Sorting through the maze with mentalization based treatment (MBT)

Article summary:

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a disabling and prevalent psychiatric disorder associated with a high burden of individual suffering.

- BPD represents a challenge to clinicians and policymakers alike. Choosing an effective evidence- based treatment tailored for BPD is fundamental to the successful management of this disabling condition and to providing cost-effective mental health services.

- This article outlines the accumulated evidence for mentalization based treatment (MBT), its adaption across the globe and the current place of MBT in Australia. Increasing implementation of MBT offers a solution to the BPD treatment puzzle.

Many individuals with BPD consistently demonstrate high service utilisation with significant associated societal and financial costs. Successful treatment of BPD is therefore vital in reducing the burden of suffering and such costs. A meta-analysis of health care costs of BPD and the benefits of treatment found cost savings of USD $2,988 per person per year resulted from the provision of any psychological therapies to treat BPD (Meuldijk, et al., 2017). More importantly, therapies specifically designed to treat BPD have a substantially higher cost saving than Treatment As Usual (TAU). The analysis revealed that the provision of evidence-based therapies for BPD delivers additional mean cost savings of USD $1,551, when compared to TAU (Meuldijk, et al., 2017). The cost benefit when we compare tailored treatments for BPD with TAU is persuasive. With a population of 26.5 million and a frequency of BPD between 1 and 2 per cent, Australia can currently expect between 265,000 and 530,000 patients who live with BPD. Continuing with TAU, which results in much less economic savings, looks expensive from this angle.

Uncounted costs

In estimating the costs of BPD most studies calculate direct and indirect costs as they apply to the individual with BPD. Additional costs such as providing services to family members, parents, partners and children of a person suffering with BPD are generally not included in these calculations. This is desipte the fact that many specialist public BPD services and therapies (such as dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) and MBT) routinely provide services for family members. Moreover, studies have also shown that spouses of patients with BPD have increased societal cost compared with matched controls (Hastrup, et al., 2019). Such findings suggest that actual costs associated with BPD may be even higher than most study estimates.

As clinicians, we rely on the development of quality treatment guidelines that evaluate the evidence and make recommendations for approaches to treatment of disorders such as BPD. Numerous international guidelines for the treatment of BPD have delineated the essential features of a well-structured BPD treatment that are required to achieve best outcomes for this population, for whom TAU may well be inadequate and therefore expensive. Specifically tailored programs with specialist training required to deliver interventions (such as exists for MBT) have now been included in most national and international guidelines for the treatment of BPD.Australia has such guidelines (NHMRC, 2012).

One of the most promising structured treatments for BPD is MBT. Several factors, which I will elaborate, suggest its adoption in Australia. First, MBT was specifically developed as a treatment for BPD and has a solid scientific basis being grounded in an accumulated body of research from disciplines including neurology, attachment theory, psychodynamic therapy, social cognition and human development to name a few. Second, MBT has been adopted by clinicians and services around the world, including the National Health Service (NHS) U.K., demonstrating MBT’s accessibility and applicability. Third, there is a growing body of evidence for MBT as effective for BPD, leading to it being recommended by several national and international bodies. Third, MBT has already been adopted by numerous services and clinicians in Australia. Moreover, there is also an existing structured training pathway for MBT with internationally accredited hubs in Australia. Clearly it is an evidence-based treatment when delivered by appropriately trained clinicians.

What is mentalization based treatment?

Professors Bateman and Fonagy, the architects of MBT, define mentalizing as:

“a form of imaginative mental activity about others or oneself, namely, perceiving and interpreting human behaviour in terms of intentional mental states (e.g., needs, desires, feelings, beliefs, goals, purposes, and reasons)” (Bateman & Fonagy, 2016)

Mentalizing is attentiveness to thinking and feeling in oneself and others; it is a very human capability that underpins everyday interactions. It involves a range of capacities that help us maintain self-coherence and, critically, understand our own and others’ behaviour as being organised by mental states. Whilst mentalizing can, and regularly does, fail the average person, persons with a personality disorder are particularly vulnerable to failures of mentalizing. They can lose cognitive and emotional coherence in moments of relational stress. Indeed, the difficulties experienced by those with personality disorder arise from the fact that their mentalizing is lost more easily, especially in a relational context, and is more difficult to recover.

