Loneliness, defined as a subjective experience of social isolation, has been identified as the next public health epidemic of the 21st century. While the word ‘lonely’ is often used colloquially, it is often confused with objective or physical social isolation and an individual’s personal desire to be alone. Loneliness, however, is not equivalent to physical social isolation, nor is it synonymous with choosing to be alone. The term is more accurately used to explain feeling disconnected from others, and refers to a negative perception of one’s relationships (Peplau & Perlman, 1982). Loneliness is also related more to the quality of relationships than to the quantity. Hence, one could be surrounded by others but still feel lonely, and conversely, one could be alone, but not report the adverse feelings of loneliness.

All human beings are vulnerable to experiencing loneliness. Unmet social needs are akin to other human needs such as thirst and hunger. In this way, while loneliness can be a distressing feeling, it serves a function and is a signal to reach out to and to rely upon others. This reliance is critical, as it prevents us from having to depend solely on our own resources to survive, thrive or flourish. Feelings of loneliness, even if one is seemingly embedded within a rich social network, have been shown to be harmful for one’s physical and mental health.

Loneliness and its impact on health

There is evidence to suggest that loneliness is associated with a 26 per cent increased likelihood of mortality (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, 2015). Indeed, the links between loneliness and poor physical and mental health outcomes are now well established. Loneliness increases our risk of experiencing poorer health outcomes from decreased immunity, increased inflammatory response, elevated blood pressure, decreases in cognitive health, and faster progression of Alzheimer’s disease. It is no surprise that higher levels of loneliness are related to more severe mental health symptoms. While, loneliness is most commonly examined with depression, anxiety has been found to also play a role, with evidence from large population studies indicating that anxiety increases the odds of feeling lonely (Meltzer et al., 2013).

While the unpleasant nature of loneliness may motivate a ‘lonely’ individual to make attempts to connect with others, they are also more likely to be hypervigilant to social threats. This hypervigilance predisposes the lonely individual to seek and find evidence that people around them do not want to connect, or are less trustworthy. The hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis is a biological mechanism that responds to threats and has previously been shown to be activated more in lonely people compared with non-lonely people (Hawkley, Cole, Capitanio, Norman, & Cacioppo, 2012).

Furthermore, ‘lonely’ individuals show fewer prosocial behaviours towards others in an attempt to protect themselves from social rejection. This in turn increases the risk of being rejected by others, making them an active participant in a self-perpetuating cycle of loneliness. Hence, simply inviting a ‘lonely’ individual to join a group or interact with others provides either minimal or transient relief from loneliness, particularly once this has become a chronic experience or cycle.

Loneliness has been found to be ‘transmissible’ throughout social networks in the community (Cacioppo, Fowler, & Christakis, 2009). Specifically, those who are lonely are also likely to have friends who are lonely, and those friends are more likely to have friends who are lonely and so on; this demonstrates that loneliness can occur up to three degrees of separation from the lonely person. How loneliness is actually transmitted is unknown. One hypothesis is that if lonely individuals show more negative affect and rejecting behaviours, and are less cooperative with those around them, then this is likely to have a negative impact on those around them. What is known is that ‘lonely’ individuals also report fewer friendships or fewer social ties over time, suggesting that they may be more likely to either sever their ties or be predisposed to being rejected by others. These findings have implications for both the lonely individual and for those around the lonely individual, but it requires further investigation specifically into how the transmission process occurs.

Risk groups and risk factors

Although loneliness affects everyone in the community, studies have noted that young adults (18-29), together with older adults (65-79), are the most vulnerable, reporting the highest prevalence among age groups (Nicolaisen & Thorsen, 2014). This can be considered counterintuitive, as adolescents and young adults are often assumed to be embedded within well-established social structures. However, adolescence and young adulthood are also associated with significant social changes; from fitting into social groups and leaving school or home, to completing higher education or finding work. Adolescents and young adults are more reliant than ever on their social networks for support; consequently, experiencing a disruption in a small segment of their friendships, for example, can have a profound impact.

