In recent years, too many organisations have faced public scrutiny over questionable workplace practices and the treatment of their workers. Amazon is the latest in a string of global businesses accused of unfair and unsafe working conditions, with suggestions of high work demands, considerable time pressures, unstable work arrangements, abusive supervision styles and excessive monitoring. Rapid advancements in technology, globalisation and consumer demands are some of the factors that have contributed to this and other prominent examples of work intensification. As psychologists, we should be concerned about the psychological health and wellbeing implications of such work practices.

A new employment landscape

The fast pace of change, globalisation, new technologies, desire for greater work control, automation and industrial shifts have seen developments in the types of work in which Australians are engaged. We have seen the emergence of the ‘gig economy’, characterised by short-term, temporary work engagements. Technology has facilitated this progression, providing platforms for the contracting of work, such as Uber and AirTasker. While this has been happening, sectors like retail have also transformed, and with the use of the internet so prevalent, consumer demand for online shopping experiences is reshaping the industry.

Recent technological advances are both helping and hindering our working lives. While technological change can often make work easier, it also has the potential to de-enrich job roles, decrease wages, and increase work intensity and demands. Nevertheless, technology can be used to improve working conditions through automation of mundane tasks, allowing humans to focus on more meaningful, stimulating and creative tasks.

As the global economy continues to change and we experience increasing technological disruption, the types of job opportunities available to Australians will continue to change. There is certainly much discussion about a growth in non-standard work (that is, forms of work that do not follow a permanent, full-time pattern) and the casualisation of the labour force. It is true that many people want casual working hours, but many large organisations are relying more heavily on a casual workforce, yet often the people they are recruiting ideally desire more permanent work arrangements.

Worker vulnerability and exploitation

Changes in the nature of work and the ways work is organised and performed has presented many challenges. While these changes may have increased control and flexibility in the labour market for some, they have also increased the risk of mass exploitation of other workers, particularly those that are young and born overseas (Howe, 2016; Patty, 2018; Ruiz, Bartlett & Moir, 2019). Self-employment, labour hire, casual work, fixed-term contracts and freelance work create an increased risk for vulnerability, exposure to poor work conditions and exploitative work arrangements. Though there is no hard-and-fast data to help us better understand these risks, we should remain alert to the mental health impacts associated with these non-standard, insecure forms of work.

“As Australians and psychologists, we should be very concerned about day-to-day work experiences for Australians, and organisations operating in an unethical, uncaring and unsafe way”

Organisations are increasingly seeking to transfer risk and responsibility and cut overhead costs by outsourcing employment to labour hire providers. This allows such organisations to employ workers, set rosters with minimal notice, and remove workers from rosters with no rationale provided and little (if any) consequence to the business.

Since establishing in Australia late in 2017, Amazon’s work practices in relation to their ‘fulfilment centres’ have been criticised for making unprecedented use of labour hire arrangements, with all but senior management roles and some corporate functions allegedly outsourced (Hatch, 2018). Using labour hire providers is a convenient way for organisations to potentially avoid direct, or ongoing responsibilities to their employees. For example, if they experience a sudden shift in the marketplace that results in a significant decrease in demands for goods or services, they can easily dismiss a large proportion of their workforce without consequence.

Employment through labour hire companies can result in negative outcomes for employees. For example, difficulty accessing entitlements and leave, lack of fair treatment, feelings of job insecurity, and excessive concerns about work performance. Some employees put in extreme effort to avoid potential shift cuts perceived as a ‘punishment’ for less than optimal performance. Tasks for these workers can also be menial, offering no skill development. Consequently, these workers may lack opportunities to acquire ‘on the job’ knowledge and skills that could improve their future employment prospects.

The use of labour hire is not the only challenge for Australian workers. Young workers are also vulnerable to unfair treatment and possible abuse, because young workers often lack the skill and confidence to raise issues at work for fear of negative consequences. McDonald’s was recently accused of over-reliance on teenage workers due to their lower cost, churning out workers as they approach an adult wage at 21 (Farrell & McDonald, 2018). The medical profession has also come under fire in recent times, with suggestions junior doctors are placed under immense pressure, expected to falsify work hours, and required to work to unsustainable rostering arrangements, resulting in exhaustion (Aubusson, 2019).

Organisations today are understandably looking for a competitive advantage. Amazon is a good example of business innovation, looking to create a certain customer experience that’s probably difficult to achieve. Whatever the line of business, the drive to deliver the fastest, most efficient services should not outweigh an employer’s duty of care for their workers. Business success is important, we don’t want businesses to fail, and we certainly want to see innovation. But this should not be at the expense of quality of life and the mental and physical health of workers.

Implications for health and wellbeing

Work matters for our psychological health and general wellbeing. Although employment can be outsourced, responsibility for fair work arrangements and work health and safety cannot. Work environments such as those created by Amazon are not healthy or even sustainable for the average worker. We should expect that most workers would burn out relatively quickly in these settings. This is due to physical and emotional exhaustion, partly from the nature of the work tasks themselves, and partly due to relational and cultural aspects of their work life. Working within an organisation that does not demonstrate care for its employees and appears to be primarily motivated by money and self-interest is not conducive to a positive employee experience. When employers demonstrate a callous attitude towards workers, and employees are made to feel like their efforts are never good enough, it creates a perfect recipe for disaster as far as the wellbeing of these workers is concerned.

