Substance-related and addictive disorders are common and psychologists are well-equipped to screen, assess and treat symptoms in their practice. Implementing effective supports and treatments into our daily practice can occur via a range of strategies. While specialist treatments exclusively targeting pathways toward reduction or abstinence are options, they are often not within the scope of many psychologists working in generalist or many mental health settings. Regardless of the perceived barriers for integrating such practice into our work, there are key principles and approaches that can be adopted to improve the outcomes for many clients. Embedding appropriate practice across our clinical work requires an openness to consider evidence-based approaches for all levels of substance-related and addictive disorders.

This edition of InPsych includes articles on gambling, smoking, mobile phone use and other behaviours, and the impacts these have on the person themselves, their family, significant others and the community. All emphasise the fact that the behaviour should not be seen in isolation, but within a biopsychosocial model that takes into account environmental concerns, underlying causes and exacerbating factors of childhood, trauma, inadequate resources, and a range of personal and interpersonal issues. This introduction to the feature outlines a series of approaches that all practitioners can adopt for alcohol and other drug (AOD) presentations, based on the principles of harm reduction and empowerment of client’s choice. An emphasis is made toward outlining approaches that are consistent with best practice, easily accessible and do not require extensive resources to embed. Applying effective AOD treatments as a standard treatment component is achievable for all practitioners and is essential for achieving better outcomes for a high proportion of the community accessing treatment from psychologists.

Substance use and problematic behaviours

Addiction is defined as a chronically relapsing brain disease, which affects the brain’s reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. It is primarily a medical term, noted by the Australian Medical Association (AMA, 2017) and United States Office of the Surgeon General (2016). While the term ‘addiction’ continues to be used in AOD circles, it needs to be used carefully and in context as the related term ‘addict’ is most often used negatively, stigmatising substance users, implying shame and helplessness, and seriously impairing the road to recovery. Most importantly, the use of addict as a descriptor is labelling, reducing the person’s status in the world to this one identity. We have made the change in other areas – ‘person with schizophrenia’, ‘person with depression’ – and similarly, ‘person with a substance use disorder’ reminds us that our clients are people first and substance using individuals second. Focusing on recovery provides a sense of positivity to overcome struggles, and emphasises the person’s strengths. Conversely, labelling someone an addict focuses on weakness and failure.

Likewise, diagnostic criteria have evolved to reflect less stigmatising language such as removal of the term ‘abuse’. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; APA, 2013) replaced the categories of substance abuse and substance dependence with the spectrum of ‘substance use disorder’. The symptoms associated with a substance use disorder fall into four major groupings: impaired control, social impairment, risky use and pharmacological criteria (i.e., tolerance and withdrawal). ‘Craving’ has been added to the criteria and for the first time, gambling disorder is included and internet gaming disorder is noted as a condition for further study.

What we know about AOD use

Alcohol and other drug use are common human behaviours. The vast majority of adults have some form of substance use in their lives, however there is tremendous variation in the amount and type of substances consumed by different individuals over the lifespan. This may also be influenced by laws regarding the legality or illegality of certain drugs. This is often politically driven and has little to do with the level of use or possible harm that the drug itself, might cause. Early results from the most recent National Drug Strategy Household Survey (AIHW, 2017) paint an overall positive picture of Australian’s use of substances.

Smoking

Tobacco use has declined dramatically since 2001, when 19.4 per cent of the population over 14 years were smokers. A decade earlier, this figure was 24.3 per cent. In 2016, 12.2 per cent of people aged 14 or over were daily smokers, however, the daily smoking rate did not significantly decline from 12.8 per cent over the most recent three-year period (2013 to 2016). The average age at which 14- to 24-year-olds smoked their first full cigarette increased from 14.2 years in 1995 to 16.3 in 2016 (a significant increase from 15.9 years in 2013) and fewer teenagers are smoking (AIHW, 2017).

Alcohol

There have also been some important changes in alcohol consumption, which is considered at a global level to be the substance responsible for the most overall harm (Nutt et al., 2010). Compared to 2013, fewer Australians drank alcohol in quantities that exceeded the lifetime risk guidelines (17.1 per cent compared with 18.2 per cent). Importantly, young adults were drinking less in 2016, with a significantly lower proportion of 18- to 24-year-olds consuming five or more standard drinks on a monthly basis (from 47 per cent in 2013 to 42 per cent in 2016). However, while fewer 12- to 17-year-olds were drinking alcohol and the proportion abstaining significantly increased from 2013 to 2016 (from 72 to 82 per cent), a higher proportion of people in their 50s and 60s were drinking 11 or more standard drinks in one drinking occasion (from 9.1 to 11.9 per cent and from 4.7 to 6.1 per cent respectively) (AIHW, 2017). This is an important fact for psychologists working with this population group, as the impacts on mental health and family wellbeing may be significant.

