The following article outlines an innovative program in Western Australia, a State that has a long history of specialist psychology titles and where positions within the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) are almost exclusively clinical psychology and clinical neuropsychology positions. To this end, the article refers to clinical psychology positions, however, the professional standards framework is relevant and could potentially be applied to all psychology trainees and professionals.

Western Australia (WA) has a long history of clinical psychology in the public health sector, with University of Western Australia being the second university in Australia to establish a post-graduate qualification. The establishment of the WA Registration Board in 1978 with specialist title in clinical psychology at the beginning of the 1980s also helped ensure a steady stream of appropriately qualified graduates. Health Department structures in mental health reflected this, with a Principal Clinical Psychologist first appointed in 1969 (Smith, 1999).

Psychology in Western Australia: The historical picture

In 1990, decentralisation of mental health and separate hospital structures saw the abolition of this position and oversight around the functioning and standards of clinical psychology in health, with only Clinical Psychologist and Senior Clinical Psychologist positions remaining. Competent clinical psychologists became demoralised and left in large numbers, leaving vulnerable young and inexperienced clinical psychologists to guess at the level and type of skill they needed for the work, and with no way of determining progression or appropriate professional practice in this specialised environment. Things in the public sector did not look good.

Managers too struggled with this. There was no way of knowing whether or not their clinical psychologist was providing a professional practice to the best of their ability, or what they might expect of a similar person of the same profession, or a way of addressing things if they were not sure.

The changes that matter

From time to time, particularly significant changes and shifts in the public sector happen, in the same way that Medicare funded psychology services produced a significant shift in the private sector.

In the mid 1990s clinical psychologists began to register their concerns with the WA Industrial Relations Commission. Consequently, in 2002-2005, a series of industrial outcomes saw a significant shift to all clinical psychology positions in Health based on skills, adequately renumerated with four levels of professional structure. These were: Clinical Psychologist Registrar, Clinical Psychologist, Specialist Clinical Psychologist (a title later changed to Senior Clinical Psychologist (SCP) to comply with AHPRA requirements) and Consultant Clinical Psychologist (CCP). The fundamental change was the recognition of work value as the principle for the establishment of higher-level positions: how many, if any, positions managed was irrelevant, it was the value of the work undertaken which was of pivotal importance. SCPs were required to research and develop new programs in the area in which they worked, supervise, teach in the sector, and consult. SCPs had to be very good at the particular area they worked in, such as pain or early psychosis. To solve the problem of professional governance at the local level, some SCP positions also had coordination duties attached (SCPC’s).

In the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) setting, the position of Consultant Clinical Psychologist (CCP) was established, responsible for professional standards, teaching skills, research of Statewide significance and liaising with agencies/ universities to develop practice innovations. One of the first tasks identified by the CAMHS CCP was establishing a professional standards framework.

Professionally focussed innovations: Setting a professional standards framework

Public sector innovations need to be economical and demand little of the system, and they must add value. This is the reality of working with other people’s money. Governance is crucial.

The big challenge for the CCP was how to achieve consistent professional standards in the most economical fashion across the sector, and provide the sort of standards and support that would result in a high level of practice and a system of accountability for professional practice.

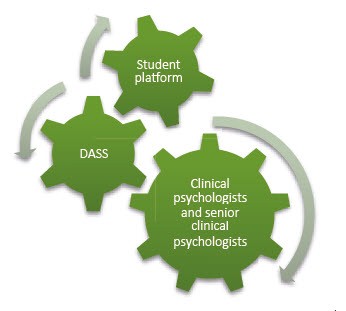

Government organisations understand structure. To establish and maintain professional standards, an education and training structure for CAMHS clinical psychologists was developed.

