Our current economic environment places increasing pressure on organisations to do more with less – to improve efficiencies, employee productivity and profitability with fewer resources. One consequence is a greater need to use valid recruitment methods to make correct selection decisions. Yet many organisations continue to use selection methods with little psychometric merit or legal defensibility. We would like to share our journey through the introduction and implementation of valid selection assessment tools in a not-for-profit, private healthcare organisation (4,000 employees across five hospitals and a corporate office, with a total of 180 managers) over an 18-month period.

Previous recruitment approach

Two years ago, the selection processes of the organisation involved selecting some interview questions from the intranet, conducting an unstructured, traditional interview using two interviewers, with ad hoc use of reference checking and work samples. Issues identified with this approach were: variable candidate experiences, even for candidates applying for the same role; lack of data to support ‘successful’ and ‘unsuccessful’ decisions; difficulty providing feedback to managers and candidates; no use of selection data to support them in their new role (‘onboarding’); higher number of clinical education hours for poorly performing graduates compared to their well performing counterparts; and performance issues with a significant proportion of selected candidates during or immediately after the probation period.

New selection strategies

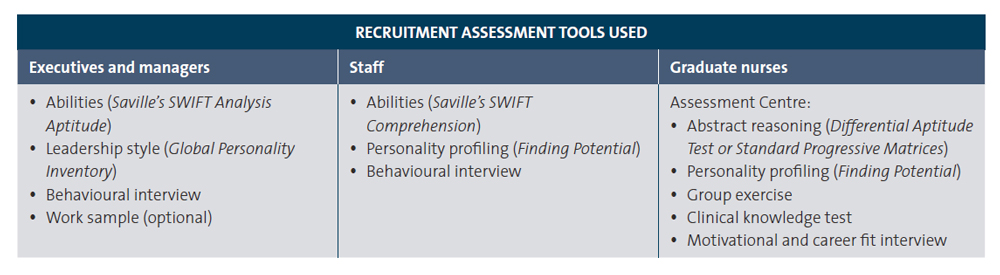

In the first instance behavioural interviews were designed, with questions aimed at eliciting specific behavioural capabilities, motivations and career fit, and corresponding scoring criteria. However, using these interviews alone did not give sufficient information for effective selection decision making, particularly in areas that are not amenable to training, such as cognitive ability and attitude. Psychometric assessment was introduced for recruitment to management roles involving verbal, numerical and abstract reasoning and a self-report leadership style/personality questionnaire, the Global Personality Inventory. This assessment tool identifies key leadership attributes such as leadership style, motivation, interpersonal style and resilience, but also includes potential leadership ‘derailers’ such as egocentric, intimidating, manipulative, micromanaging and passive aggressive tendencies. For some critical roles, group exercises and/or role plays were also added to the selection process. To maximise credibility, an external provider administered the psychometric assessment for management candidates. To manage costs, two internal psychologists provided debriefing on the results of psychometric profiling to managers and candidates.

Once good selection outcomes were realised for management candidates, managers started requesting that personality testing also be used for their staff recruitment processes. Given the limited budget of a not-for-profit organisation, a free online personality inventory (based on the Big Five personality theory) provided by Finding Potential was used for staff and graduate applicants.

Use of assessment centres

Further efficiencies have been achieved with the introduction of assessment centres to undertake graduate registered nurse recruitment. Bulk recruitment processes that previously involved up to eight weeks of interviews and reference checks have now been reduced to two to three weeks. This has been achieved through short listing using online applications, including personality profiling and conceptual reasoning, and then one week of assessment centre activities to select candidates and make offers. The cost of recruiting graduates has been reduced by more than 60 per cent using this methodology (32 candidates assessed per day). Assessment Centre data are used to place and onboard graduates during their rotations and identify where additional support might be needed to ensure their success. Written evaluations from candidates confirmed they believed the assessors clearly explained the process and what was expected, and they had a fair and reasonable chance to demonstrate their skills throughout the Graduate Selection Day.