Pharmaceuticals

Conversely, the rate of misuse of pharmaceuticals remains high. In 2016, 1 in 20 Australians misused a medication in the past 12 months (mainly over-the-counter and prescription codeine) (AIHW, 2017). Of major concern, however, is the rise in prescription rates of opioid medications, and particularly oxycodone to older adults. While the prescribing of morphine has decreased, hospital separations for ‘other opioid’ poisonings doubled between 2005-2006 and 2006-2007, and from 2001-2009, there were 465 oxycodone deaths (Roxburgh, Bruno, Larance & Burns, 2011). From 2002-2009, there was a substantial increase of 60 per cent in opioid analgesic dispensing rates – and a 180 per cent increase in oxycodone prescribing (Hollingworth et al., 2013). While it is likely this was directed towards patients with chronic pain (particularly back pain) and cancer pain, these drugs can also be used non-medically, and are easily crushed for snorting or injecting. Nielsen and colleagues (2013) found in their study of 204 people using drug treatment services in Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania, that half had frequently used oxycodone, with 86 per cent reporting problematic use. Importantly, more than 80 per cent reported initial use of the drug for pain relief.

Psychologists are often involved in working with clients with chronic pain. While we are not the prescribers, it is vitally important we understand the benefits and limitations of opioid medication for chronic pain. Chronic pain is a highly complex phenomenon, influenced by a range of factors, including psychological, social and psychiatric factors, by culture, social support and comorbid presentations (Rosenblum, Marsch, Joseph, & Portenoy, 2008). Clinical trials do not provide evidence of long-term effectiveness for opioid medications for chronic pain, although there is support for use with acute pain. There is growing concern that we have moved to a point of overtreatment (White & Kehlen, 2007), particularly given the serious concerns associated with misuse, addiction and diversion.

Illicit drugs

It is vitally important as psychologists that we separate fact from fiction, particularly in relation to illicit drug use. We have all heard the alarming stories of ice (a form of methamphetamine) use – however results of the 2016 survey showed declines in meth/amphetamines (from 2.1 to 1.4 per cent), hallucinogens (1.3 to 1.0 per cent), and synthetic cannabinoids (1.2 to 0.3 per cent). Nevertheless, people’s perceptions of illicit drugs, and particularly their rating of the major drug of concern, changed considerably between 2013 and 2016. According to survey results, a greater number of those surveyed now consider meth/amphetamines to be more of a concern than any other drug (including alcohol) and a greater number thought it caused the most deaths in Australia (AIHW, 2017). Health professionals, including psychologists, should challenge this perception (see article on page 20).

Amphetamine was first synthesised in Germany in 1887 (Rasool, 2009) and methamphetamine synthesised in Japan from ephedrine in 1893 (Grobler, Chikte, & Westraat, 2011). These drugs have a long history, but were not used pharmaceutically until 1934, when they were initially sold as an inhaler and decongestant (Rasmussen, 2006). Both Allied and Axis forces used methamphetamine during World War II for its stimulant and performance-enhancing effects (Defalque & Wright, 2011; Rasmussen, 2006, 2011). Eventually, as the addictive properties of the drugs became known, strict controls were imposed by governments, and as is the history of many drugs, they moved from legal to illegal status (Rasmussen, 2006).

The role of the psychologist

Psychologists have an important role in the treatment of substance use, particularly as they are often working within primary healthcare with clients and family members. It is crucial for psychologists to adequately and routinely screen and assess substance use and other addictive behaviours. As well as utilising diagnostic criteria, there are several other screening tools that are freely available online including the AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test), DUDIT (Drug Use Disorders Identification Test) and DAST (Drug Abuse Screening Test) that may flag substance use issues. If screening tools indicate that problematic substance use is occurring, information should be collected for each substance on quantity, frequency, duration, route of administration (e.g., smoking, injecting) and patterns of substance using behaviour. Evidence-based interventions and strategies to address substance use exist, and many psychologists have existing skills in the application of these interventions for other client presentations.

