Your police career is like pushing a wheel barrow. Every job puts some sand in it. It gets heavier, but you get stronger and you can keep pushing it. Every now and then, a big job will put a large amount in and you will have to put the wheel barrow down for a rest and regather your strength. It can only hold so much, and if you don’t unload it in the proper way you may drop it when you hit rough terrain and spill it out everywhere. - Queensland Police Service member

Police have a specialised role within our community and function within an ever-changing local, national and international environment. Responding to community needs, policing involves a stressful work environment and intensive workloads including shift work, and carries a corresponding high risk of both physical and psychological injury. To respond to these risks, the Queensland Police Service (QPS) has a substantial internal Employee Assistance Service (EAS). With an established knowledge and familiarity of structures, processes, roles and cultures, the EAS provides different levels of customised interventions to maintain and enhance psychological wellbeing within a diverse and dynamic organisational environment.

The Employee Assistance Service

The EAS is comprised of specialised practitioners (psychologists and social workers) providing internal counselling services to members and organisational consultancy to managers and teams. The objective is to enhance employee wellbeing and reduce the risk of psychological harm in the workplace. The EAS has operated since 1990, ensuring opportunities to build and develop stable and strategic relationships with a range of stakeholders – the organisation, unions and its 15,000 employees. Networking and forming alliances with stakeholders is an integral part of maintaining psychological wellbeing. Every-day conversations foster a sense of trust and build rapport. This is a valuable currency to address any issues that arise, as practitioner and EAS professional reputation goes a long way to cut through the inherent discomfort and scepticism associated with providing interventions at the operational level within the policing culture.

Practitioners who work within EAS are geographically located throughout Queensland in every region, as well as in specialised commands and the training Academy. The range of different services offered includes: individual crisis and short-term clinical intervention; triage into external referral (if warranted); education and training; emergency after hours (on-call) service; psychological first aid after a critical incident; risk management of psychological injury and risk assessments for self-harm; screening and assessments; and management of the Peer Support Officer Network. Practitioners also offer an organisational psychology consultancy service to supervisors and managers, providing advice on: workplace dynamics; organisational wellbeing; supportive leadership and conflict management practices; and stress management and other mental health issues. Collaboration with other internal services, such as Injury Management regarding psychological injury, offers a ‘whole of service’ strategy to address psychological wellbeing in the workplace.

Promotion of psychological wellbeing

Psychological resilience is part of police recruits’ training at the Academy. Psychological literacy is developed and reinforced throughout their career, and multiple opportunities and methods are utilised to maintain focus on their psychological wellbeing. In 2013, the EAS had approximately 9,000 contacts with members, demonstrating that assistance is accessible and responsive. Employee Wellbeing services are promoted via computer screen savers, internal websites, brochures, posters, Peer Support Officers, and personal interactions with staff.

Face-to-face awareness sessions as well as education and training workshops are typical interventions designed to target the most common presenting issues of stress, depression and anxiety, relationships and critical incidents. Events such as Mental Health Week and National Psychology Week are also utilised as vehicles to promote psychological wellbeing and link with a wider mental health focus. Retirement preparation seminars have also been successfully trialled.

Providing police members with a multi-faceted approach to psychological wellbeing, the EAS also includes a team of chaplains and approximately 660 Peer Support Officers (PSOs) across the State. PSOs volunteer their time to assist and support colleagues experiencing personal and work-related difficulties and are generally the first point of contact. Although peer support does not replace professional counselling, the PSOs possess an understanding of local dynamics and can offer a valued peer perspective. PSOs are either police or staff members who are carefully selected and trained, and are required to adhere to a Code of Ethics which includes maintaining confidentiality except in cases involving duty of care or legal requirements. PSOs also provide practical support and assistance following critical incidents.

Management of critical incidents

On average, Australian police officers will experience nine critical incidents in a 12-month period (Hodgins, Creamer, & Bell, 2001). Within QPS, a critical incident is defined as “when a member through the course of their duty has direct personal experience of a threatened death, serious injury or other threat to their physical integrity; or witnessed an event that involves death, serious injury or threat to the physical integrity of another member of the Service”. A QPS study found that 95 per cent of participants experienced a work-related traumatic incident at some time in their career (Rallings, 2000). Of this number, a small group is likely to develop a mental health problem including substance use disorders, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The study identified that PTSD prevalence in the service is approximately eight per cent following work-related incidents. Recent evidence suggests a significant portion of this may in fact be misdiagnosed burnout (Gilmartin, 2014). Anecdotal evidence supports this theory, as members have reported a significant reduction in symptomology when placed into a different policing role.

