Suicide is the most common cause of death in Australians aged 15-44 years – more common than deaths from motor vehicle accidents or skin cancer (Aleman & Denys 2014). Over 2,500 people die from suicide in Australia each year and more than 65,000 make an attempt. Rates have fluctuated over the last two decades from causes unknown. Youth rates in Australia substantially reduced from the mid 1990s, but evidence suggests these rates may now be climbing. Australia’s youth suicide rate is higher relative to other similar OECD countries (VicHealth & CSIRO, 2015).

Policies and implementation

Over the last two decades or more, the Commonwealth and the States of Australia have developed suicide prevention policies to assist in lowering suicide rates. Australia’s national policy – The National Suicide Prevention Strategy (NSPS) provides the platform for Australia's national policy on suicide prevention with an emphasis on promotion, prevention and early intervention.

The strategy has four key components; the Living is for Everyone (LIFE) Framework, the National Suicide Prevention Strategy Action Framework, the National Suicide Prevention Program (NSPP), and mechanisms to promote alignment with and enhance State and Territory suicide prevention activities. New policies have been released regularly from the States over the last decade. Indeed in the last year or two new strategy documents have been released for NSW, NT, Western Australia and Victoria. The Elder's Report into Preventing Indigenous Self-Harm and Youth Suicide was published in 2014.

Suicide has been an important part of the National Mental Health Commission’s remit where it took on suicide as a goal in 2013 (see A Contributing Life: the 2014 Report Back on the 2012 and 2013 National Report Cards on Mental Health and Suicide Prevention). CRESP undertook a review of all suicide prevention policies for the Commission in 2013 and found much overlap and synergy across international, national and State policies, with key strategies such as reducing access to the means of suicide and appropriate reporting of suicide in the media being almost universally endorsed.

However, despite agreement about what should be done in suicide prevention, the implementation of suicide prevention policies has been less comprehensive. Indeed, there has been frustration about the piecemeal and uncoordinated effects of State and Federal actions. At the same time, evidence from Europe and Japan has been mounting that the best suicide prevention approach is likely to be gained from a multi-level, multifactorial systems based approach. One of the earliest examples of this approach is the Nuremburg Alliance against Depression (NAAD) which was a 2 year systems approach community program that combined four levels: co-operation with primary care, public relations campaign, community facilitators and high-risk groups and self help. The approach found significant reductions in suicidal acts (Hegerl et al., 2013). The success of the NAAD led to the development of a broader suicide prevention strategy across Europe and reductions in suicide attempts and deaths (Szekely et al., 2013).

There is growing support for taking this approach in Australia. CRESP reviewed the evidence for strategies with an evidence base and identified nine strategies that were likely to reduce deaths (see Figure 1). These included both community and public health interventions, but, additionally, health and medical interventions, such as care after a suicide attempt, psychological treatment and the proactive identification and management of depression by general practitioners.

Figure 1: Strategies likely to reduce deaths by suicide.

Although all these interventions are ‘evidence-based’, the impact of them relies just as much on the extent that identifications of coverage of the at-risk population is feasible and implementable as it relies on the the size of the effect. For instance, a highly effective strategy may have little impact if it can only be delivered to a small number of people. A relatively ineffective strategy which has the potential for huge roll-out can have high impact.

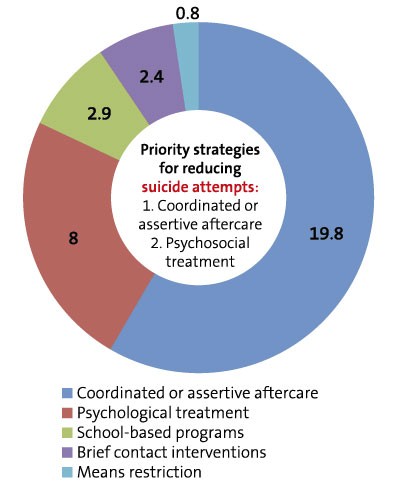

The extent that a strategy is effective can be estimated using population preventable fractions. For prevention of suicide deaths, it was found that the training of GPs, psychosocial treatment, and gatekeeper training were likely to yield the biggest effects. For suicide attempts, however, the strategies with the greatest impact were coordinated aftercare and psychosocial treatment (see Figure 2; Krysinska et al. 2015).

Figure 2: Priority strategies for reducing suicide attempts (Krysinska et al. 2015).

The extent to which suicide/ and suicide attempts are preventable can be calculated by adding the percentages. As can be seen in Figure 2, the fractions add to about 30%. This finding alone suggests that if suicide is to be prevented it requires input from a range of organisations, health professionals, community organisations, and from government, so that numbers can be reduced by this estimated amount. This organised systematic approach when all strategies are delivered in a geographical area has been termed the ‘systems approach’.

In November, 2015, The Paul Ramsay Foundation announced that it will fund a ‘systems approach’ to suicide in NSW, using four sites across rural and urban areas, and following the framework developed by the NSW Mental Health Commission. Black Dog Institute is excited to be the recipient of this donation of 14.7M and to be the agency with responsibility to implement a systems approach in NSW over the next five years. For more details about the Systems Approach Trial please visit the CRESP website.

A role for psychologists

Many professions will need to be involved in new ‘systems approaches’ to suicide, and it is likely that these will become the accepted framework for suicide prevention internationally as well as nationally. Psychosocial treatment is one of the strongest tools shown to impact suicide rates and to reduce suicide risk, so psychologists who deliver therapy are central to the approach. Cognitive behaviour therapy and dialectic behaviour therapy are

core, effective therapies for lowering suicide ideation in adults and young people (Ougrin et. al., 2015). Gatekeeping and coordination are also very important. Psychologists working in CentreLink, Lifeline, and other crisis intervention helplines, community health, school counselling, policing, youth mental health and many other settings have the opportunity to contribute to lowering suicide rates by identifying risk and coordinating care across multiple complex environments. The importance is clear of developing competency not only in risk assessment but also the skills for working collaboratively across disciplines (see CRESP website for information about training opportunities).

Future funding for suicide prevention

From the Commonwealth perspective, and despite considerable public pressure from clinicians, academics and the public, the Australian Government has not yet developed a formal National prevention plan. The recent announcement by the government to bring about mental health reform by empowering primary health networks to commission services and programs for suicide prevention and mental health was favourably received by the sector. However, as yet there is no guarantee that these newly consolidated and vastly diverse primary health care networks will preferentially fund evidence-based suicide prevention programs. Constraints, guidelines and accountabilities will be required. Moreover, the necessary funding for new initiatives in suicide prevention may take years to roll out. While we have agreement from the research evidence and the suicide prevention sector about the implementation strategy, what we need now is Federal Government support for the comprehensive implementation of these plans to commit to a national data-driven and scientific response to suicide prevention.