Level 1: Clinical Psychology Student Platform

To support consistent development whilst on placement, the CAMHS Clinical Psychology Student Platform was developed. Senior clinical psychologists in CAMHS conduct fortnightly seminars on a range of CAMHS relevant topics. The platform has the added bonus of encouraging senior clinical psychologists to stay on top of new aspects of the field – no one asks probing and relevant questions quite like students. The platform operates on a semester timetable and seminars are held at the SCP site, further increasing the exposure of trainees across the system. Trainees may be in one of a number of diverse settings during their placement – community clinics, specialised clinics such as Multi Systemic Therapy or eating disorders, or inpatient units. Trainees are advised to discuss the seminars they attend with their CAMHS placement supervisors, who can also gain access to materials, assuring all are on the same page.

Level 2: Registrar development and support system (DASS)

When employed with CAMHS, the DASS (Development and Support System for clinical psychology registrars) is offered to registrars. DASS meets every three weeks to focus around complex cases. DASS aims to provide registrars with a consistency of skill development that will facilitate registration, allow the easy transfer of skills across CAMHS settings, and reduce the burden of intensive supervision on individual CAMHS supervisors. An SCP leads this with the CCP. Skills and exposure of registrars are variable from cohort to cohort. The SCP and CCP keep an eye on the focus of complex cases and general weaknesses, so that specific seminars can be organised if needed in particular areas, again by SCP’s within the system.

Platform seminars are also available to DASS participants to plug any gaps and from time to time DASS participants have combined learning experiences with child psychiatry trainees. As part of the structure there is thus a continuous interactive system between clinical and senior clinical psychologists and students and registrars, which enhances the knowledge base of all.

Level 3: Refresher training for clinical psychologists and senior clinical psychologists

Refresher training is a concept easily understood by health organisations, where skills based refresher training happens to counter the recognised phenomenon of slippage of skills. Nominating content rests principally, although not exclusively, with CAMHS clinical/senior clinical psychologists. Training happens via organised innovative partnerships with universities, test distribution companies and across services, to provide clinical psychologists in the system with what they need to do their job well without cost. The frequency preference for clinicians is once every two months. A recent survey found the current priorities included updates on evidence-based practice (75%); psycho-legal issues (68%); and assessment and therapy with children under five years of age (53%) (Miles, 2016).

All clinical psychologists are encouraged in their first two years with CAMHS to take advantage of the Platform seminars to plug gaps, some may also attend DASS.

Level 3 plus: The important role of the SCP coordinators

In this model the responsibility of the coordinator is to detect when there is a consistent problem across the clinical psychology workforce, using the evidence of a number of Individual Performance Reviews (IPRs), which are conducted jointly with managers. This allows managers to also have input into the system.

All CAMHS employees are required to have supervision arrangements. Generally for senior staff this will consist of peer supervision or specialised external supervision. The framework encourages an economical use of supervision by grouping people of similar needs together for simultaneous education, minimising the need for this education in supervision and providing consistency of understanding.

All SCP’s are expected to take some role in the structure, teaching or supervision. The former is sometimes a springboard to teaching more broadly in the health system and helps develop these skills.

Ten years on from the changes that matter

Many things have happened in the last ten years, through a time of two organisational changes for CAMHS in WA. The Professional Standards Framework has continued to prove useful. Like all worldly things, hopefully other, better things will eventually supersede it.

An example of the professional standards framework at work: The PATI

Several years ago, it became evident through DASS and the IPR review system that many clinicians were struggling with integrating current knowledge of interventions and the complex patient factors that are often affecting CAMHS patients, and who are frequently quite vulnerable. This led to the development of the PATI (Jones, M., 2015). The PATI is an evidence-based trouble-shooting tool for psychological intervention with complex child and adolescent mental health difficulties.

It provides a framework for looking at:

- Patient factors,

- Assessment factors,

- Therapeutic Alliance factors, and

- Intervention factors.

The PATI allows a systematic approach to addressing complex cases and is currently used in CAMHS in a range of ways and contexts including in individual and peer supervision, individual reflection on a case, in team and review meetings, and in teaching.

|

The author can be contacted at [email protected]