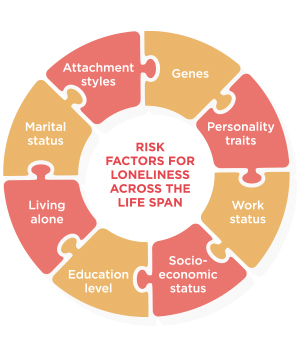

Different risk factors have been identified and these tend to differ across the lifespan. At present, it is unclear why some individuals experience loneliness as a transient feeling while others are trapped into a chronic cycle. Hence, solutions that are aimed at reducing loneliness should take into account the aspect of chronicity as well as different risk factors or barriers faced by the lonely individual. For example, individual differences, including personality traits, genes, and attachment styles, have been shown to contribute to higher levels of loneliness. Particular demographics such as marital status, living alone, work, educational and income levels, have all been identified to influence loneliness, depending on the study and sample. Loneliness appears seemingly simple to resolve but may not be easily addressed as it is likely a consequence of a multitude of factors. An example, is that some individuals may feel relief by having more social interactions while others may only experience relief once they overcome particular barriers, e.g., moving back home. Unfortunately for some, chronic loneliness persists regardless of increased social resources.

The increasing reliance on digital technology to communicate with others is one societal trend that is hard to ignore. Many are quick to blame the rise of technology and assume that it compromises face-to-face interaction. More recently, the term ‘Lonely Paradox’ has been used to describe how loneliness can persist even though we are more digitally connected than ever. However, research has yet to determine if this is indeed the case. Specifically, the uptake of technology has only significantly accelerated in the past five years, with more than 50 per cent of the population now carrying smartphone mobile technology (Poushter, 2016). It is difficult to assess the actual impact of technology on human communication, apart from examining anecdotal experiences. Notably, the ways in which technology is used are likely to make a difference to feelings of loneliness.

For example, young people who keep in touch with friends they made offline (e.g., at school) through online platforms are less likely to be lonely. Additionally, sub-communities of young people who meet online are also able to develop offline networks (e.g., gamers who attend conventions, thereby meeting online friends in offline settings). Further, as technology advances, it has the potential in the near future to serve as a vehicle for more ‘real world’, face-to-face style interactions. An example is the use of video-based tools (e.g., FaceTime) to communicate with family, friends, and colleagues. Over time, communication tools may even evolve to a point where social interactions can be facilitated with the use of augmented reality or the use of holograms.

Loneliness in clinical practice

Loneliness is often undetected, misidentified, or may be easily dismissed by trained mental health clinicians. There are multiple reasons why this is the case. Loneliness is not formally identified as a variable to consider within clinical training programs, nor is it a topic often discussed in the current public domain. Two plausible reasons for this lack of attention are outlined below.

First, loneliness is felt by everyone and hence, it can be assumed that these feelings dissipate once one interacts with another, which diminishes the perceived severity of its effects. Furthermore, loneliness can be triggered by commonly experienced life events, from transitions (e.g., starting a new school, workplace) to adverse circumstances (e.g., bereavement). Because we are all susceptible to feeling lonely through these common life experiences, it can be assumed that we should therefore all know how to manage these feelings. What is not often acknowledged is that the lonely person often faces multiple barriers. For instance, the lonely individual may not be embedded within a rich social environment that facilitates making meaningful connections, or they may not feel competent in initiating new ties.

Second, mental health clinicians may not readily be able to distinguish between loneliness and depression. Although loneliness is related to depression, they are distinct constructs. Loneliness is characterised by the negative perception of one’s relationships (e.g., their relationships are not meeting their needs), whereas depression relates to the negative perception of many aspects of life more generally. Without understanding the relationship, clinicians can easily mistake loneliness as depression and pathologise these feelings.

Identification and assessment

The term ‘loneliness’ has connotations of fragility and vulnerability, similar to terms such as depression and mental illness. Alternative terms can be used to refer to the absence of loneliness, such as strong, meaningful connections, or social connectedness. There is ongoing debate about the use of the term ‘loneliness’ and whether the word is negative enough to demand action within a public health campaign. Some argue that using the word itself will reduce the stigma of feeling lonely, while others advocate that positively-worded terms can prompt more proactive discussions amongst ‘lonely’ individuals and their community. This is because many ‘lonely’ individuals do not necessarily perceive themselves as ‘lonely’, though they may verbalise distress, dissatisfaction, and worry about their interpersonal relationships and functioning. Probing questions such as, “Do you ever feel like you are not in tune with others around you, or that you are not really speaking on the same level?” may be more helpful for clinicians who work with individuals who do not readily recognise their own loneliness. With those who are more open to expressing feelings of loneliness, clinicians can take the opportunity to acknowledge and normalise lonely feelings within the psychoeducation process. Clinicians can also use the gold-standard psychometrically validated self-report measure, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, to assess loneliness severity.

