The role of psychologists in the world of cosmetic medicine

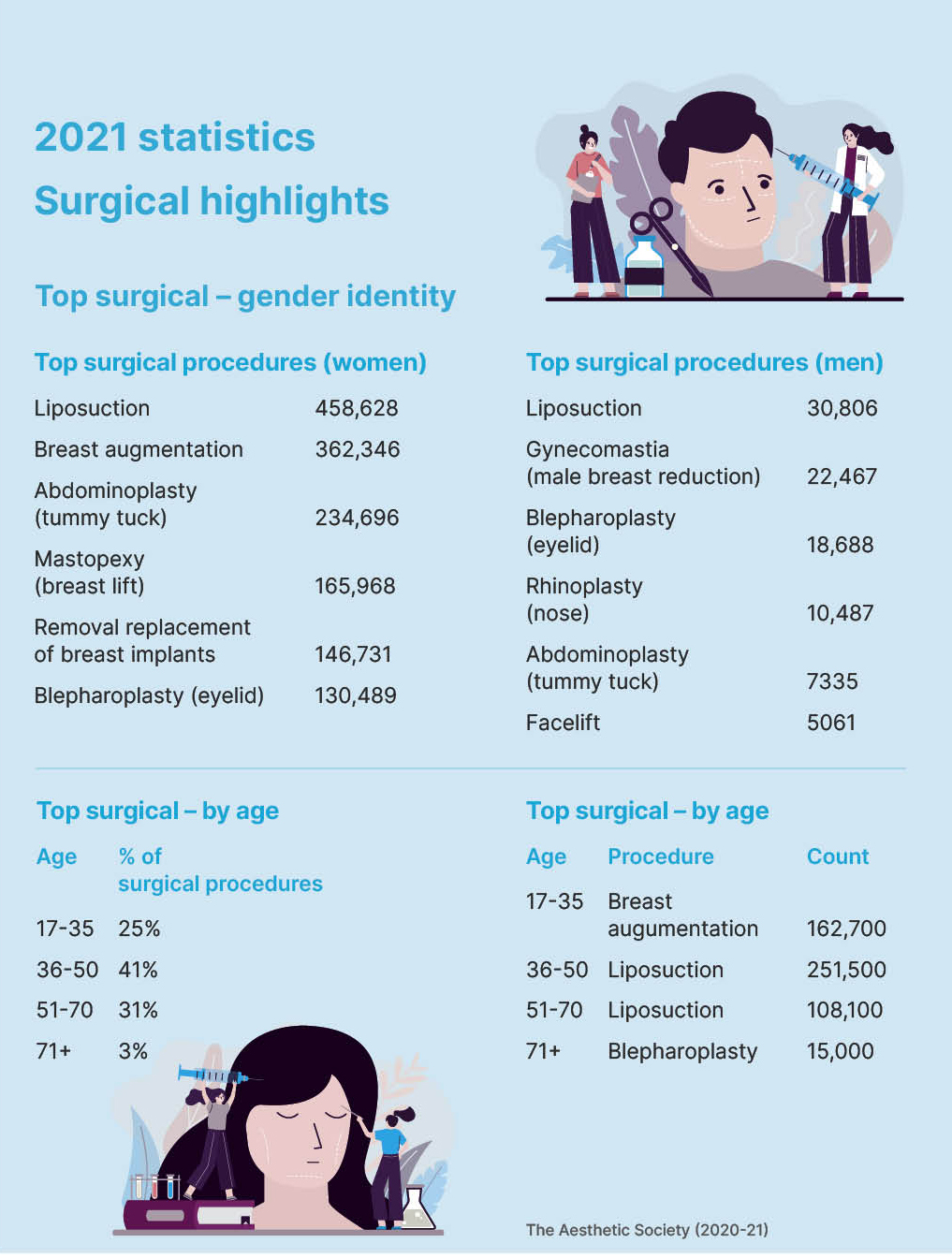

Australians are increasingly accessing cosmetic procedures, but exact numbers are unknown as statistics are not required to be reported. In the US, 15.6 million cosmetic surgical and non-surgical treatments were performed in 2020. After years of annual growth over the past two decades, the number of procedures decreased by about 15 per cent in 2020 predominantly owing to the impacts of COVID-19. It appeared that aesthetic procedures rebounded in the second year of the pandemic (2021) with surgical procedures increasing 54 per cent and non-surgical procedures increasing 44 per cent. In Australia, there were reports of people accessing their superannuation to finance cosmetic procedures during the pandemic. In terms of the most popular procedures in women and men, liposuction and botox were the top surgical and non-surgical procedures respectively, with 36–50 the most common age group to undergo procedures. With this focus on cosmetic concerns, it is important for psychologists to note at-risk groups, the implications for psychology and our role in treating negative body image.