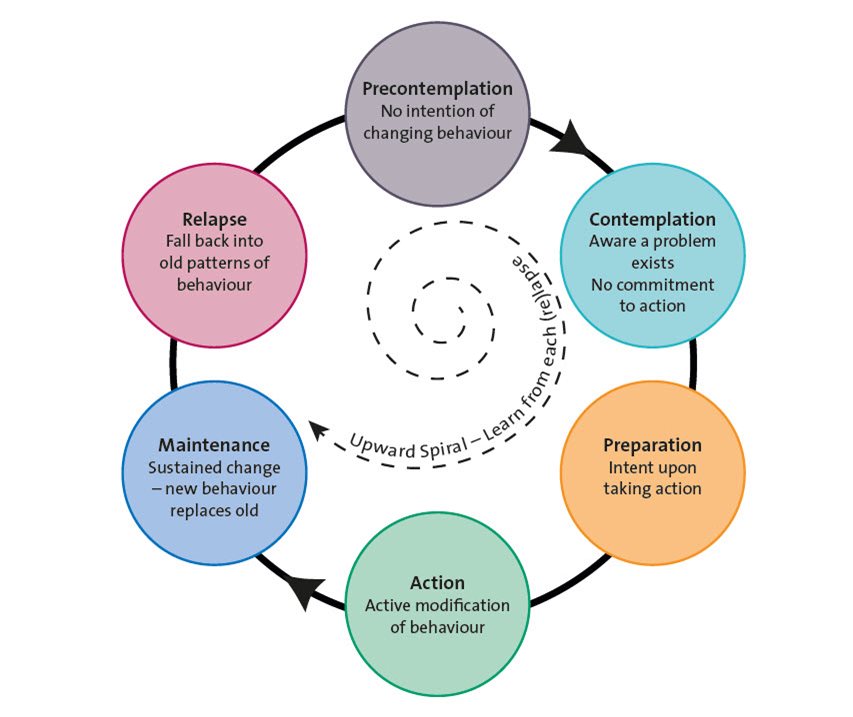

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a commonly used technique that involves a goal-oriented, collaborative conversation that aims to strengthen a person’s motivation and commitment to making change. This model views motivation as a state rather than a trait, and recognises that ambivalence is normal and resistance is not a force to overcome. The MI technique is matched to a person’s Stage of Change, which is a framework based on assisting a person to take action and maintain change (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stages of Change (Prochaska, DiClemente & Norcross 1992).

Substance use may be viewed as a symptom of underlying issues. There is a strong connection between trauma and substance use, often as a form of self-medication to deal with the underlying pain. It is estimated that as many as 80 per cent of women seeking treatment for risky drug use report lifetime histories of sexual and/or physical assault (Hein et al., 2009). This highlights the importance of effective treatments that concentrate not only on the substance, but most importantly, the underlying issues in working with this high-risk population.

While the evidence is emerging, there is increasing clinical interest in the application of third wave psychotherapies in the treatment of substance use disorders, specifically acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Strategies based on mindfulness resonate with some substance users where the focus is on acceptance and normalising internal experiences rather than eliminating them. Trauma-focused work, including the use of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) and narrative exposure therapy (NET) have a growing research base with this population.

In practice, AOD presentations are often crisis-driven and associated with a high rate of missed appointments and this should also be considered in any treatment plan. Where the client is engaged in the process, structured therapies can be utilised. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) are evidence-based in the treatment of substance misuse, and can be useful for managing thoughts and regulating emotions around substance use to prevent relapse. For clients using alcohol and other drugs, lapse and relapse are seen to be common and as such, relapse prevention should be considered from the outset of treatment, regardless of the approach used. This includes recognising the difference between lapse and relapse, developing strategies for high-risk situations, and ensuring adequate social supports to maintain change.

Self-help is an avenue that is generally recommended for clients with mild substance use disorders, or as an adjunct to treatment where the substance use is higher in severity or complexity. Options for self-help are usually drawn from a combination of approaches. These may be in the form of books, manuals, or online interventions. Peer-based group work (AA, NA, SMART Recovery) is also used as a standalone or adjunct treatment for substance use disorders for some clients.

A shared-care approach

As part of a primary health response, psychologists are often the first port of call when change is contemplated. However, there are some instances, particularly where the substance use is severe or where there is complexity of underlying issues when the client will need specialised treatment such as pharmacotherapy (opiate replacement), monitored withdrawal management (detox) or residential rehabilitation, including therapeutic community referral, as an appropriate treatment pathway. It is therefore important to work collaboratively with other services to ensure the best outcomes for clients within a shared care approach.

We no longer think of comorbidity as the exception – but rather the expectation. This means that clients will present with a range of issues, often quite complex. There is always a purpose to substance use – sometimes it is for pleasure, and often it is to deal with and cover physical and emotional pain.

| For questions and resources |

|

The National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline (1800 250 015, available 24/7) provides information, counselling and a referral service for clients and significant others as well as information for health professionals about local treatment services.

The Australian Drug Foundation provides information at www.adf.org.au and clients can access immediate online counselling at www.counsellingonline.org.au.

The Psychology and Substance Use (PSU) Interest Group offers members an opportunity to access relevant CPD and engage with other psychologists with an interest in the area.

|

The first author can be contacted at [email protected]