Research finds silver linings in a pandemic

We know from past research that positive outcomes and psychological changes can also occur amidst tragedies (Bonnano et al., 2010). A feeling of mutual community support is common in the immediate aftermath of a disaster and is linked to a sense of unity, solidarity, altruism and heroic action. Some people relate better to others or appreciate their life more after community-wide stressors or ‘mass traumas’. During the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, residents reported feeling more empathetic and more supported by loved ones, and prioritised their self-care and mental health (Lau et al., 2006). To look at this in the current context, we at the Black Dog Institute explored whether Australians had experienced any similar ‘silver linings’ during COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound health, economic and social consequences across the world. Beyond the direct impact of illness and loss of life, social distancing measures and lockdowns have put extraordinary demands on individuals, families, businesses and communities. The negative mental health impact of the pandemic has been widely documented. Research during the initial nationwide lockdown in Australia in 2020 revealed the negative short-term effects (Newby et al., 2020). Since then, unprecedented waitlists for psychological services and calls to crisis support services have risen rapidly, pointing to the longer-term impacts. Prolonged lockdowns in Melbourne and Sydney, and ongoing uncertainty across the nation, continue to take a toll.

Noticing the positives

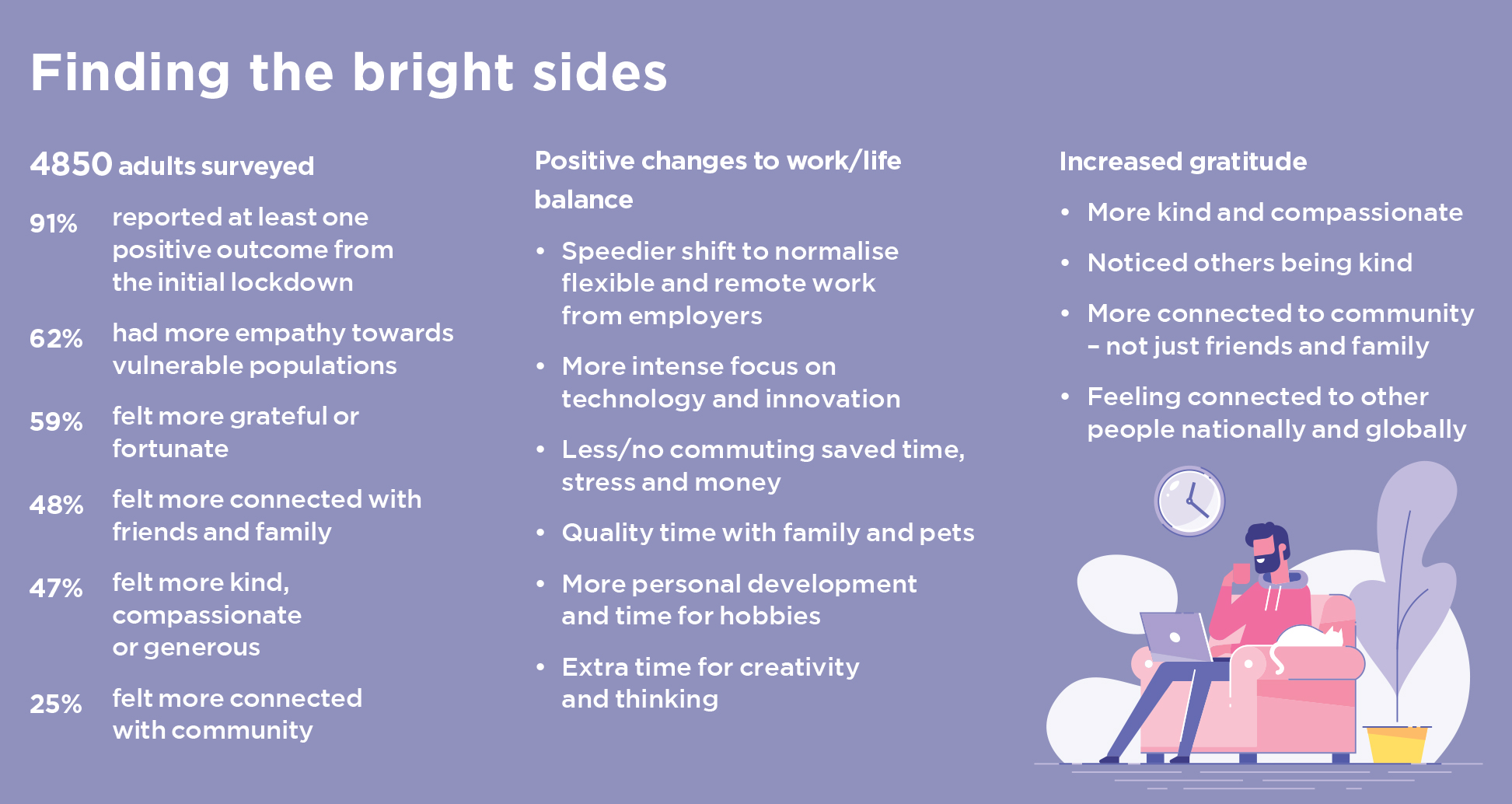

While acknowledging the significant pain of the pandemic, we wanted to explore whether Australians have also experienced any ‘upsides’ amidst the challenges. We surveyed 4850 adults from 27 March to 7 April 2020, during the initial nationwide lockdown, as part of a larger study on psychological responses to COVID-19 (Newby et al., 2020).

