We need to move beyond the stages and phases approach to grief support and instead support clients to navigate the series of ongoing waves that grief presents, says Dr Judith Murray, counselling psychologist.

Article summary

- Grief isn’t something to be ‘treated’ but rather a natural experience that psychologists need to help people learn to live with, says Dr Judith Murray, counselling psychologist.

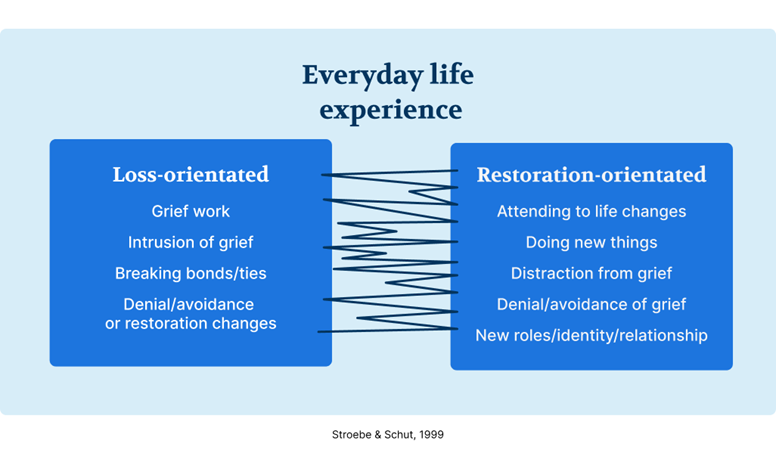

- Psychologists can refer to the Dual Process Model when supporting clients through grief, which outlines the oscillation between loss-oriented and restorative-oriented experiences.

- Studies show that grief is mainly experienced within the limbic system in our brains, which is our survival system.

- Grief requires a combination of top-down and bottom-up skills, as well as a broad integration of psychological frameworks.

- You can learn more from Dr Murray at the APS College of Counselling Psychologists Conference on 26-27 July in the Gold Coast. Register today.

Those who've experienced a deep loss in their lives, be that of a loved one, a relationship, or their health, for example, know that grief has an unsettling way of sneaking up on you.

One day, they might wake up feeling better. They're able to pull themselves out of bed, take a shower and drive themselves to work. Then a song comes on the radio that reminds them of what they've lost, and all of a sudden, they are overcome with emotion.

When they arrive at work, they might pull themselves together before walking into the building, only to crumble again when a colleague places a well-meaning hand on their shoulder and asks the inevitable question: "How are you doing?"

This is why traditional linear models of the stages of grief often don’t reflect the lived reality, says Dr Judith Murray, who is a counselling psychologist, a registered nurse and a secondary school teacher.

There's a misconception by some that grief is an illness that needs to be cured, when it's actually one of the most natural processes for a human to experience, she says.

Psychologists can help people think about grief as a healing process instead, says Dr Murray, who is presenting on the processes of grief and integrated care at APS's College of Counselling Psychologists Conference on 26-27 July.

"This is not just some glib advice to simply ‘change their thinking’," she says. "Rather we need to support people in how they see grief. It needs to come from a place of the deepest respect for both them and the process – and it takes time.

"I talk about grief as being experienced as waves. As a psychologist, you can use all your skills to help people deal with the waves, but you're not trying to stop the natural process of grieving. You want to help them calm down the waves that threaten to overwhelm them."

Your role as a psychologist is to guide that individual into and through uncertainty, she says, and help them "to feel safer out in the waves".

As a psychologist, you can use all your skills to help people deal with the waves, but you're not trying to stop the natural process of grieving.

Grief can't be 'fixed'

When training psychologists to manage grief, we often do so from a deficit model, says Dr Murray. We might consider it to be a disorder that needs to be ‘treated’. And, indeed, it often looks awful and feels awful.

"Think about diagnosis according to the DSM-5 or ICD-11. You get a diagnosis because you reach a certain level of symptomatology. So people either have a certain disorder like Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), for example, because they meet those criteria for their symptoms, or they don't.

"That's not the situation with grief. Everybody who grieves has symptoms, so how do you easily decide when it becomes a ‘disorder’? If we take a symptomatology approach – thinking of it as something we have to fix – we're essentially saying it's something that will go away over time if given the ‘correct’ treatment."

But fixing grief and returning to ‘normal’ doesn't happen, she says. Instead, people find the waves and their experience of them change over time, and they find space inside themselves to house that grief for the rest of their lives.

"Within that space is paradox – pain and love, weakness and strength, hope and fear, destruction and creation. Psychologists can be people who help those who grieve to find that space," says Dr Murray.