Work-related stress is estimated to cost Australian businesses more than $10 billion a year in lost productivity and sick leave (Safe Work Australia, 2013). Employers need to recognise stress as a significant workplace health and safety issue, and commit to more positive action in promoting health and wellbeing. For the casualised labour force specifically, it should be recognised that job insecurity and inconsistent income can lead to significant financial pressures. The Australian Psychological Society’s own wellbeing research demonstrates money concerns are one of the leading stressors for Australians (Coghlan & Liang, 2015).

When workers are exposed to prolonged stress, significant pressure is put on the body both physically and psychologically. This can lead to a range of poor health outcomes, including mental health conditions, as well as headaches, fatigue, cardiovascular disease, immune deficiency, gastrointestinal disorders and musculoskeletal disorders. This is a preventable burden on Australia’s health system in general, and on our own psychology workforce.

With the number of suicides in Australia increasing, we need to look to the range of factors that may impact on mental health conditions and poor life circumstances. As Australians and psychologists, we should be very concerned about day-to-day work experiences for Australians, and organisations operating in an unethical, uncaring and unsafe way.

Psychologists driving better outcomes

Work plays a critical role in the development, expression and maintenance of our psychological health. This makes organisations ideally placed to improve and nurture employees’ health and wellbeing for the benefit of the individual, the organisation, and our broader community. Despite the acknowledged risks of labour hire practices to employees, to date only some Australian states have made moves to implement labour hire regulation schemes. It is recognised that we need to see improvements to worker treatment in some organisations and industries, particularly in the context of the changing nature of work. This presents an opportunity for psychologists to lend their expertise to help organisations cultivate psychologically healthy workplaces.

A psychologically healthy workplace is one that is conducive to optimal wellbeing, with high levels of engagement, commitment and satisfaction, employee growth, development and success, and high performance at the individual, team and organisational level. It is not just about ‘mental health at work’ but rather all job and environmental factors that contribute to positive employee experiences. Psychologically healthy workplaces foster the health and wellbeing of their employees while striving for high levels of organisational performance and productivity.

With stress a common experience in Australian workplaces, employers have a duty of care and a strategic business responsibility to mitigate risks to the psychological health of workers. This is not just about having a great ‘health and wellbeing’ strategy. It’s about everything an organisation does in relation to its people strategy. Employees may leave a job because of high stress, but they don’t necessarily choose to stay because of low stress – they stay because of the quality of the work environment, the support they are provided, meaningful work, great co-workers, opportunities for personal and professional growth, and fairness and justice. These protective factors can buffer against the sometimes demanding nature of our everyday work and the pressures of ongoing change.

Healthy workplaces in practice

Good work practices are not just about the things we do, but also the things we don’t do. The onus is on every employer to put effective systems in place to identify and manage risks to both the physical and psychological health of workers. This should include monitoring the health of workers, reviewing workplace conditions, and consulting with workers about health and safety matters. While many organisations purport to do the right thing in managing health and safety risks, they are often duplicitous in having implemented harmful work practices and inadvertently creating psychosocial hazards, which have far less obvious safety implications, but are nevertheless very dangerous.

For the health, safety, wellbeing, satisfaction and performance of workers, psychologists need to work with employers on the design of work and the work environment. Good work design practices will take several factors into consideration, including how tasks are to be undertaken, the duration, frequency and complexity of that work, the resources available to help complete the tasks, work systems, and importantly the physical, mental, and emotional capacity and needs of workers.

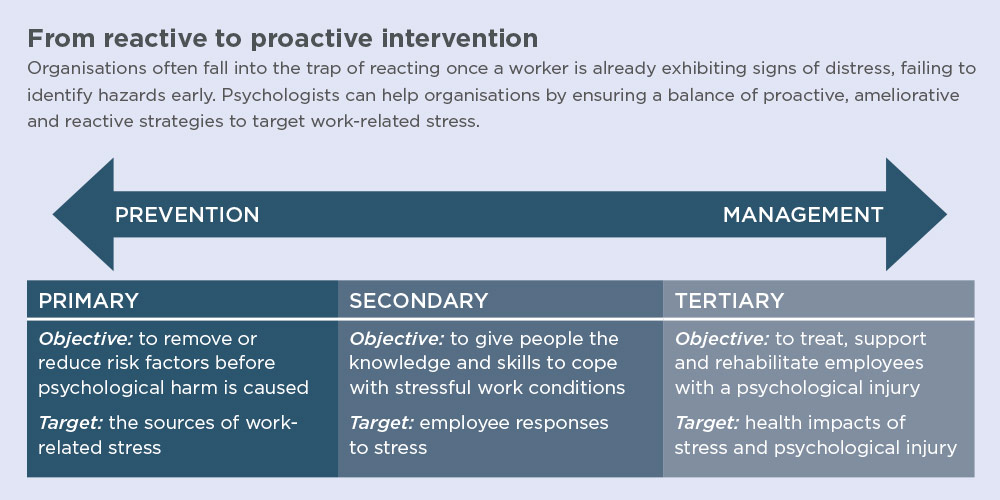

As psychologists, we can add immense value by using our expertise to understand the unique strengths, challenges and dynamics of each organisation, tailoring best-practice strategies to target root causes of stress, and foster a psychologically healthy environment.

The first author can be contacted at [email protected]