Body image dissatisfaction and body dysmorphic disorder

Dissatisfaction with body image is the main motivator for people to undergo cosmetic procedures. Our sense of body image is formed by the thoughts, feelings, attitudes and beliefs we have about our bodies and how we look. Negative body image can be experienced by people of all genders, ages and backgrounds. Potentially anyone can have an interest in undergoing an aesthetic procedure as a perceived ‘solution’ for these concerns. However, people who actually undergo an aesthetic procedure tend to have higher body image dissatisfaction than population norms, particularly focused on the body part which is the focus of the procedure, e.g. nose for rhinoplasty.

It is no surprise the vast majority of psychological research in the field of aesthetic research has focused on body image related psychiatric disorders, particularly body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). However, I would personally like to take this opportunity to encourage researchers and clinicians in the field to extend their investigations to include a range of mental health concerns – mood disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, OCD, personality disorders and trauma disorders.

Nevertheless, it is important to review the BDD research in this area as a guide for future research and psychological evaluation. The exact criteria for BDD can be found in the DSM-5-TR. With the disorder focused on a perceived ‘defect’ or ‘flaw’ in appearance (something which is highly subjective), it is no surprise that people with BDD are far more likely to present to an aesthetic-focused health practitioner than a mental health practitioner. In fact, BDD is estimated to be experienced by 1–2 per cent of the population while the prevalence is 5–15 per cent in people seeking cosmetic procedures of all different types. Interestingly, research suggests that men and women are equally prone to developing BDD, but women (including those with BDD) are still much more likely to seek cosmetic procedures (around 90 per cent of total procedures are performed on women). The face, nose, skin and hair are usually the most common focus of concern, however, any feature or area of the body can be the focus. The criterion which really separates BDD from a sadly more ‘normative’ body image discontent is the distress and impairment on life domains. In some of the more severe cases of BDD, people will struggle to leave their home entirely for fear of other people seeing their perceived ‘flaw’ and potentially may isolate themselves from family members within their own homes.

Clearly, people with BDD are drawn to cosmetic procedures but what happens when they do undergo them? The vast majority experience no change or worsening of their BDD symptoms and this seems to be the case irrespective of the type of procedure. Therefore, there is a high likelihood of the patient being dissatisfied with the outcome. There is also the concern that BDD is associated with a high rate of suicide – the annual suicide attempt rate is 2.6 per cent, making BDD one of the most lethal psychiatric disorders. Not only is there the risk of harm to the individual, almost one-third of aesthetic surgeons have reported that they had been threatened legally by a patient with BDD. In addition, there are at least four documented cases of surgeons who have been murdered by patients who were likely to have a diagnosis of BDD. For all of these reasons, there is growing consensus that BDD contraindicates appearance-enhancing medical treatments.

Some recent research, including from my own team, has controversially suggested that BDD may not always be a contraindication to cosmetic intervention. A small number of studies in women seeking rhinoplasty and cosmetic genital surgery and men seeking penile girth augmentation unexpectedly found evidence of significant reductions in BDD symptoms post-procedure. It appeared that individuals with more mild to moderate BDD with a single appearance concern and realistic expectations for the procedure could potentially benefit from cosmetic interventions. Particularly with the genital-focused procedures, these have very specific objective outcomes – smaller labia minora, penis with a larger girth – which may potentially explain some alleviation in appearance concerns. However, there are several major limitations to these studies such as small sample sizes, limited range of procedure types investigated as well as not controlling for the impacts of other psychiatric disorders that may have been present. Perhaps most important is the lack of long-term follow-up after the procedure. It is entirely possible that the appearance focus shifted to another body part with the return of a BDD diagnosis and potentially further cosmetic procedure requests. It is a complex area that deserves far more research investigation. A diagnosis of BDD should still be taken very seriously in individuals considering cosmetic procedures.

