This article outlines five key things learned through supervision following a complaint to the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). We discuss important topics such as “who is the client?”; parental responsibility; Gillick competence; The Privacy Act 1998; note taking; differences in policy and procedure between private and government sectors; the limits of indemnity cover, and family court processes. It concludes with a decision tree to guide professional choices about parental involvement in therapy.

I recently had an experience that many psychologists fear; a client lodged a complaint about me to AHPRA. The matters leading to the complaint began when the parents of a child I was treating separated. One parent withdrew consent for me to treat their child, while the other continued to attend with the child. Although I pursued regular professional supervision and legal advice, the ethical problems remained difficult to navigate. A number of issues were raised in the complaint to AHPRA, mostly around my communication with the non-attending parent.

As a result, the Board imposed as a condition of my registration a period of supervision about my consenting processes and communication with parents. This supervision revealed some incorrect assumptions that I held, which if corrected, may have prevented some of what happened. This article cannot substitute for your own supervision, legal advice or familiarisation with the APS Code of Ethics. However, I would like to share the five things I wish I had understood clearly before I went into private practice.

1. When working with children and their parents, it is essential to clearly identify the client.

A significant part of psychology training focuses on how to provide therapy and psychological services to willing, capable, adult clients. Of course, psychologists see many people who do not fit this description, however, the prototypical client is an individual person who is:

1. the recipient of the service,

2. the person making health decisions, and

3. the person paying for the service.

When all three of these roles are performed by the same person, ethical decision-making is simplified. However, while children can be the recipients of the service, their parents are typically responsible for making health decisions. Along with these responsibilities, parents also have certain rights, especially in relation to accessing their children’s health records.

There is no clearly defined point, or age, at which responsibility for decision-making transfers from parents to a young person who is still under 18. ‘Gillick competence’ is the way in which courts judge whether a child is a mature minor (Cox et al., 2017), and therefore entitled to make their own health decisions, including giving informed consent. Unless a court has deemed a child Gillick competent, or specified that only one parent – and not the other – is responsible for health decisions, the default position is that both parents have an equal right to make decisions about their child’s treatment. Therefore, each parent can have valuable and relevant input into therapy. We recommend that psychologists working with children ensure they are familiar with the APS ethical guidelines for working with young people.

2. Notes from child therapy are not confidential from their parents.

In Australia, the federal government regulates access to health records through The Privacy Act 1988 (Cth). In the case of children, in addition to making health decisions concerning their child, parents also have a right to access their child’s health records, which includes psychologists’ case notes. Ergo, anything written in a child’s file is accessible by either of their parents, including information provided by one of the parents alone, even if it is about the other parent and given in confidence. Even though a psychologist can refuse access if they believe it will be detrimental to the client’s wellbeing, this decision could be challenged in court. If a psychologist receives a request for access and the notes include sensitive information provided by one individual about another, it’s important to seek legal advice on how to best protect the confidentiality of this information.

It is important that parents understand up-front that anything disclosed to the psychologist can be accessed by the other parent or read out in a courtroom if it ends up in the case notes. The only way to truly keep information confidential is to not write it in the notes. Of course, psychologists have an obligation to keep sufficient and accurate records of sessions (APS, 2007) and to avoid being caught in triangulation. There is a need to strike a balance in note taking, since there must be enough detail for adequate service continuity of care, and inclusion of all relevant information, however, comprehensive notes place clients at risk of confidentiality breaches. Some helpful articles provide guidance on the purpose of notes and what to include in them. We recommend the article The dos and don’ts of client session notes from InPsych (October, 2012), and the article Record keeping in psychotherapy by Dr Robert King (2010).

3. Policies and procedures from other workplaces may not be appropriate for private practice.

Private practice is different from working for organisations and government departments. Legislation around privacy and freedom of information differs between the public service, small business, and the private health sector, and some legislation (e.g., mandatory reporting) also differs between states. Some organisations or government departments require staff to write detailed notes so that everything is documented clearly for others who may need the information in future. My previous experience working in schools was that I needed to write verbatim notes whenever a child makes a concerning disclosure, which were then given to the principal. However, this level of detail is neither necessary nor helpful in private practice. In private practice, there is no reporting hierarchy; the psychologist is solely responsible for all their decisions and actions.

