Cancer is the leading cause of disease and injury burden in Australia, accounting for nearly one-fifth of the total disease burden. In 2007 over 108,000 people were diagnosed with cancer and nearly 40,000 people died from this disease (AIHW, 2010). In Queensland, the third largest Australian state by population with an estimated resident population of 4.5 million (2010), nearly 22,000 people were diagnosed with cancer and approximately 7,000 deaths were recorded in 2007 (Queensland Cancer Registry, 2010).

Improvements in early detection and treatment mean that many people are surviving and living with the consequences of cancer. While there have been significant improvements in outcomes from cancer, these improvements have not been seen in all population groups. Those diagnosed with cancer who live in rural and remote areas, and areas of disadvantage, have significantly poorer survival compared to those living in major cities. In Queensland – the most decentralised state in Australia with approximately 40 per cent of the population living outside the capital city and surrounding area – it is estimated that nine per cent of cancer deaths could be postponed beyond five years after diagnosis if the survival rates of rural and remote cancer patients were the same as the Queensland average (Cramb et al., 2011).

Significant disparities also exist in psychosocial outcomes for rural and regional cancer patients. Living in rural areas has been associated with greater unmet needs, with a recent study undertaken in a regional cancer population finding almost two-thirds of cancer patients reported at least one moderate to high unmet psychological need (McDowell, 2010). Futher evidence suggests that rural women diagnosed with breast cancer may perceive, or actually have, less control over treatment decisions, and this may be due to limited access to information about breast cancer treatment options (Davis et al., 2003).

Levels of distress associated with cancer

The diagnosis and treatment of cancer is a major life stress that is associated with a range of psychological, social, physical and spiritual difficulties, with rates of distress among cancer patients up to 47 per cent (depending on sample and assessment used), and rates of clinical anxiety and/or depression in the order of 30-40 per cent (Mitchell et al., 2011). Although over time most people diagnosed with cancer adjust effectively to their changed life circumstances, as many as one third experience heightened distress that persists or even worsens over time. In addition, many partners of cancer patients report high levels of distress, sometimes even greater than that of the patient.

Psychosocial care that includes screening for distress and referral for psychosocial interventions is endorsed as an international standard in cancer care (International Psycho-Oncology Society, 2010). Yet implementing this standard is particularly challenging in regional and rural areas where access to psychosocial services is limited. Queensland’s geographically decentralised population creates inequalities of access and has a significant impact on psychosocial outcomes for people distressed by cancer. Telephone delivery of psychological services can help address these issues.

The Cancer Counselling Service

In 2004 the Cancer Council Queensland developed the Cancer Counselling Service (CCS) to address the psychosocial needs of Queenslanders distressed by cancer, particularly those in regional areas. The CCS is the first and only service in Australia staffed by psychologists to provide specialist psycho-oncology interventions via the telephone to cancer patients and their loved ones.

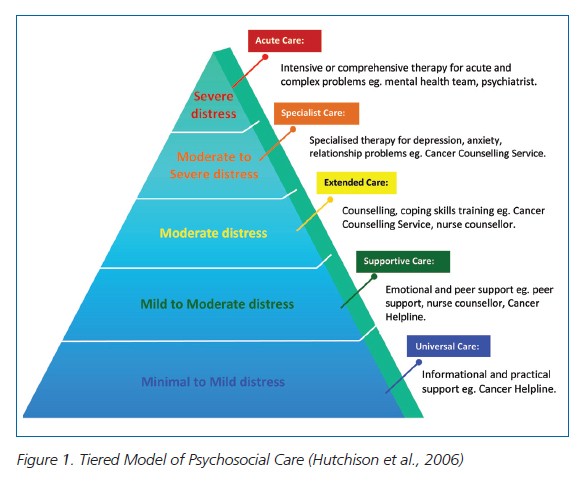

The CCS is embedded within a stepped care model of intervention that provides progressively higher levels of care for increasing levels of distress (Figure 1). Initial levels of care are provided by the Cancer Helpline, a toll-free cancer information and support service staffed by oncology nurses and other health professionals to deliver informational, practical and emotional support, and includes screening for distress and triage to higher levels of care (Hutchison et al., 2006).

