Common features of cognition and temperament associated with both creative potential and psychotic disorders have been well researched, but alongside these identified similarities there has been little analysis of the differences between highly creative individuals and those with psychotic disorders. This article reviews evidence from experimental psychology and epidemiology, from which we propose a spectrum model of shared vulnerability to creativity and psychosis. This model offers fresh insights for both cognitive enhancement and remediation in young people at risk of developing psychotic disorders.

What is creative cognition?

Creativity involves the ability to generate new and original ideas that have value in a particular context (Torrance, 1993). Experimental psychology has shown that creativity can be measured by cognitive processes such as divergent thinking, abnormal pre-attentive filtering, and reduced latent inhibition (see definitions below). These cognitive capacities facilitate rapid and fluid integration of information in a way that can be explored and developed to form original ideas.

Divergent thinking

Divergent thinking describes a loosening of boundaries between concepts that facilitates the generation of multiple, uncommon and original ideas. People who show increased divergent thinking skills can often easily develop and elaborate ideas with details, and are good at processing information for use in alternative ways (Torrance, 1990). Within schizophrenia-prone individuals, there is substantial evidence of greater divergent thinking capacities (Green & Williams, 1999), and these have also been associated with particular personality traits in psychosis-prone individuals (Claridge & Blakey, 2009).

‘Defective’ pre-attentive filtering

Another cognitive feature common to creativity and psychosis proneness involves aberrant filtering (inhibitory) mechanisms operating below conscious (voluntary) awareness (Beech et al., 1989). Reduced filtering facilitates an increased flow of information into preconscious awareness that can result in an individual being inundated with simultaneous arrays of thoughts and idea fragments, with 'loose' associative links. Indeed, it has been proposed that reduced cognitive inhibition may form the basis of creative thinking, by providing the individual with a larger sample of ideas.

Reduced latent inhibition (LI)

Reduced latent inhibition has similar effects on the capacity to ignore the constant stream of incoming stimuli. It specifically affects the capacity to ignore information that has been previously learned to be significant in some way: a familiar stimulus takes longer to acquire new meaning (as an irrelevant signal in later trials) than a new stimulus that has previously had no relevance. Both individuals with high creative achievement and psychosis have been associated with low latent inhibition (Carson, Peterson, & Higgins, 2003).

Creative cognition and temperament along the psychosis spectrum

Along with creative cognition, features of temperament that are associated with creativity are often also associated with psychosis proneness. Common features of temperament include tendencies toward increased openness to experience and higher neuroticism, alongside decreased conscientiousness (Rybakowski et al., 2008). Specific features of schizotypy – unusual experiences and impulsive non-conformity – have also shown direct association with creativity in bipolar disorder (Rybakowski & Klonowska, 2011). Interestingly, Claridge and Blakey (2009) showed that affective temperament features were more effective in predicting creative potential than schizotypal features. Current evidence thus favours more common temperament features between creativity and bipolar disorder (that diminish toward the schizophrenia-end of the spectrum). This could be taken to suggest that expansive mood is good for creative thinking. Similarly, ‘affective’ temperament features such as the capacity to access intense and often negative and varied shifts in emotion, may promote cognitive flexibility (Strong et al., 2007).

Spectrum model of shared vulnerability

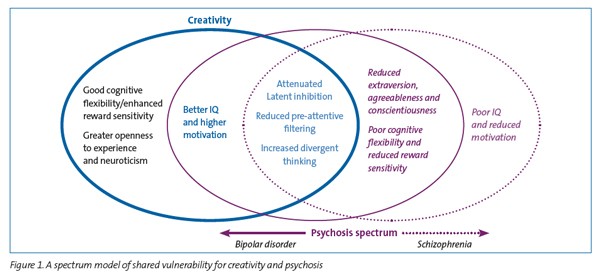

It appears that the very vulnerability to these psychotic and mood disorders is associated with a tendency toward creative endeavour that may be inherent in the shared genetic predisposition, evident in cognitive and personality features. However, the expression of this potential may be more commonly realised in bipolar disorder, while potentially stifled by other disturbed cognitive mechanisms in full-blown schizophrenia.

Epidemiological research also supports this notion. A large epidemiological investigation of the professional occupations of families with a history of severe mood and psychotic disorders found a significant over-representation of creative professions among individuals with bipolar disorder and the unaffected siblings of people with both schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (Kyaga et al., 2011). However, individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia did not have an increased rate of overall creative professions in the same familial group. The severity of the cognitive deficits in this most extreme version of psychotic disorder (schizophrenia) may thus impede creative expression.

For example, Carson (2011) suggests that highly creative individuals have ‘protective factors’ which allow creative cognitive potential to be translated to creative endeavour. Specifically, high IQ and cognitive flexibility are proposed as protective features of highly creative individuals that are not shared by mentally ill people (who appear not to be able to achieve the same level of creative potential). These features allow the creative individual to harness information for use creatively, rather than be overwhelmed by bizarre thoughts. However, a limitation of Carson’s model is that it does not differentiate among psychopathologies such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, whose temperamental features and cognitive profiles differ substantially, both within and between these diagnostic groups.

We therefore propose a spectrum model of shared vulnerability (See Figure 1), where differences among creative and non-creative individuals on the psychosis spectrum will reflect reduced cognitive flexibility and reward sensitivity (i.e., goal directed behaviour), alongside less extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness in psychosis-prone individuals, compared to highly creative individuals. Our model also distinguishes the usually ‘extraverted’ bipolar disorder individuals from the more introverted schizophrenia ones. In addition, our model highlights the role of frontal executive deficits that potentially impede effective management of the large amount of information made available by early pre-attentive filtering deficits in creative and psychosis-prone individuals alike. Furthermore, there may be qualitative differences between executive processes engaged during the creative process, which may be reliant on other cognitive efficiencies (e.g., greater working memory capacity; IQ) requiring advanced increased prefrontal control alongside the facilitatory features of temperament and cognitive aberrations that afford an increased array of incoming information.

Clinical applications of the spectrum model of shared vulnerability

Factors implicated as common to creative potential and psychosis vulnerability include enhanced divergent thinking, defective pre-attentive filtering mechanisms and reduced latent inhibition. On the other hand, greater cognitive flexibility, motivation and openness to experience tend to be associated with creative achievement, but not psychosis. The spectrum model of shared vulnerability enables exploration of this differentiation and can provide screening and interventions for adolescents at risk of psychosis.

Insights from the spectrum model of shared vulnerability can be used in the following clinical applications:

- Early identification and screening for young psychosis-prone individuals.

- Psychoeducation and resilience training for developing creative artists, aimed at providing an understanding of their shared vulnerability and associated mental health risks, and encouraging skills such as mindfulness training in an attempt to exert control over increased divergent thinking.

- The development of individual and group early intervention programs specifically to train in cognitive flexibility, and awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of (creative) cognitive and temperamental features, in order to self-manage overwhelming sensory (and irrelevant) information in psychosis-prone individuals.

- The differential application of creative programs for individuals with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, targeting their temperament vulnerabilities that may impede creative achievement.

Conclusion

Shared propensity for psychosis and creative thinking suggests that these aspects of cognition (and temperament) might be recognised as an ‘adaptive’ intermediate phenotype for psychosis. This understanding may facilitate clinical programs to enhance creative cognition and actualisation of creative potential in high-risk populations, potentially leading to increased vocational opportunity. These programs could successfully augment current psychoeducation and pharmacological management of the cognitive features of psychosis.

Acknowledgement

Melissa Green was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Institute of Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIAS) during the preparation of this article.

The first author can be contacted at [email protected]