We strongly advise anyone moving into private practice to seek supervision with experienced private practitioners. Ask about high-risk pressure points in their work and how they manage and prevent these issues. We recommend that all private practitioners reflect on how they developed their existing practices. If these processes were formed in a previous workplace, consider whether they are just as relevant or suitable to private practice. Do not assume that any previous workplace policies and procedures should be replicated in the private practice setting. We recommend working through the Private Practice Management Standards for Psychologists (APS, 2018) while considering these issues.

4. It is important that psychologists discuss ethical problems in supervision, but this does not absolve them of the consequences of their decisions.

A private practitioner is the only person accountable for all aspects of the service they provide to clients. Keeping adequate notes of decision-making processes can help mount a defence to a complaint, but it does not protect against complaints being made or an investigation regarding their practice. Nor does it prevent legal or disciplinary action being taken against the practitioner. AHPRA has a responsibility to protect the public from unsatisfactory professional conduct, not to protect health professionals from complaints.

Despite the best of intentions, a practitioner cannot be assured that the advice given in supervision is accurate. While the process of seeking supervision will be considered a mitigating factor, the onus remains on the practitioner to ensure their practice is compliant with their ethical responsibilities.

Professional indemnity cover insures psychologists for claims relating to litigation; that is, the costs associated with legal representation, including responding to a complaint made to AHPRA. However, in private practice, psychologists do not have the structure or support to deal with difficult legal matters that might be available when working for larger organisations. Typically, in private practice, there is no team leader or senior practitioner responsible for oversight of all cases and there is no legal department that can respond to lawyers on a psychologist’s behalf. Psychologists who hold indemnity insurance with Aon have access to free legal advice via the Aon legal hotline (bit.ly/3ujK4w5).

If private practitioners need legal advice beyond what is provided as part of their insurance policy, they will need to personally source and fund this. There is also the APS Professional Advisory service, which psychologists can call to discuss ethical issues. But again, even when professional or legal advice has been sought, the psychologist is solely responsible for their own actions.

When faced with difficult ethical or legal situations where there is no clear answer, the onus is always on the individual practitioner to decide on the course of action they will take. Sometimes, there does not seem to be an obvious way to resolve what seem to be competing obligations between legal requirements, ethical requirements, best practice and duty of care. Supervisors and lawyers may give conflicting advice. Making tough decisions with unclear advice and uncertain outcomes is a risk that psychologists need to be prepared to accept if they wish to work in private practice.

5. When disputing parents go to court, there is no guarantee their disagreements will be resolved.

When working with separating families, psychologists often become privy to some of the proceedings of the Family Court, especially if the Court subpoenas their case notes. Many people expect that when matters are brought to court, both parties have the opportunity to be heard equally, all evidence is considered and the Court attempts to resolve all disagreements by seeking a fair outcome that balances the interests of all parties. However, it’s important to be aware that where litigation is commenced, the court (e.g., the Family Court) can only answer the matters raised by the applicant for that particular hearing, even if there are other important issues between the parties. Most court applications require their own hearing, including any appeals of decisions made.

Each time this occurs, clients are required to pay for the legal services needed to access the Court until the matter is settled. This often occurs once the parties have spent tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars on legal fees. It is important that psychologists are aware that the court process may be very long and drawn out, and to avoid becoming involved as far as possible.

