“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” - Martin Luther King Jr

VicHealth recently investigated the role of bystanders and racist incidents in its Choosing to Act report, conducted in partnership with the University of Melbourne and the Social Research Centre (Russell, Pennay, Webster & Paradies, 2013). A random sample of 601 Victorians were asked whether racism was acceptable in various scenarios in social settings, workplaces and sports clubs, what they would do if they witnessed racism in these scenarios and what they actually did the last time they witnessed a racist incident.Over the past 12 months, many Australians have seen aggressive racist attacks filmed by witnesses on their mobile phones. These incidents sparked a series of public debates about why some people intervened and others did not, and drew attention to the broader influence that bystanders have on racist cultures.

This study built upon an increasing volume of research that has demonstrated that racism can heighten people’s risk of developing some mental illnesses. Two studies recently released by VicHealth, the Lowitja Institute, the University of Melbourne, beyondblue and the Department of Immigration and Citizenship found that Victorian people from Aboriginal and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds who experienced the highest volumes of racism also recorded the most severe psychological distress, which placed them at higher risk than others of mental illnesses, such as anxiety and depression (Ferdinand, Paradies & Kelaher, 2013a; 2013b). This suggests that methods that short-circuit the accumulation of racist incidents could hold the key to preventing critical thresholds of psychological distress and some mental illnesses in these population groups.

The authors concluded that the individuals’ coping strategies did not seem to provide sufficient protection from harm, and that broader community and organisational efforts were required to stop racism from occurring in as many places as possible. Herein lies the important role of the bystander.

The Choosing to Act findings

One of the most striking findings was the overwhelming support (83%) for more to be done to address race-based discrimination. Approximately nine in 10 people believed workplaces and sporting clubs have an important leadership role through activities such as education, promoting cultures of respect and taking action when racist incidents occur.

The report also found that participants’ acceptance of racist incidents varied depending on what happened and where it occurred. For example, one-third of participants believed that racist jokes were never acceptable in social situations and 59 per cent thought they were never acceptable at work.

The participants were less accepting of racial slang and stereotypes (i.e., never acceptable for 60 per cent in social situations and for 78 per cent at work), with approximately nine out of 10 never accepting racist insults and sledges in any situation.

When asked if they were willing to take action against racism, 84 per cent claimed they would take action in at least one of the scenarios in each setting, with 30 per cent willing to act on every occasion. These patterns imply that people were less tolerant of racist comments directly targeted at a person compared to more generalised racist comments.

Perhaps the most interesting group were those who claimed they would feel uncomfortable if they witnessed racism, but would not do anything (ranging from 13 per cent to 34 per cent across scenarios). This group, of approximately one in four people across the sample, holds the potential for a new, powerful wave of action.

What bystanders did the last time they saw racism

Two hundred and five of the 601 participants witnessed a racist incident in the previous 12 months and 90 reported taking positive action. Nearly three-quarters of these people directly spoke to the perpetrator, 19 per cent spoke to somebody else (e.g., sought help or reported the incident) and five per cent physically expressed their disapproval (e.g., walked away).

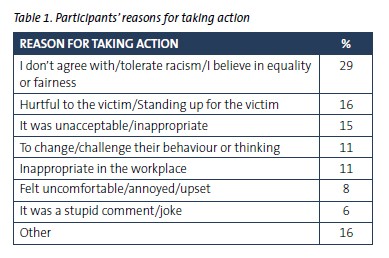

Table 1 shows that most participants were motivated to intervene by moral objections (e.g., “I believe in equality and fairness”) or to reduce harm (e.g., “It was hurtful to the victim”), whereas others sought to educate or change the perpetrator (e.g., “To change or challenge their behaviour”).

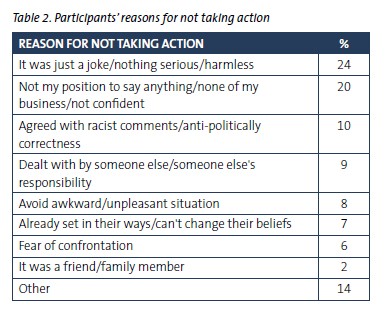

People who did not act considered that the act was harmless (e.g., “It was nothing serious”), that they had no role, authority or power to intervene (e.g., “It was not my position”; “I was not confident”), that the behaviours aligned with their morals (e.g., “I agreed with the racist statements”), that education would be futile (“They are already set in their ways”) or that they feared the repercussions of the confrontation (see Table 2).

What distinguished active bystanders from others?

The participants who acted after witnessing a racist incident were more likely than others to be concerned about race-based discrimination, supportive of cultural diversity and believe that that their actions could help. International researchers (Nelson et al., 2010) found that active bystanders were more likely than others to recognise race-based discrimination, understand the harm it caused, feel a responsibility to intervene, and feel confident to intervene. Bystanders were more likely to act in organisations and communities led by people who identified race-based discrimination, supported strong sanctions against racist practices and provided opportunities for positive inter-group interaction.

VicHealth’s Choosing To Act research concluded that survey participants were most likely to take bystander action if they were supported by their organisations, their peers and colleagues. Active bystanders were also more confident that racist behaviour would be taken seriously in their organisation (e.g., aware of policies; culture welcomed all people and encouraged everyone to take up important roles).

People were also more willing to take action against race-based discrimination in junior sports clubs compared with adult sports clubs and were more inclined to take action in larger (200 or more employees) than smaller workplaces. Those in larger workplaces also were more likely than participants in smaller workplaces to:

- Feel that racist behaviours were unacceptable (69% compared with 43%)

- Be aware of relevant workplace policies (70% compared with 41%).

Building the momentum of cultural change

These findings provide interesting insights into the steps required to encourage more people to intervene. For example, more work may be needed to explain the serious health consequences of racism, the impact of chronic exposure and the multiple channels of racist attacks. Aside from direct attacks, other racist acts that exclude or generate bias against people of certain races, religions or cultures can also contribute to harmful consequences (e.g., job selection, social alienation), particularly if they are repeated many times. Racist jokes, comments and stereotypes can undermine, degrade, humiliate or demonise people from certain backgrounds by exaggerating the threat they pose to others and eroding public sympathy or support. These conditions can create a fertile environment for subsequent racist acts to flourish.

More racism can be reduced or eradicated from Australian venues over time if people who feel uncomfortable when they see racism can be encouraged to take action when it matters. The metaphor of lifesaving demonstrates that bystanders do not have to put themselves at risk to make a difference. Most people would attempt to help someone who was drowning, even if they were not a confident swimmer. Bystanders can call for help, support other rescuers or assist the victim after the event.

Indeed, the violent racist incidents on public transport represent the more extreme edge of the spectrum of racism. It is much more common to witness incidents such as racist jokes, a racist posting on social media or someone being treated differently in a shop because of their race.

VicHealth has commenced a partnership with the Football Federation of Victoria to trial a new program to support bystanders in football clubs across Victoria. This will involve exploring structural changes such as policies and complaints procedures, as well as bolstering cultural change through promotions, training and leadership. The trial will be designed so that other sports can implement a similar program.

For more on VicHealth’s other anti-racism research and work in the arts, local communities and workplaces please see www.vichealth.vic.gov.au