Bateman and Fonagy (2016) saw that difficulties with mentalizing underlie the phenomenology of BPD - the unstable experience of self, impulsivity, self-harm and suicidality, emotional dysregulation and unstable, intense relationships. Based on this, MBT was developed as a short-term psychotherapy to treat BPD by specifically targeting mentalizing capacities. The aim of MBT is to identify mentalizing vulnerabilities that relate to the patient’s presentation, to attend to and stimulate mentalizing, to assist the patient recover mentalizing when it is lost and for the patient and therapist to develop a curiosity about each other’s minds and hearts.

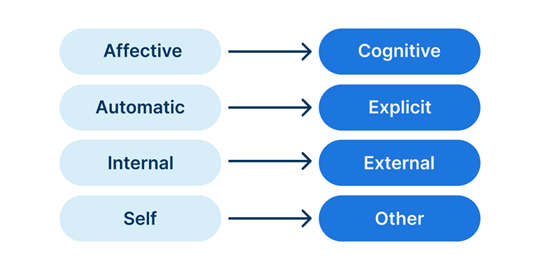

Mentalizing dimensions

To achieve this focus on mentalizing requires clinicians to be trained to understand the theory behind and the phenomenology of mentalizing and non-mentalizing. Dimensions of mentalizing have been well described by Fonagy and Bateman (2016). They have developed interventions which are aimed at correcting mentalizing which is dominated by one dimension to the exclusion of another.

Mentalizing is most functional when we can recruit from either polarity of these dimensions when needed. When we see things largely from a cognitive perspective, for example, we may expect logic and reason to prevail, to rationalize matters and be somewhat blind to the influence of emotions on ourselves and others. One can immediately see how this might complicate our relationships. Similarly, being predominantly emotionally focused (or overwhelmed as occurs in BPD) can lead to reflexive certainty about the minds of others. Intentions, feelings and thoughts of others are experienced as felt known, without the balance of being able to access alternative cognitive perspectives.

The result is an interpersonal reactivity to what is perceived as in the mind of the other, impulsively responding to an assumed meaning that is not easily altered. Even when presented with alternative perspectives regarding what was going on in the mind of the other, these are often not genuinely able to be taken up. Neither polarity of any of these four dimensions is considered preferable to the other, instead what matters is the flexibility to access and utilize either polarity when the relationship or situation requires it of us. The automatic, emotionally driven and rigidly held assumptions predominant in BPD make relationships fraught and painful.

Another way in which mentalizing can go awry is with the emergence of what are described as pre-mentalizing modes of experience. Three pre-mentalizing modes have been outlined, each of which would likely be recognisable to most therapists. These pre-mentalizing modes are very tightly held onto, with fixed ways of experiencing self and others and they consequently cause pronounced difficulties in self-experience and in relationships, including therapeutic relationships. The three modes are termed, psychic equivalence, teleological and pretend mode.

Psychic equivalence (Inside-Out mind)

In the psychic equivalence mode whatever is in the mind is perceived and being absolutely true and real. There is no bridge between the mind and reality. What is inside the mind is seen as representing reality. Such a state of mind can be extremely frightening and very painful. The patient who is in state of truly believing that “I am a bad person”, for example, is in a very precarious and risky state of mind. Psychic equivalence is marked by certainty of the beliefs held and without a bridge linking the mind to external reality is not open to alternative perspectives or external evidence. Psychic equivalence shows itself in patients whose mentalizing is imbalanced toward the affective and automatic poles of mentalizing dimensions.

Teleological mode (Outside-In mind)

In the teleological mode internal states can only be understood in terms of external, physical outcomes. Individuals in this mode perceive feelings, thoughts and intentions through witnessing an external outcome. “I must have been sad because I was crying” or “If he loved me he would have answered my text straight away” both reveal a perception about mental states as manifest in behaviours. In teleological mode the individual cannot accept anything other than physical action as a true expression of the other person’s intentions.

Pretend mode (Bubble mind)

In the pretend mode thoughts and feelings have become severed from any sense of real experience. Patients in pretend mode can discuss apparent thoughts and feelings, often at some length, but they lack any real connection to these feelings. In therapy this can lead to lots of inconsequential discussions of mental states that have no felt link to the patient’s internal experience. Painful feelings of emptiness arise from the individual’s limited capacity to experience an internal world and therefore to genuinely connect with another person.