Participants were asked, Sometimes during difficult and challenging times, there can be positive experiences that come out of it. Have you experienced any of the following positives in the past week? They were shown five options, plus a free-text response box for ‘other’ positives. From the options, 62% of participants reported having more empathy towards vulnerable populations and 59% reported feeling more grateful or fortunate. About half the sample endorsed feeling more connected with friends and family (48%) and feeling more kind, compassionate or generous (47%). One quarter (25%) reported feeling more connected with their community.

One in four participants (23%) described a silver lining in the free-text response, which we coded for recurring themes. Some of these free-text responses expanded on the set options. For example, in addition to feeling more kind or compassionate themselves, people noticed others acting with more kindness: “Seeing people be more kind and compassionate towards others (e.g., neighbors checking in, people paying for other people’s groceries etc.) has lifted our spirits.”

Some people also described feeling more connected to colleagues, in addition to friends and family. Others noted a positive sense of community not just in their immediate community, but also at a national and global level: “The spirit of Australians and the world to get through this together.” Gratitude appeared in various ways, too, including more appreciation for simple things and existing work (e.g., “It made me very grateful for my work even though I struggle with it”), as well as more people expressing thanks to essential workers (“A stranger said thank you to me as I was walking to work in my uniform.”).

Finding common ground

The most common themes in the free-text responses were an increase in connection with others (12%) and having the opportunity to slow down (11%). One person reflected, “I felt a deep sense of relief having a break from the regular, busy lifestyle I lead.” Others talked about having more time for hobbies and connecting with their pets: “Not commuting and spending more time with my dogs is a plus.” Some people also spoke of how the extra time had provided more space for creativity to emerge (e.g., “feeling creative and like I have time to create and think”), or for personal development and learning (e.g., “Opportunities to learn new things (e.g., telehealth) and set new goals which I wouldn’t have otherwise”).

Another recurring theme was positive changes in the workplace and speeding up of innovations. For example, “Working from home was fast tracked. It wasn’t planned at my work for years to come.” Another person reflected that “We have been able to move forward in many things we have been trying to do for years and been beaten by bureaucracy and red tape and inertia.” Other people expressed greater optimism for societal changes, often related to systemic issues being unveiled, as reflected in comments such as, “Feeling more hopeful that real social change is possible now, and that the inequities are now seen more and will

be challenged.”

Interestingly, a small proportion of people (4% or 68 people) reported an improvement in their mental health and resilience. For example, “My self-compassion has grown during this time because working from home has given me the space to care for myself when I need it in that moment.” Fifteen participants (1%) also reported reduced stigma around mental health and feeling less isolated in their struggles. For example, “As people are experiencing feelings akin to anxiety and depression, some are becoming more sympathetic” and “I no longer feel alone. As someone who is isolated by the symptoms of severe PTSD, I now feel like everyone is in the same situation and that makes me feel kind of joyous!” This finding is consistent with impressions from our own clinical work and discussions with colleagues, that the lockdown had a validating impact for some people.

Overall, of the 4850 adults who participated, 91% reported at least one positive outcome from the initial lockdown, with half the participants identifying three or more silver linings. The increase in empathy, gratitude, generosity and sense of connection with others is consistent with the ‘compassionate stage’ that has been observed in the immediate aftermath of previous disasters (Bonnano et al., 2010).

Methods of coping

The findings also show that most respondents engaged in some form of meaning-focused coping, which may have helped their psychological resilience. In contrast to ‘problem-focused coping’, which involves attempts to change the situation (e.g., find new employment) and ‘emotion-focused coping’, which involves attempts to reduce distress (e.g., distraction), ‘meaning-focused coping’ refers to shifting beliefs and thinking in response to a stressor, and re-evaluating goals, priorities and values (Folman & Moskowitz, 2007).

Meaning-focused coping is particularly useful during prolonged stressors that are outside of an individual’s control. Negotiating a sense of purpose amidst suffering can help individuals meet their core psychological needs for autonomy and social connectedness (Jenkins et al., 2021). After 18 months of uncertainty, snap lockdowns, financial stress and separation from loved ones, meaning-focused coping may be more essential than ever.

Role for psychologists

Psychologists have a key role in helping individuals engage in meaning-focused coping. Therapy provides an ideal setting to validate a person’s suffering and help them to develop greater flexibility by reconsidering assumptions and values, to find a way forward. As one participant in our survey so eloquently put it, we can assist people to “[think] through what is really important, and what is not, to take forward from this rupture of past and future”. Psychologists can also encourage public messaging that instils hope and encourages prosocial action (e.g., working together to protect the most vulnerable within our community) to assist in prolonging the silver linings reported during the initial lockdown in Australia.

Our study provides a unique snapshot of Australians’ experience of lockdown. We acknowledge that using a convenience sample recruited online may limit the generalisability of the findings, particularly due to the overrepresentation of females. However, the high proportion (70%) of people who reported lived experience of a mental health diagnosis makes the findings even more relevant as we consider how to come alongside the most vulnerable in our classrooms, workplaces and therapy rooms: we must not lose sight of humans’ incredible capacity for resilience. May we continue to support one another in finding glimmers of hope in this challenging time.

Contact the first author: [email protected]