In 2008, QPS partnered with the Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health (ACPMH) to facilitate the formal introduction of psychological first aid (PFA) within the service. PFA is a practical, individualised approach to managing a critical incident response. Professor David Forbes FAPS and other personnel from ACPMH worked with QPS to develop specific evidence-based and best-practice policy and procedures. The implementation and successful roll-out of PFA included a communications and education strategy that involved training presentations, policy development, internal marketing and supporting manuals.

Given the scale of the organisational shift and the need to educate 15,000 staff members and police officers about protecting psychological health, an online learning program was identified as a sustainable, cost-effective and efficient delivery method to provide knowledge and skills to ensure all members receive the appropriate level of support after a critical incident. The Psychological First Aid Online Learning Program won the Gold Award for Excellence in Corporate and Support Services at the QPS Awards for Excellence in 2012.

Challenges within the service

The size of the geographical areas that EAS practitioners are required to provide services in – some larger than the State of Victoria – are one of many challenges in the provision of psychological services. With the tyranny of distance (sometimes covering 2,000kms), practitioner creativity and flexibility in meeting the needs of members is fostered. Telephone counselling and use of video conferencing ensures that direct contact is possible when travel is not an option.

Due to the dynamics experienced in small towns, police are averse to utilising local psychological services due to perceived judgement and stigma in these communities. In areas where there are no external providers, the EAS practitioner may also support a partner or family member in a similar manner as an individual client.

Any internal EAS faces potential issues around dual relationships (management and employees) and confidentiality. In addition, police may be sceptical about utilising the internal service for fear of stigma or negative impact on their career. To highlight the credibility of the service, it has been important to educate members about the EAS, including the limits to confidentiality (for example, safety of clients and others, or serious misconduct) and the integrity of clinical records. Client files are kept separate from human resource records and are maintained in a secure custom IT section.

With regard to ethical practice and obligations to the organisation and to individual clients, it has been useful to have assistance from APS representatives, including Mr David Stokes FAPS from the National Office and Queensland Branch Chair Dr Michael John MAPS, to facilitate discussion and adherence to ethical principles in an ongoing complex role. Structured discussions have also included key organisational stakeholders from management, legal and ethical standards areas within QPS.

Benefits of an internal service

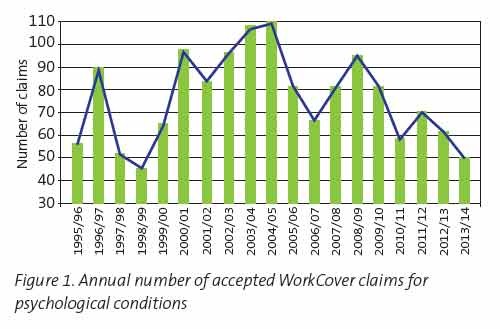

The internal nature of the Employee Assistance Service offers a number of measureable benefits to the organisation. These include cost savings in the form of reduced WorkCover premiums as well as a decreased number of WorkCover claims for psychological conditions. Data from the past 19 years demonstrates this important outcome (see Figure 1), and this downward trend has occurred despite the QPS workforce almost doubling in size for the same period. Since the introduction of the internal Employee Assistance Service, QPS records show a significant reduction in suicide rates among QPS members, with the rate currently at half the rate of suicide within Queensland’s general population (AISRAP, 2013).

Future directions

The EAS will continue to function utilising psychological research and technological developments in the context of an evolving organisational structure and environment, including destigmatising mental health and improving help-seeking behaviour. There is an added emphasis on organisational development strategies to promote employee wellbeing and utilisation of the EAS. Significant effort will be invested in the future to educating members and building capability in supervisors and senior managers to identify and support members with mental health issues. The focus will also be on improving the uptake of interventions such as Manager Assist, leadership and coaching programs, fatigue management, resilience training and mental health first aid. With a commitment to continuous improvement and a value-adding service delivery model, the EAS will ensure that the psychological wellbeing of Queensland police officers remains paramount.

The principal author can be contacted at [email protected]