In summary, serious imbalances within the mentalizing dimensions can sometimes tip over into the more rigidly held and more painful experience of one of the pre-mentalizing modes. Psychic equivalence results if emotion dominates over cognition. An over focus on external features to the neglect of internal can tip over into teleological mode. Pretend mode can result where reflective, explicit mentalizing is not well established.

Addressing BPD with an MBT approach

All therapies involve some mentalizing, so MBT in one sense is not unique in this regard. What is unique about MBT is that it specifically targets mentalizing capacities. The MBT therapist takes an inquisitive stance around the heart and mind of the patient seeking to make sense of the patient’s experience. Together patient and clinician attend to experiences where ideas and feelings begin to collapse into pre-mentalizing modes leading to destructive behaviours or intolerable feeling states. An MBT clinician does not try to compensate for the patient’s mentalizing failure with their own high level mentalizing, or speculation, by “explaining” to the patient what may be going on for them. Meeting low or non-mentalizing in the patient with our own clever mentalizing, however tempting, does not enhance mentalizing capacities in the patient.

Instead, in MBT we seek to stimulate mentalizing, to regain it when it is lost, to recover mentalizing using specific techniques developed for MBT. Essentially, the MBT clinician is alert to non-mentalizing both as it manifests in the pre-mentalizing modes and also when it is apparent that the patient is fixed at one of the poles of the mentalizing dimensions.

Evidence for MBT

The effectiveness of MBT in the treatment of BPD has been evaluated by a number of international bodies and treatment recommendations made as a result. In the United Kingdom NICE guidelines, MBT is one of only two recommended treatments for BPD, the other being DBT, and is also one of two psychological therapies recommended by the NHS for BPD. MBT is also one of two recommended treatments for BPD in the Finnish, Swiss, Dutch and German BPD guidelines. Australian BPD treatment guidelines found that MBT had Level II evidence in 2012.

There have been subsequent studies demonstrating the effectiveness of MBT. For example, in 2018 a systematic review of studies concluded that MBT is an effective treatment for BPD and that it “leads to reductions in borderline personality disorder-specific symptoms, such as profound interpersonal problems or suicidal behaviour, and common comorbid disorders, such as depression and anxiety” (Vogt & Norman, 2018). Another review (Castillo, Browne & Perez-Agorta, 2018) also found positive clinical outcomes for BPD in evidence, greater than for treatment as usual (TAU).

Interestingly, while further evidence is needed, these reviews also found that treatment of adolescents who self-harm, at-risk mothers and substance abuse showed promising results with MBT. There was also an eight-year follow-up of patients treated with MBT (Bateman et al., 2021) which showed that compared to TAU the number of patients at follow-up who continued to meet the primary recovery criteria was significantly higher in the MBT group (74% vs. 51%). The MBT group also showed better functional outcomes in terms of being more likely to be engaged in purposeful activity and reporting less use of professional support services and social care interventions.

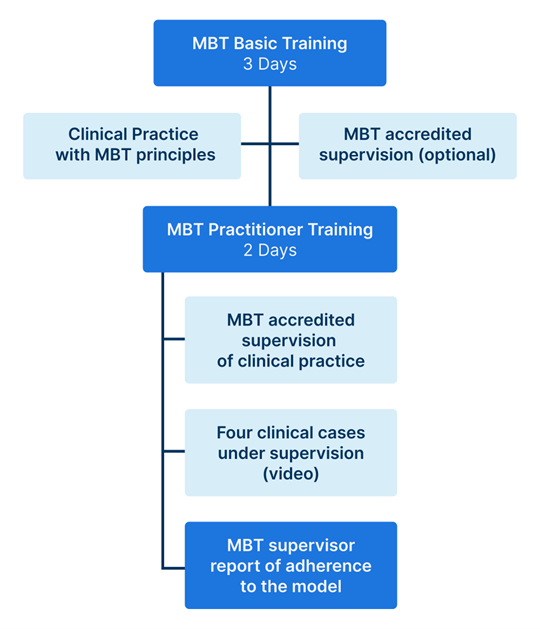

MBT training

Tailored treatments require well-trained clinicians to deliver treatments. MBT is favourably positioned in this regard as it has a well-defined and well supported international accreditation and training pathway. This helps to ensure adherence to the model, standards of practice, and appropriate skill level. Training includes clinical supervision, discussion of video recorded clinical material, supervised treatment of four cases of 24 sessions or more and the development of competence in the use of the MBT adherence scale to evaluate fidelity to the model.

