family member rather than themselves being the motivator tend to have poorer outcomes. Moreover, seeking cosmetic procedures to 'save' a troubled romantic relationship often results in disappointment.

- Certain mental health presentations such as mood and eating disorders are thought to be over-represented in individuals who seek cosmetic interventions, but the most commonly investigated mental health disorder in this population is BDD. A number of studies have shown that almost all individuals with BDD who undergo cosmetic intervention do not improve or their symptoms worsen. After treatment, new appearance concerns can develop thus maintaining the BDD. Even more concerning is the high rate of suicide amongst individuals with BDD, which may be exacerbated after a disappointing cosmetic outcome. It is not just harm to the patient themselves which is troubling, dissatisfied patients with BDD have been known to threaten their treating medical practitioner both legally and physically. On rare occasion, the patient has even murdered their surgeon. Thus, BDD is generally considered to be a contraindication to cosmetic intervention.

Role of psychologists

There is a real need for psychologists to undertake research in this area. There is still much work to be done to identify the preoperative patient characteristics that are associated with poor outcomes, design psychological screening measures to assist with assessment of patient suitability, as well as investigate the impacts of cosmetic procedures on psychological wellbeing and quality of life.

In addition to research, psychologists can perform important clinical roles. Ideally, medical practitioners would always work together with mental health professionals to evaluate the suitability of their patients for cosmetic procedures. According to the 2016 Medical Board of Australia's Guidelines for registered medical practitioners who perform cosmetic medical and surgical procedures (p. 3): Patients can be quite secretive about any psychological issues, particularly BDD, out of concern that their procedure request may be declined. Medical practitioners may not always know what an "underlying psychological problem" looks like or know what questions to ask. This has meant that medical practitioners have performed procedures on patients in the past only to discover later that the patient had BDD, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

This suggests an important role for psychologists in the education of medical practitioners to assist them in identifying potential psychological issues in their patients. Like psychologists, medical practitioners are required to complete professional development activities and this could be a useful platform for psychologists to provide this information to medical practitioners in a simple and accessible format. From my own experience and speaking with other psychologists, it is important to be aware that some cosmetic medical practitioners may be wary of psychologists. It is also important to remember that we are all working towards the common goal of finding the treatment which will most benefit the patient, and this focus should assist health professionals to overcome hesitations about working together.

Assessment tools and limitations

Once the medical practitioner has identified the potential underlying psychological problem and made the referral to a psychologist, a thorough psychosocial assessment should be conducted. Individuals seeking cosmetic interventions may not be willing to consult with a psychologist for an issue which they may perceive to be purely physical in nature. It is important that patients be reassured that the discussion with the psychologist is also part of their treatment rather than the psychologist checking whether the patient is 'crazy' or not.

Unfortunately, there are currently a lack of psychometric measures to assess psychosocial risk factors in people seeking cosmetic procedures. There are certainly validated measures to screen for BDD, such as the Yale-Brown Obsessive – Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS), Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire (BDDQ), and the Cosmetic Procedure Screening Questionnaire (COPS). There is also a new wave of patient reported outcome measures being developed for specific procedures (e.g., BREAST-Q for breast surgery, FACE-Q for facial procedures) under the so called 'Q Portfolio' which examine pre-operative expectations for the surgery as well as outcomes. It will be interesting to follow the development of further scales in this Q Portfolio series.

Nevertheless, none of the current measures replace a comprehensive psychosocial assessment. In addition to a general history, this assessment should include; an exploration of the motivations, outcomes and expectations of the procedure; the history of the appearance dissatisfaction; level of support from loved ones for the procedure; mental health review and risk assessment. This will allow the psychologist to give the most accurate indication possible to the referring medical practitioner of the patient's suitability for the requested cosmetic procedure.

For further information, please consult the APS practice guide for the psychological evaluation of patients undergoing cosmetic procedures.

The author can be contacted at: [email protected]