It’s also important to note that the stages and phrases of grief that many people have been taught is a misunderstanding.

"It suggested a definitive linear model from distress to acceptance – and that we'd 'get over it’. But that's not even what Elisabeth Kübler-Ross said, anyway. She was speaking about dying and loss of health. She just highlighted what looked like signposts among the real ‘messiness’ of the lived experience of dying and grieving."

See APS’s on-demand webinar, ‘What it all means at the end: Working with people making sense of the end of their lives’ for further information supporting people through the process of dying.

How grief works in the brain

Dr Murray believes that grief work is some of the most person-centred work you can do as a psychologist.

"Because what's going to work for one person, might not work for another person. Depending on what's happened, you might bring in trauma frameworks or there might be some attachment work that you integrate into your support approach.

"While many different psychological theories can beautifully complement each other in supporting someone experiencing grief, no single theory alone can provide a complete understanding."

Dr Murray finds it useful to explain simple elements of our neurobiological makeup to help people better understand how grief impacts us.

"Grief is felt right across the brain and through the body, but fMRI studies particularly show grief is [mainly] experienced within the limbic system in our brains," she says. "That's our survival system. It's where trauma lights up and it's where anxiety lights up."

The limbic system includes the amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and other structures that work together to process emotional responses, form memories and influence various autonomic functions necessary for survival.

"This part of the brain is essential for survival. It's responsible for perceived threats and attachment. I explain it to my clients as its core being both love and fear. My favourite quote about grief is from the great C.S. Lewis, who wrote, 'No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear,' and he was right."

Watch APS’s on-demand webinar about the forgotten mourners: how grief affects older people.

That fear can feel stuck inside people experiencing the waves of grief, so psychologists can have an impact by helping the flow of that energy around the brain, she says.

"You can use your bottom-up skills to do this: mindfulness, grounding, breathing exercises, etc. They don't have to be logical; people can use the power of the body to do it. Then you can use your top-down skills, such as CBT and language and problem solving, so clients can use the front part of their brain to help to get the necessary movement."

The movement that Dr Murray is referring to is an oscillation between two different aspects of grieving which are explained in the Dual-Process Model of Coping with Bereavement (see below), which is commonly used during grief work. The model recognises that there are both loss-oriented experiences and restoration-oriented experiences in our grieving."

"Clients will have moments where they feel stuck with the loss, pain and memories. In the early days of grief, they spend a lot of time there. But they still have to do all kinds of day-to-day things, like taking the kids to school or organising the funeral. So they have to spend time in that restoration mode.

"What the Dual Process Model says is most important is that a grieving person is able to oscillate between loss oriented and restoration stressors. If you stop oscillating, it argues that's when we get into trouble as you get ‘stuck’ in one side or the other.

"For example, people who get stuck in the loss-oriented side might end up with things like shrines – they just can't function easily in everyday life. This ‘stuckness’ is characterised in the new diagnosis in the DSM-5-TR for prolonged grief disorder.

"You can also get people stuck on the restoration side. They don't go anywhere near the grief, but we don't diagnose them as experiencing prolonged grief. We might see them experiencing alcohol and drug problems, or having relationship breakdowns, for example."

The movement between the two experiences allows for movement between the front part of the brain (the prefrontal areas) and the limbic system.

"This helps people to integrate their brains in dealing with their grief, move the energy around the brain and, over time, move their intense experience of grief into the larger story of their life within the autobiographical parts of the brain."

Explaining grief to clients

Psychologists do more than just provide steady, stable support for clients experiencing grief. They also play a crucial role in educating the community about the realities of grief, says Dr Murray.

She finds the metaphor of a broken leg to be useful.

"I say, 'We don't fix the broken leg. We put a cast around it to help with the amazing natural process of healing. We do, however, identify if there's an infection in that broken leg. In the natural process of healing in grief, we may need to help ‘clean out’ the things that may stop healing from occurring.”

Different psychological theories help psychologists determine if there's an 'infection', she adds.

"That might look like attachment work, where we would talk about problems of insecure attachment patterns prior to a death, for example. Or working with the traumatic events surrounding the loss. Or social constructionist ideas would talk about things like disenfranchised grief and problems in family patterns of grieving.

“Once we have been able to ‘clean out’ the infection by easing the complicated pain, the natural process of healing can begin or continue."

Hear more from Dr Judith Murray and a range of other psychologists at the APS College of Counselling Psychologists Conference on 26-27 July in the Gold Coast. Register today.