Challenges and learnings

The first challenge was influencing the Human Resources (HR) team to become ‘champions’ for the new recruitment processes. They were initially concerned managers would perceive the use of these tools negatively and were not keen to promote the benefits of evidence-based selection practices. At first sight the interviews guides appeared much longer due to the behavioural criteria and scoring grids. Even though poor selection decisions had previously resulted in difficulties, it was necessary to reassure managers that it was worth following what might be seen as a more laborious process in the short term in order to get the best outcome. Some managers were cautious about including psychometric assessment due to a fear of ‘psychoanalysing’ candidates or as the result of previous negative experiences themselves as candidates. For selection processes involving group exercises or role plays, managers were concerned candidates may not be willing to participate or may become overwhelmed. The tipping point came during training sessions when managers realised that reference checks would no longer be required as long as two valid selection tools and verification of employment history were used (apparently reference checking had been a very unpopular part of the previous process). The new process was then seen as more efficient and more interesting.

Nevertheless, at times managers still become very enamoured with particular candidates and will appoint them, even when selection tools have flagged potential issues. Where this has indeed played out, emerging performance, attitude or interpersonal issues have been a crucial factor, with hindsight, in convincing recruiting managers of the value of using the new tools and processes.

Early adopters and champions of the new tools and processes were identified. One hospital adopted the new recruitment methods more quickly than other sites because of the proactive encouragement by HR professionals, showing the benefit of HR involvement and support from an early stage. Use of the recruitment tools was not made mandatory, but word of mouth spread far more quickly than envisaged, and within 18 months of introduction uptake of psychometric assessments had increased from zero to approximately 49 managers (27%).

In-depth training in behavioural interviewing, behavioural assessment and psychometric assessment was required for HR and managers. As psychometric testing became more popular it became difficult to ensure sufficient funds to sustain the use of external providers, although it was clearly identified that the internal team could not continue to support the demand. Internal staff in HR and clinical education required additional training and accreditation in these selection tools so they could support and upskill managers.

Achievements and benefits

Seventy-five managers (45%) have completed training in using the new tools and have moved to assessing individual applicants through behavioural interviews, ability testing and personality profiling, especially for executive and management roles. Being a values-based organisation, the candidate fit to the values and culture of the organisation is very important. Personality testing has been regarded very favourably in giving additional data when there has been a query about a person’s style or their potential fit with a team.

While it is too soon to report data on improvements in engagement, productivity and retention, anecdotal feedback from recruiting managers and HR suggests employees that have been selected using valid tools learn their new role quickly and fit in well with the team. What is harder to track is the number of ‘near misses’, where an unsuitable candidate did not progress due to a lower cognitive ability, or lack of fit in leadership or personality style with the team/organisation.

Feedback from both successful and unsuccessful candidates has been very positive. They commonly express their appreciation for the thoroughness and professionalism of the process. Frequently in healthcare settings candidates have completed placements or are already employed on a casual basis at a hospital. If they are unsuccessful for a permanent role this can potentially cause conflict within their work area and/or with HR. Having comprehensive, objective data to provide at the feedback session has meant there have been no escalations of complaints or legal issues over appointments to date.

| CANDIDATE FEEDBACK |

|

“Overall, it was a very well run process and provided me with an opportunity to display my skills and knowledge.”

“Really good way to interview - really fair!”

|

| MANAGER FEEDBACK |

|

“<<name>> is brilliant with patients and staff think she is wonderful, so enthusiastic, knowledgeable, wanting to learn and very caring with the patients.”

“<<name>> is an excellent graduate nurse. She has consistently been a high performer, especially as she is in a specialist area. We also have had other excellent grads but she has picked things up really quickly.”

|

Conclusions

It is early days in our journey, and we will track the results over the next few years to confirm the initial benefits we have identified. Anecdotal feedback from managers and educators suggests people who have been selected using valid assessment tools tend to get up to speed more quickly and assimilate into the organisation effectively. Only time will tell if fewer performance issues are experienced and if there is more potential for internal succession of new recruits who have been selected using valid tools and processes.

The principal author can be contacted at [email protected]