The role of psychologists

To give a historical perspective, in late 2016, the Medical Board of Australia released Guidelines for Registered Medical Practitioners who Perform Cosmetic Medical and Surgical Procedures, which stated “The patient should be referred for evaluation to a psychologist, psychiatrist or general practitioner, who works independently of the medical practitioner who will perform the procedure, if there are indications that the patient has significant underlying psychological problems which may make them an unsuitable candidate for the procedure.” This was a great step forward in the field of cosmetic medicine. Such a mental health evaluation was never recommended previously to my knowledge and was a recognition of the need to protect the psychological safety of patients as well as physical safety. Some cosmetic surgery clinics around Australia were already routinely involving mental health professionals in the assessment and care of their patients, but, from my personal communications, this was seemingly not widespread.

The APS moved quickly to develop a set of practice guidelines. These were released in early 2018 to provide guidance to APS member psychologists undertaking assessments of individuals seeking cosmetic procedures, for their psychological suitability for such a procedure. I was very honoured to serve as an expert advisor on these guidelines so early in my career. Little did any of us know, these guidelines were actually a world first (at least to my knowledge) and I was contacted by professional bodies in both the UK and US to assist with their own psychological evaluation practice guides – a great achievement for the APS and all involved in the 2018 guidelines.

However, writing this article in 2023, five years after the APS practice guide was released, it is clear we need to move beyond this first step. The wording after “should be referred for evaluation” needs to be strengthened so it does not seem so optional. Furthermore, regarding “if there are indications that the patient has significant underlying psychological problems”, we must ask whether the cosmetic practitioner has suitable mental health knowledge to make that decision and what psychological problems should they be looking for? Speaking from my own clinical experience, there was not a substantial increase in referrals for evaluation of patients from cosmetic practitioners since the introduction of the guidelines in late 2016. How seriously were cosmetic practitioners taking this mental health evaluation recommendation from the Medical Board of Australia?

As such, I was heartened to see Ahpra and the Medical Board of Australia conduct an independent review of the regulation of medical practitioners who perform cosmetic surgery in 2022. The result was 16 recommendations to improve patient safety in the cosmetic surgery sector, some of which directly addressed psychological evaluation. Specifically, that “underlying psychological conditions such as body dysmorphic disorder” must be assessed using a “validated psychological screening tool” by the medical practitioner and that “the patient must be referred for evaluation” to an independent psychologist, psychiatrist or GP if the screen is positive.

Perspectives beyond BDD

At the time of writing this article, the public consultation on the draft guidelines has closed for submissions and we are awaiting further updates. It is great to see BDD specifically mentioned, but this is not the only psychiatric condition that should be considered in people seeking cosmetic procedures. Furthermore, as discussed above, there appears to be some controversy within the BDD field.

Ultimately, I hope that psychological evaluation will be made mandatory and this will mean that more psychologists will be conducting assessments for pre-procedure patients. Again, I have been fortunate to lend my expertise to the updated practice guide from the APS which will be released later in 2023. Like the earlier version, there are specific suggestions on how to conduct these assessments and provide feedback on the assessment to the client and referrer. There have been advancements in research in the past five years which have also been included, but there is still a great need for further research.

Finally, taking a broader perspective: we may only rarely encounter an individual in our professional psychology careers who is actively seeking a cosmetic procedure. It seems only a minority of psychologists in Australia are conducting pre-cosmetic procedure psychological evaluations, although this may increase if assessment becomes mandatory. Nevertheless, everyone we encounter has a sense of body image, which is core to our self-identity.

Sadly, we are commonly dissatisfied with our bodies. We would usually associate negative body image with disordered eating and eating disorder risk. However, poor body image has been linked to other mental health conditions including anxiety, depression, substance abuse and suicidality. Conversely, positive body image is associated with higher self-esteem, self-acceptance as well as engagement In positive health behaviours, such as protecting skin from potential sun damage.

As mentioned above, body image satisfaction is an issue which can impact anyone of any age, gender or background, not only girls and young women of European descent. A surprising number of senior males in my workplaces have disclosed their own body image concerns without me asking any prompting questions on the topic. Our bodies are the vessels which carry us through our entire lives. Of course they are important!

It is not vain or superficial to care or worry about the appearance of our bodies.

If not already doing so, I would strongly recommend making questions about body image a standard part of any general clinical assessment. You may be surprised at your discoveries and how this may be impacting the individual’s presenting issue. In this way, the forthcoming updated APS guidelines can potentially serve as a broader guide and not just inform those conducting the psychological evaluations for cosmetic surgery. Body image concerns and aesthetic issues are core business of psychologists. Let’s start asking about them!

For further information, please contact me via email. I’m particularly interested in hearing from psychologists conducting assessments and/or research in this space and/or those who want to become more involved.

Contact: [email protected]