The MBT training pathway*

*From Mentalization Based Treatment Australia Group

Established MBT training and treatment in Australia

MBT training and practice is already well established in Australia. There are three MBT training hubs, one in Western Australia, one in Victoria and one nationally, each with trainers and supervisors supporting MBT teams and individual clinicians. In addition to 60 or so formally accredited MBT practitioners, there are at least 11 accredited MBT supervisors as well as eight MBT trainers under license from the AFC to run MBT trainings in Australia.

The total extent of MBT being delivered in our mental health system is difficult to estimate, in part because the many private practitioners practicing MBT are not currently recorded. However, MBT supervisors report supervising a number of groups and individuals who are in private practice. MBT has become embedded in services across several states and still other services offer MBT informed work with a team supervised by an MBT supervisor.

Mental health services providing dedicated MBT

|

State

|

Service

|

Population

|

Area Covered

|

|

WA

|

Touchstone

|

CYP

|

Perth

|

|

|

Lifespan Psychology

|

Adult & CYP

|

Perth

|

|

NSW

|

Justice Health

|

Adult female MH inmates

|

Sydney

|

|

SA

|

BPD Collective

|

Adult

|

Adelaide

|

|

VIC

|

CYMHS Alfred Health

|

CYP

|

Melbourne

|

|

|

Barwon Health

|

Adults

|

Melbourne

|

|

|

Spectrumbpd

|

Adult

|

Statewide

|

|

|

GV Mental Health Service

|

Adult and CYP

|

Goulburn Valley

|

|

Queensland

|

AMYOS*

|

CYP

|

Statewide

|

*Assertive Mobile Youth Outreach Service

The successful integration of MBT into these services suggests that clinicians and patients find something useful in it and that there is adequate training and support available for the implementation of MBT as a service delivery model at these mental health services.

Conclusions

Successful treatment of BPD with MBT is both necessary and possible as part of a strategy to address the burden of cost and suffering associated with this prevalent and disabling disorder. There is widespread recognition and evidence that providing treatments specifically developed for BPD, notably MBT, has demonstrated benefits, over and above that of TAU. With outcomes such as improved functioning, better relationships and reduction in the use of services the potential cost savings entailed in adopting treatments tailored for BPD is considerable. Because MBT is an evidence-based treatment for BPD that is already embedded in Australian services and has local capacity to train and supervise teams and clinicians across the country it has a readiness to be adopted. Incorporation of MBT as a well-recognised evidence-based treatment for BPD into the Australian mental health system would thus seem not only overdue but may be a sensible cost-benefit based decision.

References

Bateman, A., Constantinou, M.P., Fonagy, P., & Holzer, S. (2021). Eight-year prospective follow-up of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for people with borderline personality disorder. Personality disorders, 12(4), 291-299. doi:10.1037/per0000422

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2016). Mentalization based treatment for personality disorders. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hastrup, L.H., Jennum, P., Ibsen, R., Kjellberg, J., & Simonsen, E. (2019). Societal costs of Borderline Personality Disorders: a matched-controlled nationwide study of patients and spouses. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 140(5), 458-467. doi:10.1111/acps.13094

Malda-Castillo, J., Browne, C., & Perez-Algorta, G. (2019). Mentalization-based treatment and its evidence-base status: A systematic literature review. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 92(4), 465–498. doi.org/10.1111/papt.12195

National Health and Medical Research Council. (2012) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. [homepage on the internet] Canberra: NHMRC Australian Government;. Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/clinical-practice-guideline-borderline-personality-disorder

Meuldijk, D., McCarthy, A., Bourke, M.E., & Grenyer, B.F.S. (2017).The value of psychological treatment for borderline personality disorder: Systematic review and cost offset analysis of economic evaluations. PloS one, 12(3), e0171592. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171592

Vogt, K.S., & Norman, P. (2019). Is mentalization-based therapy effective in treating the symptoms of borderline personality disorder? A systematic review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92, 441–464. DOI 10.1111/papt. 12194

Disclaimer: Published on Insights in 2024. The APS aims to ensure that information published is current and accurate at the time of publication. Changes after publication may affect the accuracy of this information. Views expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the position of the APS. Readers are responsible for ascertaining the currency and completeness of information they rely on, which is particularly important for government initiatives, legislation or best-practice principles which are open to amendment. The information provided in Insights does not replace obtaining appropriate professional and/or legal advice.