The CCS provides in-depth psychological care (Extended and Specialist Care in the Tiered Model) that includes counselling and coping skills training, through to individual or couple therapy for mood and anxiety disorders or significant relationship/sexual problems. The service draws on current best practice guidelines for effective psychosocial interventions for people distressed by cancer. Intervention comprises up to five sessions of semi-structured therapy designed to target challenges commonly experienced across the illness trajectory, and a range of therapy materials and patient resources are utilised to augment therapy.

Support is delivered by telephone to enable people to access care regardless of geographic location; and face-to-face services are also available in Brisbane, Gold Coast, Townsville, Cairns, and more recently Rockhampton and Bundaberg. Patients and family members with severe or complex support needs are appropriately referred to acute care or multidisciplinary mental health services.

Since 2004, over 2,250 people from regional areas of Queensland have received psychological intervention for cancer-related difficulties from as far north as Bamaga on the mainland and Thursday Island in Torres Strait, to Mt Isa and Boulia in the west, east to Magnetic and Stradbroke Islands, and south to Stanthorpe, Goondiwindi and into Northern NSW. Data for the 2008 calendar year indicates 230 referrals were from regional areas, 54 per cent for people with cancer and 46 per cent for their partners or family members. A broad range of cancer diagnoses were represented with the most common being breast, bowel, gynaecological, lung and prostate. The majority were female (80%), aged 50-59, with 63 per cent older than 50 years. The most common presenting problems were adjustment to cancer, anxiety, survivorship issues and anticipatory grief.

Mindfulness and cancer

The use of mindfulness-based interventions in health care settings is rapidly growing, and involves open awareness of current experience and the intention to observe habits of reacting as they arise. Qualitative studies of mindfulness for cancer patients have identified positive changes in acceptance, self-control, personal growth, shared experience and self-regulation. A recent Australian randomised control trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) showed that cancer patients experienced significant improvement in depression and anxiety and a trend for improved quality of life compared to a waitlist control (Foley et al., 2010) and a recent meta-analysis of mindfulness-based stress reduction in cancer patients reported moderate positive effects on psychological distress (Ledesma & Kumano, 2009).

Since 2009, the CCS has run 8-week MBCT programs for cancer patients and family members. A total of six groups (49 participants) have been conducted in regional offices, including a combined face-to-face and telephone group in Rockhampton. In future telephone and/or web delivered groups will be further explored.

Conclusions

The Cancer Counselling Service demonstrates that psychosocial interventions for cancer can be effectively delivered regionally, and that the needs of many people in regional and rural areas would remain unmet if not for the broad reach of a telephone-delivered service.

Although working over the telephone can present challenges, for people unable to access face-to-face services it is a worthwhile and viable alternative. Telephone has advantages over text-based web delivery including personal contact with the therapist, verbal expression of concerns, and tailoring of intervention to individual circumstances. In the future we envisage making use of technology (including voiceover internet protocols) to more closely replicate face-to-face therapy over distances, as well as having a variety of web-based services available (self-management materials, structured self-paced therapy programs, real-time web therapy). However, with cancer being more common with older age, the current generation are more universally likely to utilise telephone rather than internet delivered services, thus making telephone the most effective and economical option for remote delivery at the present time.

Some client groups are more difficult to service via telephone, such as hearing or speech impaired and culturally and linguistically diverse groups, including Indigenous Australians. Although telephone translation and relay services are available, face-to-face service delivery is likely to be more effective for these groups. Service to men remains a challenge, and although an issue for psychological services generally, a greater understanding of the types of services men would prefer to access and the methods to best promote services to men is needed. In our programs and research we have done considerable work with men with prostate cancer and continue to enhance our understanding of the needs and preferences of this group.

In summary, tele-based services to deliver psychosocial interventions for cancer have broad reach and overcome a range of barriers to access, including health status, finances, transport/inability to drive, and carer responsibilities. These services also cater to those who are less likely to access face-to-face services and prefer the anonymity of a telephone service, thus increasing access to a subgroup who might otherwise avoid seeking help. In addition, tele-based services have potential for national implementation, increasing access to high quality evidence-based psychological support and interventions for all Australians with cancer who are experiencing significant psychological distress.

The principal author can be contacted at [email protected] .