Consent and communication with parent clients

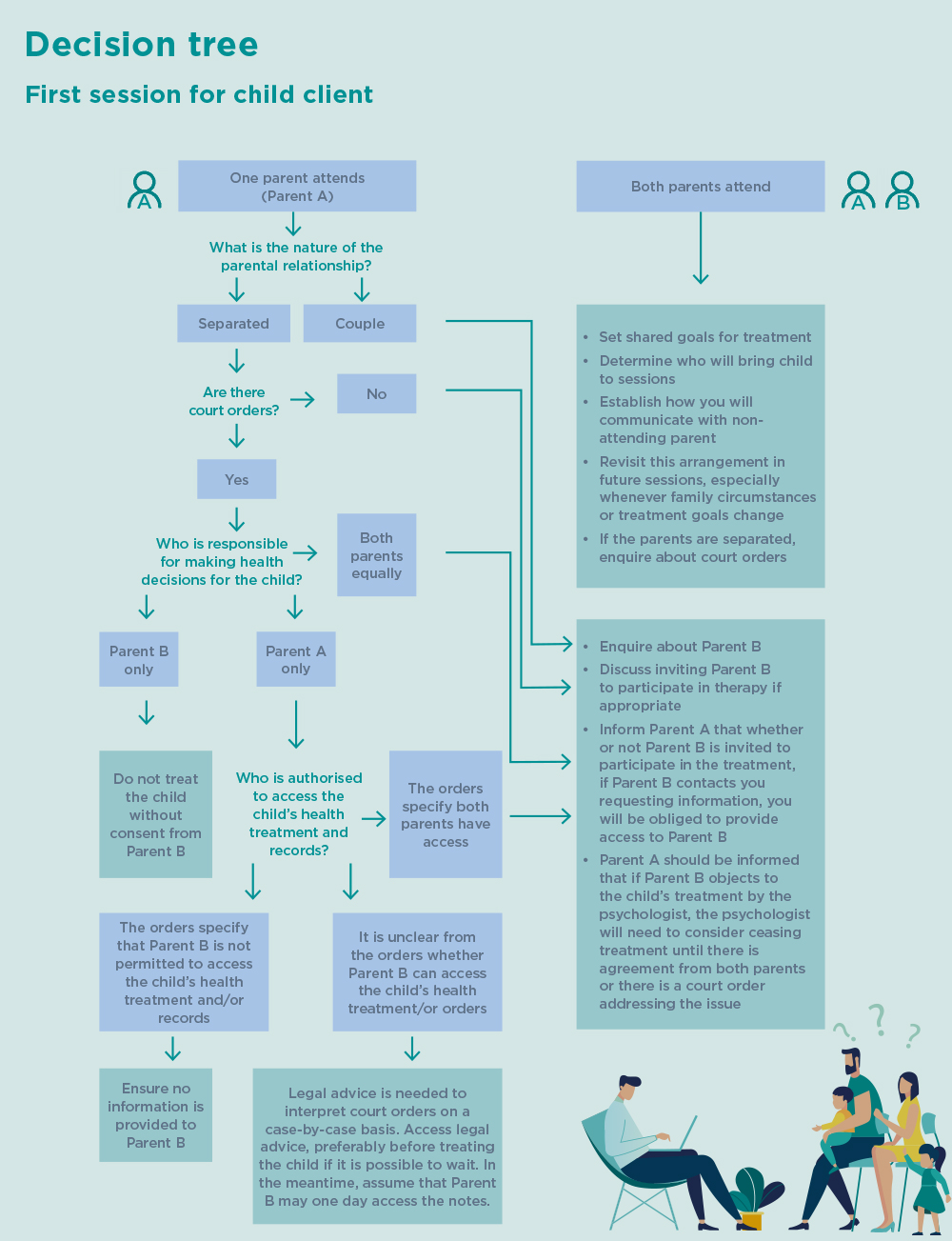

The decision tree has been created based on what I learned through my experience. I hope it will help other psychologists to prevent ethical issues when working with children and parents.

The questions in this chart need to be considered prior to the first session with each family. It’s important to establish whether the parents are together or separated and to make sure that either way, both parents are clear on issues of confidentiality and consent. It’s essential to have this conversation in the first session with the attending parent(s), and to enquire further about including the non-attending parent in future communication. It is also key to revisit this periodically, especially whenever family circumstances or treatment goals change.

Note: For the purposes of this diagram, Parent A refers to whichever parent attends the initial appointment on their own. This decision tree is intended to be an aid to decision-making, but it does not cover every scenario, and cannot substitute for receiving your own professional supervision and/or legal advice.

1Where first person is used in this article, it is written from the perspective of the first author.