Interventions or solutions?

While loneliness is often examined within scientific literature, few studies have adopted a longitudinal design to understand what perpetuates loneliness. Consequently, there is a lack of crucial information that can be used to inform effective interventions. Notably, one study found that social anxiety plays a crucial role in predicting loneliness within a six-month period. This means that interventions and solutions aimed at reducing loneliness should identify and address co-occurring social anxiety symptoms; failing to do so is likely to result in minimal improvements in loneliness (Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur, & Gleeson, 2016).

Interventions that focus solely on providing more social opportunities to the ‘lonely’ individual have shown minimal benefits. This is because loneliness is not a simple equivalent to being alone or physically isolated, and is not even strongly correlated with time spent alone. This is problematic as many organisations that want to reduce loneliness develop and implement programs that solely focus on providing consumers with more social opportunities. Indeed, researchers have found that the most effective interventions offer a two-tier approach; addressing maladaptive cognition about others via cognitive-behavioural oriented interventions, in addition to offering social opportunities (Masi, Chen, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2011). Another promising approach that requires further evaluation is using a strengths-based, positive psychology framework, which is designed to increase the meaningfulness of existing relationships, promote positive emotions, and focus on thriving during times of adversity. Further research is required in understanding the impact of strengths-based interventions on mitigating loneliness.

Within a therapeutic setting, clinicians should assess for problematic levels of social anxiety symptoms, as not addressing these will prevent the individual’s ability to fully connect. The clinician can also focus on identifying and addressing maladaptive fixed beliefs about others and the greater social world. But it is important to consider the extent of the individual’s access to a rich social environment (e.g., living, work, social activities), as well as their feelings of social competency. Specifically, some individuals are further faced with physical barriers (e.g., lack of mobility, demanding work schedules, and comorbid illnesses). In these cases, focusing on quality rather than quantity is particularly crucial; a focus on building upon existing relationships, such as turning acquaintances into friends, may be more feasible than a focus on making new friends.

Future directions for Australia

The United Kingdom is currently leading the way in highlighting loneliness as a key public health priority, with the British Government appointing a loneliness minister in early 2018. A minister to address loneliness is justifiable as the portfolio is likely to span across different areas, from health, community, social, to the workplace. The UK’s ‘Campaign to End Loneliness’ (www.campaigntoendloneliness.org) which targets older adults, has been a successful endeavour, and has been used as a model for other countries pursuing the same agenda. More recently, the UK’s Royal College of General Practitioners has also developed a Community Action Plan on tackling loneliness at the primary care level, again highlighting the importance of loneliness and health.

Australia is following this lead. This year the Australian Government dedicated $46 million to the Community Visitors Scheme, a program that links volunteers with older adults who do not receive visitors in both community and residential settings. An additional $20 million has been assigned to older adults diagnosed with a mental health disorder and may be particularly vulnerable to experiencing loneliness. While these investments are a welcomed first step, the impact of these programs is unclear without proper evaluation. What is required is a more established understanding of loneliness and how it is experienced on an individual, community, and societal level. While loneliness has been consistently identified as a public health concern, loneliness is at risk of being belittled and its impact underestimated in Australia.

At present, there does not appear to be a ‘one size fits all’ solution for loneliness. We can, however, seek to develop ‘one size fits most’ solutions. Evidence-based solutions are not just informed by rigorous data but also designed, developed, and informed by the perspectives of consumers and the community around them. There is significant progress to be made in Australia; not only in loneliness being recognised as a serious public health issue but also in providing effective, evidence-based solutions. Despite these challenges, addressing loneliness in Australia will have a positive impact on ‘lonely’ individuals, community wellbeing, and the health system as a whole.

The author can be contacted at: [email protected]